The National Environmental Policy Act often takes heat for slowing down energy and infrastructure projects because of the permitting requirements it imposes. Looking at the data, we find that other factors may pose more prominent obstacles to development.

Developers of renewable energy projects in the United States have long discussed the environmental-review process as a key obstacle to wind and solar power plants reaching operation. Established in 1970 through the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), environmental review is required for major projects located on federal lands or seeking federal financial support. NEPA requires federal agencies to assess the environmental effects of major proposed federal actions prior to the execution of those actions, either through a full environmental impact statement (EIS) or the limited, concise review of an environmental assessment. In many cases, reviews can take years to complete. Court challenges claiming violations of NEPA represent another major obstacle to renewable project development.

But how much do permitting and court challenges actually affect wind and solar energy project development? And how does the pace of development differ for projects with court challenges than for projects without?

The length of NEPA review, the burden it places on renewable project developers, and other associated delays such as court challenges have been a focus of debate over the reform of federal agency review of renewable energy projects. In 2023, federal lawmakers adopted changes via the Fiscal Responsibility Act to shorten the length of NEPA review and increase the types of actions that are eligible for categorical exclusions. As a result of the recent executive order from the Trump administration that declares a national energy emergency, federal agencies are making further reductions in the length of NEPA review by limiting environmental assessments to 14 days and EIS reviews to 28 days for specific types of energy projects. Solar and wind projects are not included as eligible for expedited review. In addition, Congress continues to consider additional changes to expedite federal environmental reviews, including proposals to reduce the number of NEPA lawsuits by amending the statute of limitations.

Building on previous work involving utility-scale solar projects with a capacity of 20 megawatts or greater, we cataloged the NEPA, litigation, and operation timelines for solar and wind energy projects that completed the environmental permitting process from 2009 to 2023. Our timeline analysis focuses on outcomes for projects that underwent an EIS, as an EIS is the more challenging and complicated of the two permitting processes. Note that the solar and wind projects reviewed under NEPA account for only a small fraction of the increase in installed renewable capacity during the 2010–2023 period.

Here, we describe the results from two recently published reports.

National Environmental Policy Act: Timelines for the Review Process

Formal NEPA EIS review includes three official stages: the notice of intent, which initiates the preparation of an EIS; the publication of the final EIS, which indicates the completion of the review; and the record of decision, in which the agency approves the permit, lease, and financing decisions. The end of the review process signals that a project can move forward in its development, though if the project is located on land held by the Bureau of Land Management, it still needs final approval from the agency (which is known as a notice to proceed).

Our timelines also include initial action dates. One example of an activity that qualifies as an initial action is the date the developer submits an application for a lease, permit, or financing. Another example is the date of operation, typically when the first unit of the project begins producing power.

We find that the full NEPA review process for the solar and wind projects we evaluated—from the notice of intent to the record of decision—generally was completed more quickly than for other major infrastructure projects as reported by the Council on Environmental Quality. Compared with the reported average of 54 months, our sample shows that solar and wind projects require about 27 and 45 months, respectively.

