Although sometimes at odds, economic efficiency and environmental justice can coexist in effective, viable climate policy. Thoughtful policy design can help ensure that environmental benefits accrue in communities that need them the most.

Climate policy has begun recognizing and prioritizing environmental justice as a central element. Whereas climate can be a core issue for environmental justice advocates, climate policy experts historically have struggled to integrate the core tenets of environmental justice into their decisionmaking processes, in part given the global nature of their objectives. Greenhouse gas emissions that accelerate global warming have an impact on everyone, but declines in air quality caused by conventional pollutants affect only those communities that are proximate to or downwind of emitters. Consequently, a potential imbalance exists in which climate policymakers share goals with environmental justice advocates, but environmental justice concerns still can be marginalized in favor of utilitarian arguments for the greater good in climate policy decisions.

This disconnect not only may undermine a potential alliance between climate policymakers and environmental justice advocates but also may hamper the effectiveness of climate policy. To be comprehensive and maximize the likelihood of reaching the stated goals, climate policy should aim to empower participants at all levels. Let’s look at how these tensions manifest in California as an example of a potential path forward.

California’s Cap-and-Trade Program

Alongside the state’s other climate initiatives, California’s cap-and-trade program, the largest carbon market in the United States, has earned California recognition as a national and global climate leader. But the program has been a point of contention for environmental justice concerns over the past decade. Initiated in 2013 for electricity and industry and expanded economy-wide in 2015, the cap-and-trade program in California focuses on reducing the state’s overall greenhouse gas emissions by employing an emissions allowance trading market.

Emissions allowance trading is a system in which emitters buy or are allocated allowances to emit greenhouse gases and can trade those allowances with each other to encourage cost-effective emissions reductions. The number of allowances that are issued is set by the state’s annual climate goals. This determination of the number sets the total emissions cap and the rate of emissions reductions across the state; this strategy does not require that any one facility reduce its emissions by a set amount. Traditionally, the geographic distribution of emissions reductions is a function of where those reductions are most cost-effective—rather than where air-quality concerns or emissions are the highest.

Environmental justice groups share the state’s ambition to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; however, they may contend that market-based mechanisms emphasize efficiency, which potentially conflicts with equity. This conflict can manifest in several ways. For instance, an inefficient and costly power plant or refinery might decrease production due to the financial influence of the carbon price, resulting in improved local air quality for nearby communities. But demand for the facility’s product could persist, potentially leading to increased utilization of another facility that might be located in a disadvantaged community. Moreover, even if a closure occurs in a disadvantaged community, facilities located upwind of those communities may increase emissions subsequently for similar reasons.

Studies that have been conducted by several institutions have explored whether disadvantaged communities have experienced net benefits from California’s cap-and-trade program (e.g., the University of Southern California, Arizona State University, the University of California, and the California Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment). The results have been mixed. While some studies indicate that disparities persisted in the early years of the program, others suggest that these disparities were reduced when considering the impacts on a longer timescale.

A lively debate has ensued around program evaluation and study methodologies, but where researchers agree is that no safeguards currently are in place to prevent future potential instances of the cap-and-trade program exacerbating environmental injustice. Emissions reductions from the program clearly are not guaranteed to occur at an equal pace in all communities, which leaves room for possible disparities.

Facility-Specific Caps on Emissions

To address the concern over the lack of safeguards, the California Environmental Justice Advisory Committee has proposed facility-specific caps on emissions. We interpret this proposal to require facilities that are located in, near, or upwind of disadvantaged communities to meet or exceed the rate of emissions reductions that occur on average throughout the state.

