When wildfire threatens populated areas, residential impacts typically receive the most attention—but jobs are affected, too. Job growth is highest in areas of highest wildfire hazard, with six hot spots of risk for jobs and wildfire in the US West.

Just as wildfires are a major threat to homes in the US West, they also are a threat to livelihoods. While locations in the wildland-urban interface, where vegetation and housing intermingle, contain more homes than commercial establishments, growth in population and growth in industry reinforce each other. People move to high-wildfire-hazard places for the favorable trade-offs between costs and amenities. As people move to previously less-developed areas, businesses tend to follow, motivating further migration. With recent cuts to federal funding for fire prevention and firefighting in the arid West increasing the risk of more frequent and longer-burning fires (and with opportunities dwindling for communities to receive support for increasing their resilience to fires), greater consideration of threats to jobs should accompany the ongoing focus on residential impacts.

While more homes than commercial structures are typically damaged in wildfires, the financial impacts of commercial damages can be quite large. In the case of California, the state-backed insurer of last resort, the Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plan, saw a 52.6 percent increase in potential liability for commercial structures from September 2024 to March 2025, up to $40.6 billion from $26.6 billion over the six-month period. When commercial property or job sites are damaged or disrupted, the jobs dependent on them are impacted.

Wildfires affect jobs in other ways, too. For instance, wildfires can create nearby labor-market disruptions for jobs performed off-site, and economic and population growth can slow after a community has experienced a wildfire. In the recent Palisades-Eaton fires that ravaged Los Angeles in January 2025, temporary job loss was noted for in-home, service-based jobs, such as house cleaning and yard maintenance. For communities with strong economic ties to their landscapes, such as those that rely on tourism or agriculture, these disruptions can be especially costly. The impacts of the 2017 North Bay Fires on Napa and Sonoma Counties encompassed both the destruction of vineyards and a suspension of wine-country tourism.

Drawing from a report published in spring 2025, my colleagues at Resources for the Future and I looked at the coincidence of wildfire risk and jobs across 11 western US states from 1990 to 2020. We broke up the landscape into equal-sized, five-kilometer grid cells, and we categorized these areas by number of jobs and wildfire risk. To create these variables, we used data on individual businesses across the West merged with data on wildfire hazard potential, a measure of hazard developed by the US Forest Service. We classified cells into discrete wildfire-hazard categories of “very low,” “low,” “medium,” “high,” and “very high” to investigate how jobs in high- and very-high-risk areas differ from lower-risk areas and the region as a whole.

We find that areas of very high wildfire hazard have experienced the highest growth rate of any hazard category since 1990. Examining the locations of jobs in the very-high-risk category, we identify a majority in just six regional hot spots.

Distribution of Jobs in Areas of High and Very High Wildfire Hazard Across the United States

We identify 45 million jobs in 2020 across the Western states in our sample. Approximately 1.7 million of those jobs are in areas with very high wildfire hazard, double the number reported in 1990. Over the 30 years we examined, job growth in areas of very high wildfire hazard grew by 103 percent, while jobs in the West overall grew by 73 percent. This increase also demonstrates that very-high-hazard areas have claimed a slightly greater share of the region’s jobs, from 3.2 percent in 1990 to 3.7 percent in 2020.

Exposure to wildfire hazard differs across states. California has by far the most jobs in at-risk areas, accounting for 60 percent of jobs in the high- and very-high-wildfire-risk categories across the West.

Areas of high and very high wildfire hazard command a smaller proportion of wages than they do employment. Comparatively, areas of very low wildfire hazard command 5 percent more in total wages than they do in total employment. These results make sense when considering the characterization of the lowest-risk areas as urban and the highest-risk areas as more rural.

We find few differences in the distribution of job industries across hazard categories. The proportions of jobs in each sector by state appear to mirror the distribution of job industries for the US economy as a whole, with many jobs in services. For every hazard category, the most jobs in 2020 were in administration, education, health, and public services.