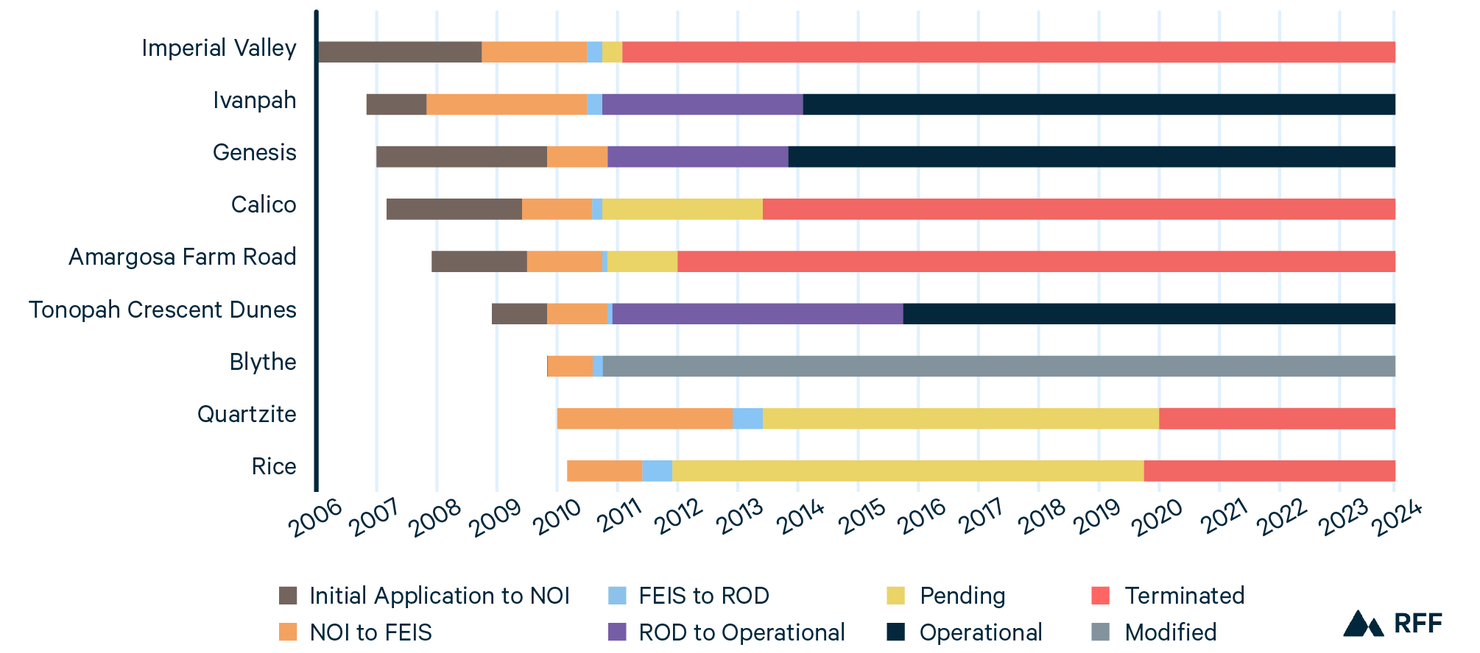

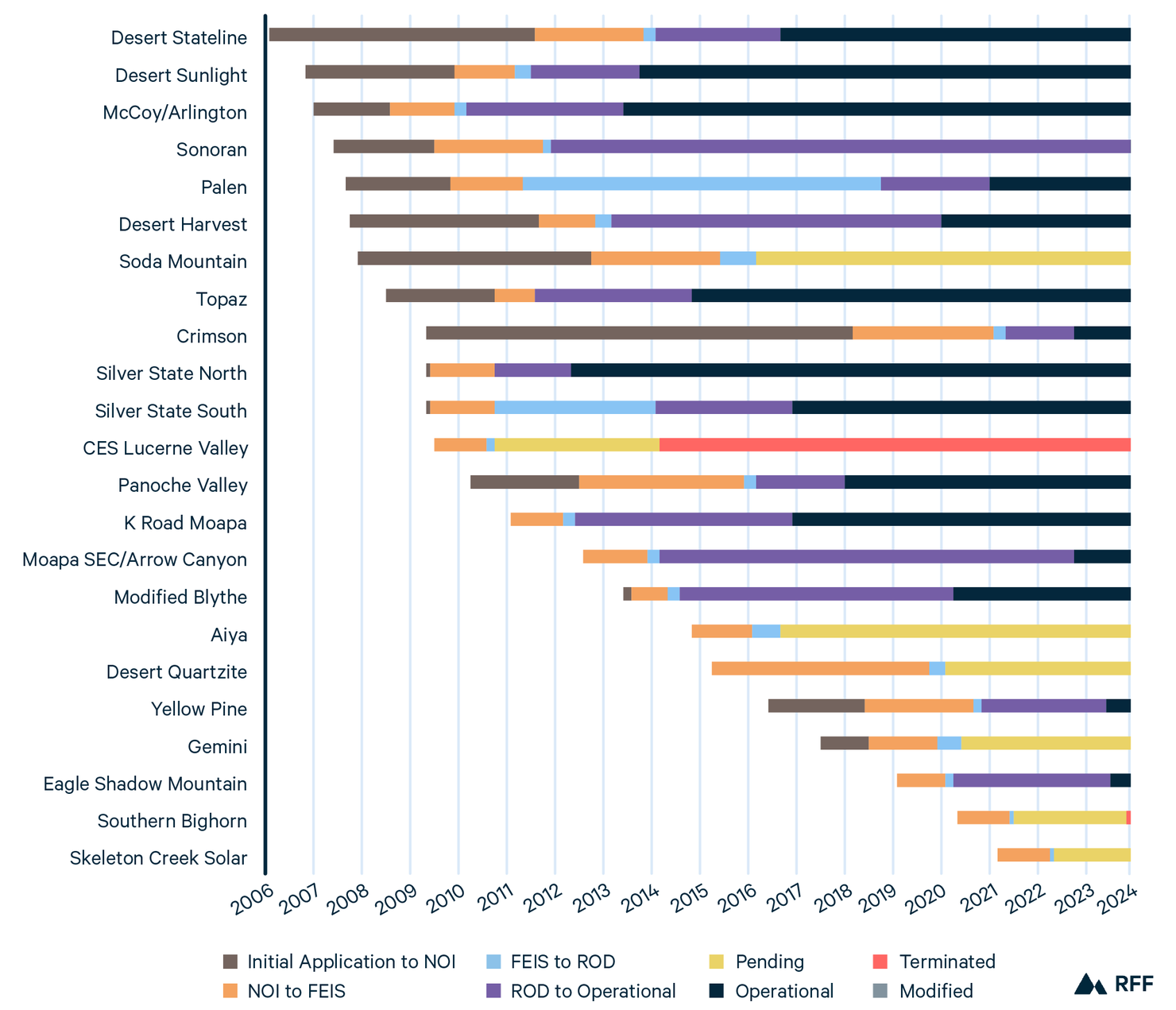

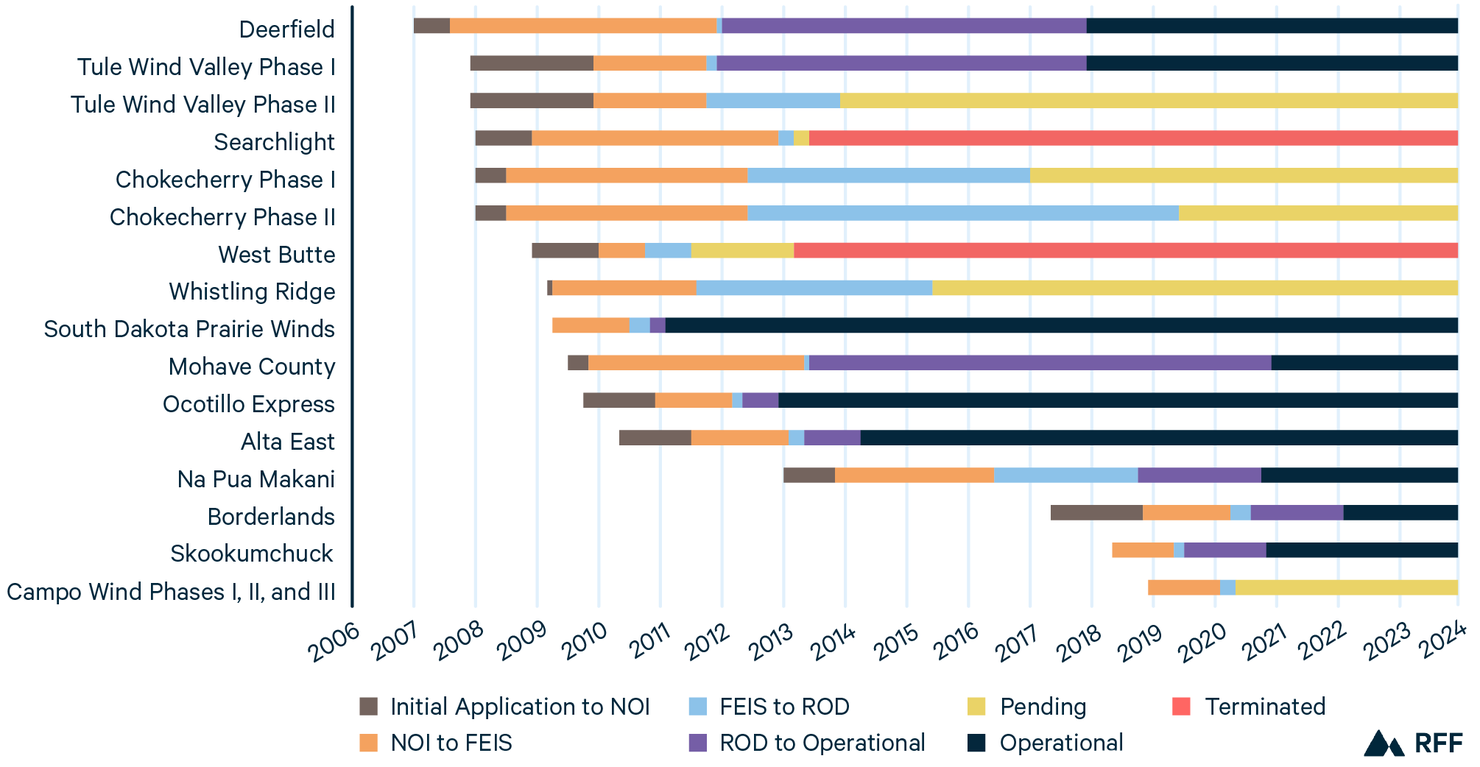

In our sample, about 60 percent of wind and solar projects completed the formal NEPA EIS process within two years (Figure 1). However, one-third of the solar projects and half of the wind projects exceeded the two-year deadline specified in the Fiscal Responsibility Act. These types of projects likely account for a disproportionate share of the policy conversation about problematic NEPA-related delays in clean energy development.

Figure 1. Timelines for Solar and Wind Energy Projects

(A) Concentrated Solar Projects

(B) Photovoltaic Solar Projects

(C) Onshore Wind Projects

Notes: NOI = notice of intent, FEIS = final environmental impact statement, ROD = record of decision.

In analyzing the time from initial action to date of operation, we observe other significant periods of delay for project developers. For the subset of 16 solar projects that completed EIS review and for which we have an initial action date, none completed construction and commenced operation within five years of the date of initial action; 4 of these projects required more than eight years to reach operational status.

For wind projects, 3 of 10 went from initial action to operation within five years; but 4 wind projects required more than eight years. For the post-NEPA review period, 11 of 24 solar projects and 6 of 14 wind projects required more than four years to complete construction and begin operation from the date that a record of decision had been issued. This delay in completing construction and beginning operation suggests that these projects encountered additional obstacles after the formal NEPA review process.

For comparison, we also looked at projects that underwent environmental assessments. The equivalent step to a record of decision in the environmental assessment process is the issuance of a finding of no significant impact after an environmental assessment has been completed. While most projects completed review with a finding of no significant impact within two years, 13 of 19 solar projects required more than one year from their initial action date, the review period established in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023.