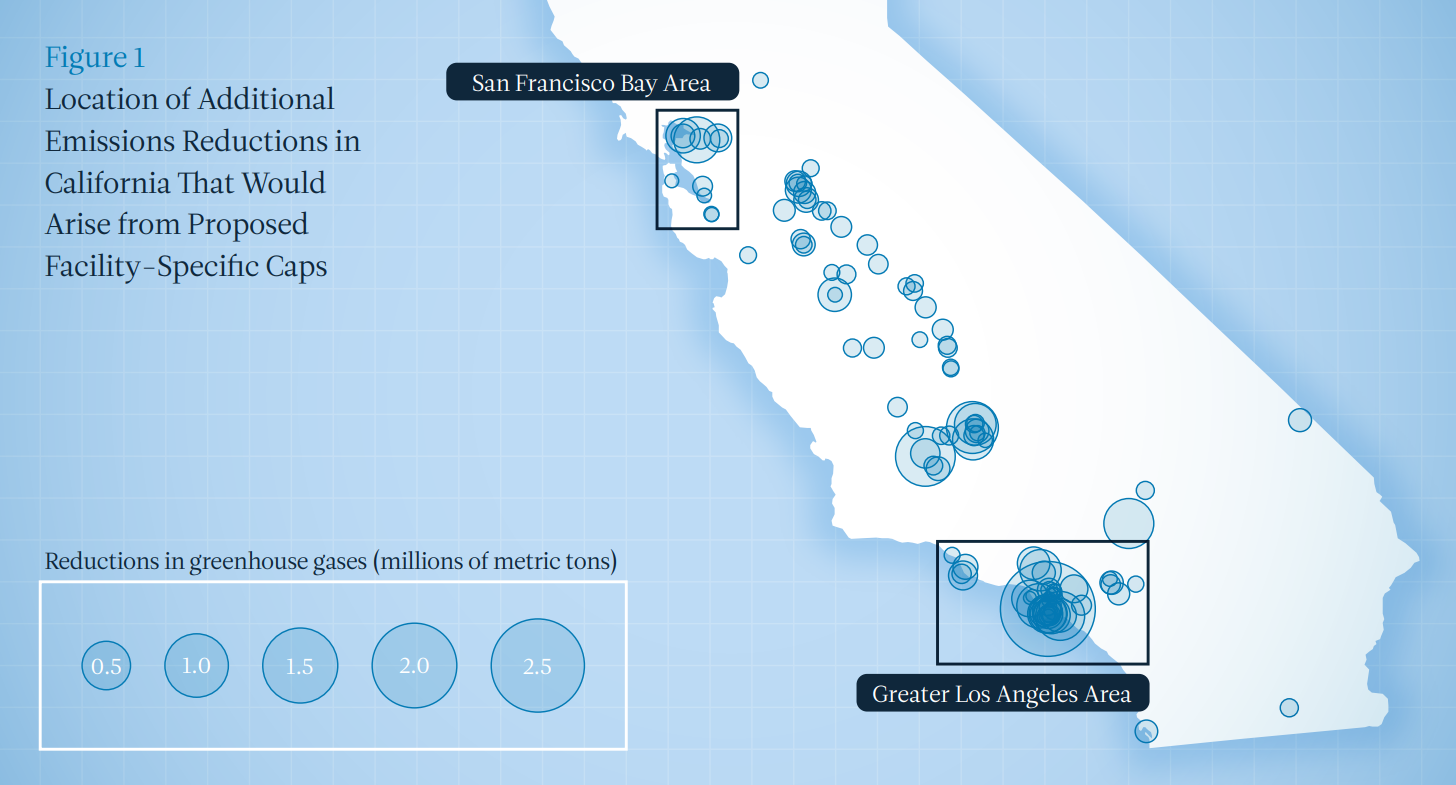

We recently published a report that evaluates the change in greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollutants in the program thus far; the report also estimates the potential impacts of the proposed facility-specific caps. To date, we find that, as a group, facilities in disadvantaged communities have reduced their emissions at a rate that exceeds the state average; however, these reductions have not occurred at all facilities. Where reductions most often lag is in densely populated areas of California (Figure 1), where communities would have benefited from the existence of facility-specific emissions caps in their vicinity.

We estimate that the proposed facility-specific caps would have a minor effect on the state’s emissions allowance trading system overall, but potentially an important effect on the small number of local communities that would experience additional emissions reductions.

California would need to adjust the supply of emissions allowances strategically to both achieve large emissions reductions in disadvantaged communities and maintain an effective emissions allowance market. We calculated this decrease in the number of allowances that California would need to impose, estimating that the change in total supply would be small (0.7 percent) and would lead to negligible price effects in the emissions allowance market.