Litigation Outcomes

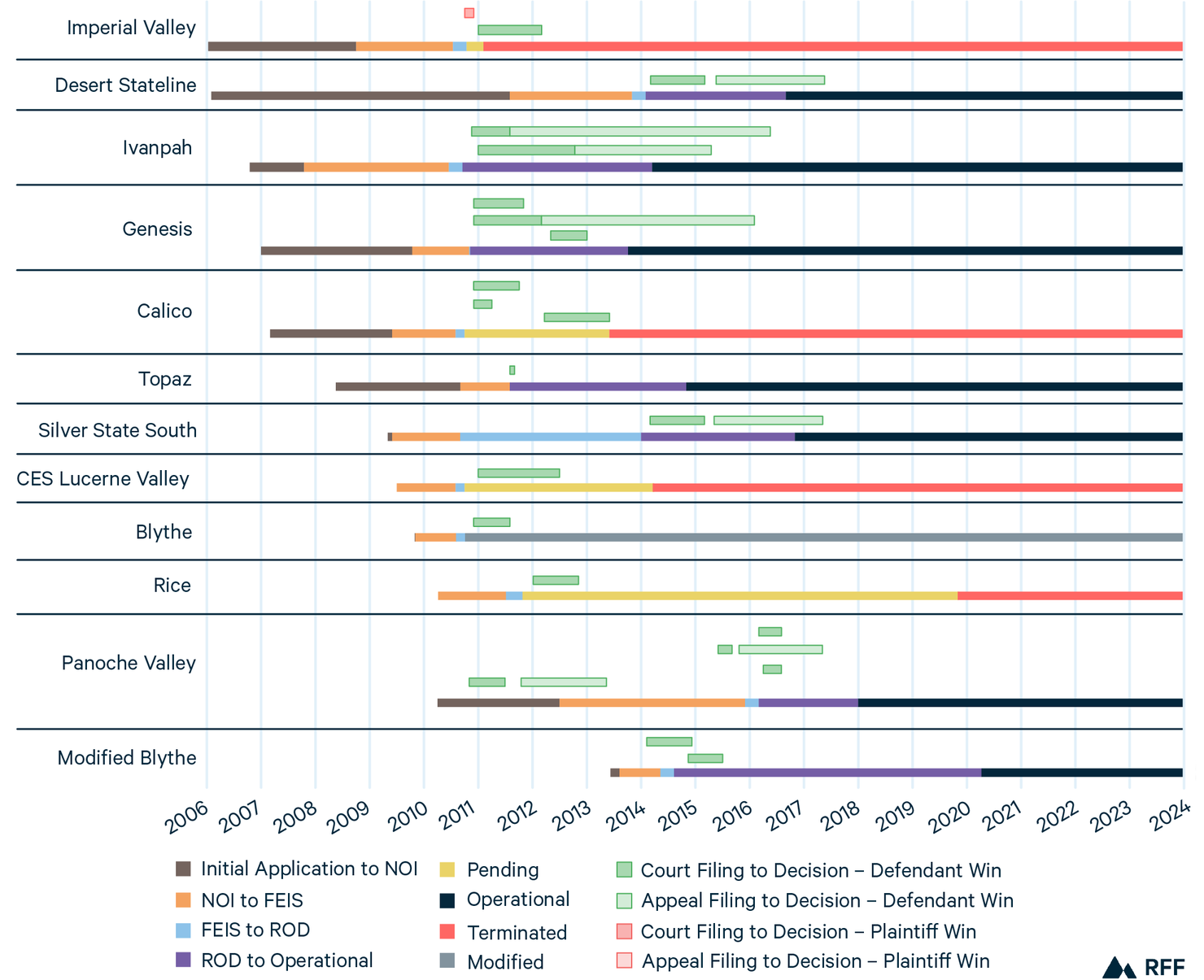

One-third of the solar projects and half of the wind projects that completed NEPA EIS review faced court challenges. In nearly every instance, court cases were filed after the government agencies had issued a record of decision. We identified court cases that raised NEPA-related concerns (or similar violations of state or local requirements) for 12 of the 32 solar projects and 8 of the 16 wind projects that completed an EIS.

Regional or local environmental groups and Tribal representatives were the primary groups initiating court challenges to solar and wind projects. National environmental groups filed court challenges for five solar projects that underwent EIS review; the defendants were permitting agencies and project developers. As the most frequent permitting agency in our sample, the Bureau of Land Management was the primary defendant for the federal cases. All the filed court challenges that contested NEPA reviews by the Bureau of Land Management addressed the Obama administration’s “fast-track” candidates, a select number of projects that had their EIS review expedited in the first years of the Obama administration.

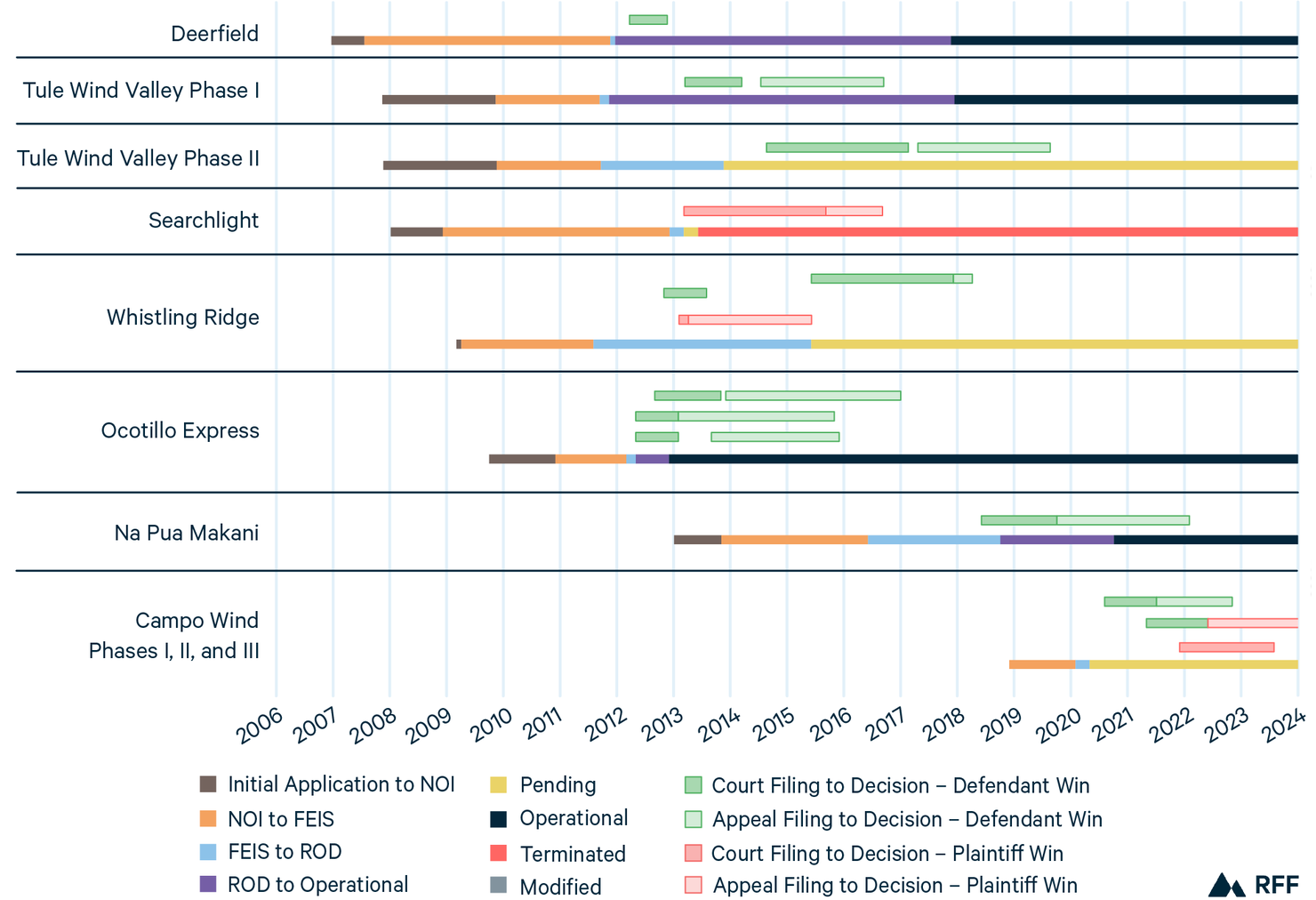

Though the defendants prevailed in most cases, court challenges caused or contributed to the termination of three projects, and six additional projects experienced significant delays as developers waited for final court decisions (Figure 2). However, a comparison of our timelines reveals that, when terminated projects are excluded, the wind and solar projects that faced court challenges had similar average project development timelines to the wind and solar projects without court challenges following the completion of NEPA review.

Figure 2. Timelines for Solar and Wind Energy Projects and Court Cases

(A) All Solar Projects

(B) Onshore Wind Projects

Notes: NOI = notice of intent, FEIS = final environmental impact statement, ROD = record of decision.

A reduction in the statute of limitations to require the filing of court challenges is one of the changes proposed in recent NEPA reform legislation. Two proposed limits are 60 days (as indicated by the Revitalizing the Economy by Simplifying Timelines and Assuring Regulatory Transparency Act) and 120 days. For 10 of the 27 cases (covering 20 energy projects) brought to federal court, plaintiffs filed their initial claim within 60 days of the date that the federal agency issued the record of decision. All but four of these cases were filed within 120 days.

Conclusion

The number of wind and solar projects that underwent NEPA review are a minority in the total US wind and solar energy portfolio. Increasing renewable energy capacity on federal lands may depend on gauging and reducing the risk that developers perceive NEPA review poses to their projects.

As Congress considers further reforms to NEPA, this discussion of development timelines offers a perspective on how NEPA reviews and associated litigation affect renewable energy projects. Our data on the timeline for the development of projects that are subject to NEPA EIS review suggests that NEPA review is just one of several factors that adversely affect project development. Financial problems faced by developers, for example, sometimes contribute to post-review delays, and projects also likely face challenges in interconnecting to the grid.

Permitting agencies also could benefit by working with developers to keep a record of the various factors that contribute to project delays. Obtaining this information also would facilitate further research into the factors beyond NEPA that hinder the construction of renewable energy projects on federal lands.