If California regulates emissions in disadvantaged communities with facility-specific caps, the effect of the above adjustment on the market depends on whether allowance prices are off the price floor. If the price of emissions allowances is on the price floor, we would estimate that government revenues from the program would fall by 0.6 percent. But if the demand for emissions allowances is enough to keep the price of allowances above the floor, then we forecast a 3.3 percent increase in the allowance price, which would lead to a 2.5 percent increase in government revenues.

In other words, the proposed facility-specific caps would not affect the allowance market dramatically, and California’s market-based climate policy likely is robust. Where the proposal would produce a change is in disadvantaged communities where facilities have not achieved emissions reductions at a pace that matches the state average but have the potential to do so moving forward (Figure 1). Air quality would be improved by the reduction of local concentrations of criteria pollutants that are related to greenhouse gas emissions.

Fundamentally, the cap-and-trade program is not the primary regulatory mechanism that’s employed to reduce air pollution. The permitting authority of the California Air Resources Board is the primary mechanism and deserves most of the credit for improvements in air quality; comprehensive improvements need to come from this permitting authority.

Further, a high-level policy decision needs to be made about how best to balance the enforcement of facility-specific caps with efforts to maintain jobs and economic activity at facilities that are energy intensive and trade-exposed, i.e., sensitive to competition. Policymakers will have to balance various factors when implementing the details, so as to prevent perverse outcomes, some of which we discuss in our report.

Integrating Environmental Justice

Ever since making progress on its problems with smog in 1970s Los Angeles, California has led the country in environmental policy. Recent legislation in the state continues to address air quality and investment in disadvantaged communities. For example, Assembly Bill 617 in 2017 established the Community Air Protection Program to monitor and improve air quality in communities throughout the state. Senate Bill 585, passed in 2012, both identifies disadvantaged communities and designates funding for disadvantaged communities through the revenues of the cap-and-trade program. The latter bill has served as a model for federal efforts, like the Justice40 Initiative from the Biden administration and the environmental justice screening and mapping tool produced by the US Environmental Protection Agency, both of which have been adopted by other states that are looking to replicate this investment strategy.

It would not be unusual for California to include stakeholder interests that constrain economic efficiency in its ongoing decisions about policy design. When the state initiated the cap-and-trade program, a fundamental aspect of the market design was the free allocation of emissions allowances to trade exposed industries and utilities. Motivating this approach to the design of the market were concerns that industries may leave the state and a desire to shield households from the higher costs of utility services. Giving the relevant stakeholders a say in the program design was seen as important for ensuring the legitimacy, ambition, and durability of the cap-and-trade program. The same now applies to environmental justice communities, their concerns, and their recommendations for policy design.

Market-based climate policy starts with the assumption that cost-effectiveness can address the urgency of the climate crisis. The implementation process brings in other objectives that can affect and potentially constrain this cost-effectiveness. Proposals like facility-specific caps chart a path of compatibility between the objectives of climate change mitigation and environmental justice that may resemble other effective paths that have been charted with other stakeholders.

Nobel prize–winning economist Elinor Ostrom once stated that, to effectively govern the commons, all stakeholders must have a say in the process. Emissions of greenhouse gases and conventional air pollutants into the atmosphere are some of the most notorious tragedies of the commons, and all communities are stakeholders in the governance of these environmental inputs.

If California reaches its climate goals during the next decade, but with delayed air-quality improvements in disadvantaged communities, would the program be considered a success? And would the program then serve as a model for other jurisdictions, as the original legislation intended? Would the inclusion of provisions that prevent potential perverse outcomes in disadvantaged communities expand or reduce the state’s capacity to meet its climate goals?

We find that implementing the proposed policy to address environmental justice does not appear to drastically affect the allowance market. Furthermore, facility-specific caps could be a more generic way to link carbon markets without harming air quality in disadvantaged areas. By alleviating such concerns, facility-specific caps may enable or accelerate the merging of carbon markets into larger, more efficient systems. Thinking through and implementing a policy framework that can address both carbon emissions and environmental justice concerns may help California’s cap-and-trade program serve as a good model for climate policy beyond the Golden State.