The Hot Spots

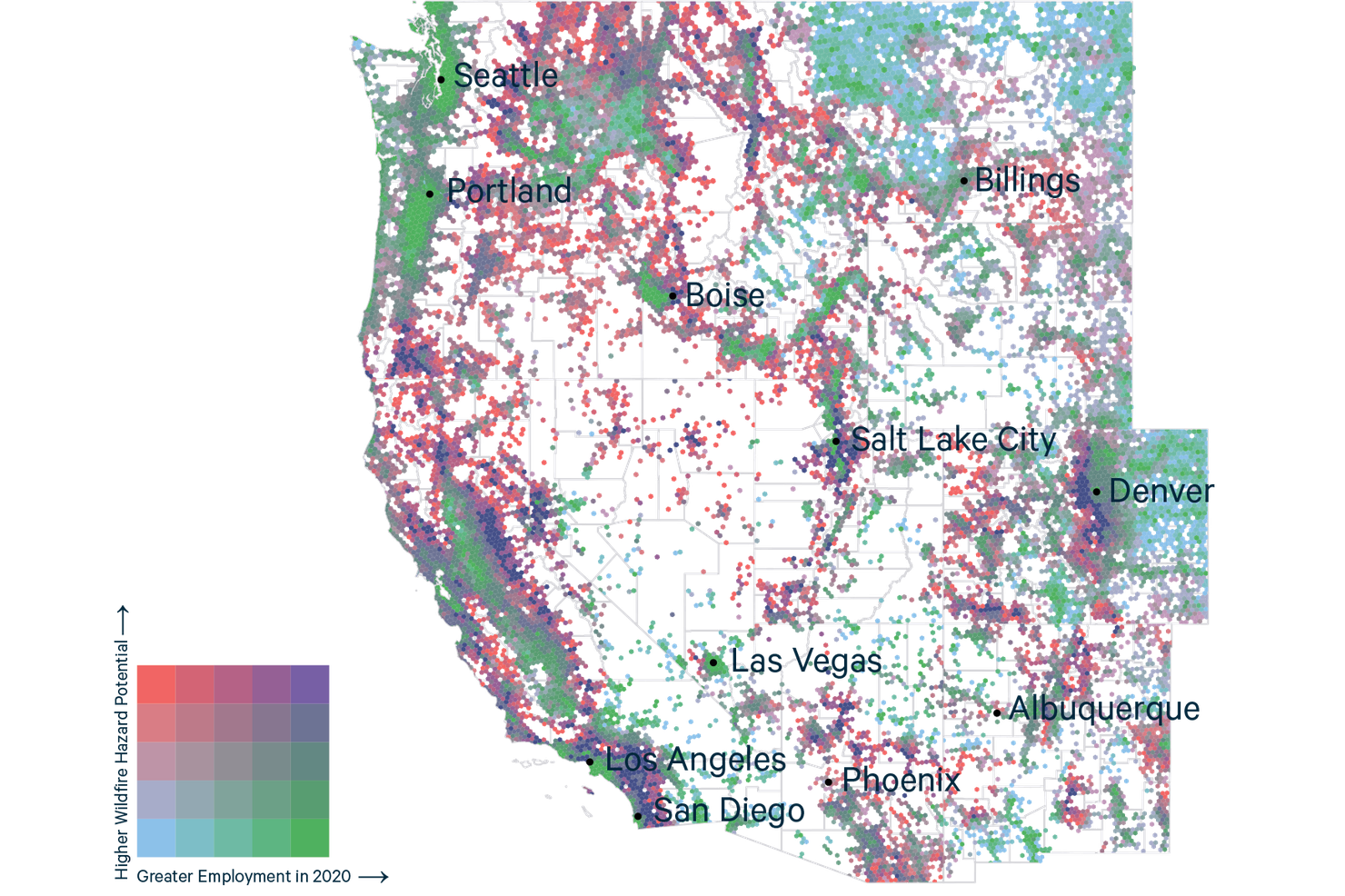

To highlight areas with many jobs and high fire hazard, Figure 1 colors each grid cell based on employment and hazard quintiles. Quintiles are bins representing a 20 percent slice of the given variable’s distribution. At the bottom left of the color legend, blue cells represent areas with the lowest 20 percent of jobs and wildfire risk (hence their concentration in places like northern Montana), while purple cells at the top right of the legend are areas with the highest 20 percent of jobs and wildfire risk. The clusters of purple cells around Los Angeles, San Diego, Salt Lake City, and Denver stand out as areas that are highly exposed to wildfire, with identifiable urban cores.

Figure 1. Overlap of Number of Jobs and Wildfire Risk Among Western US States

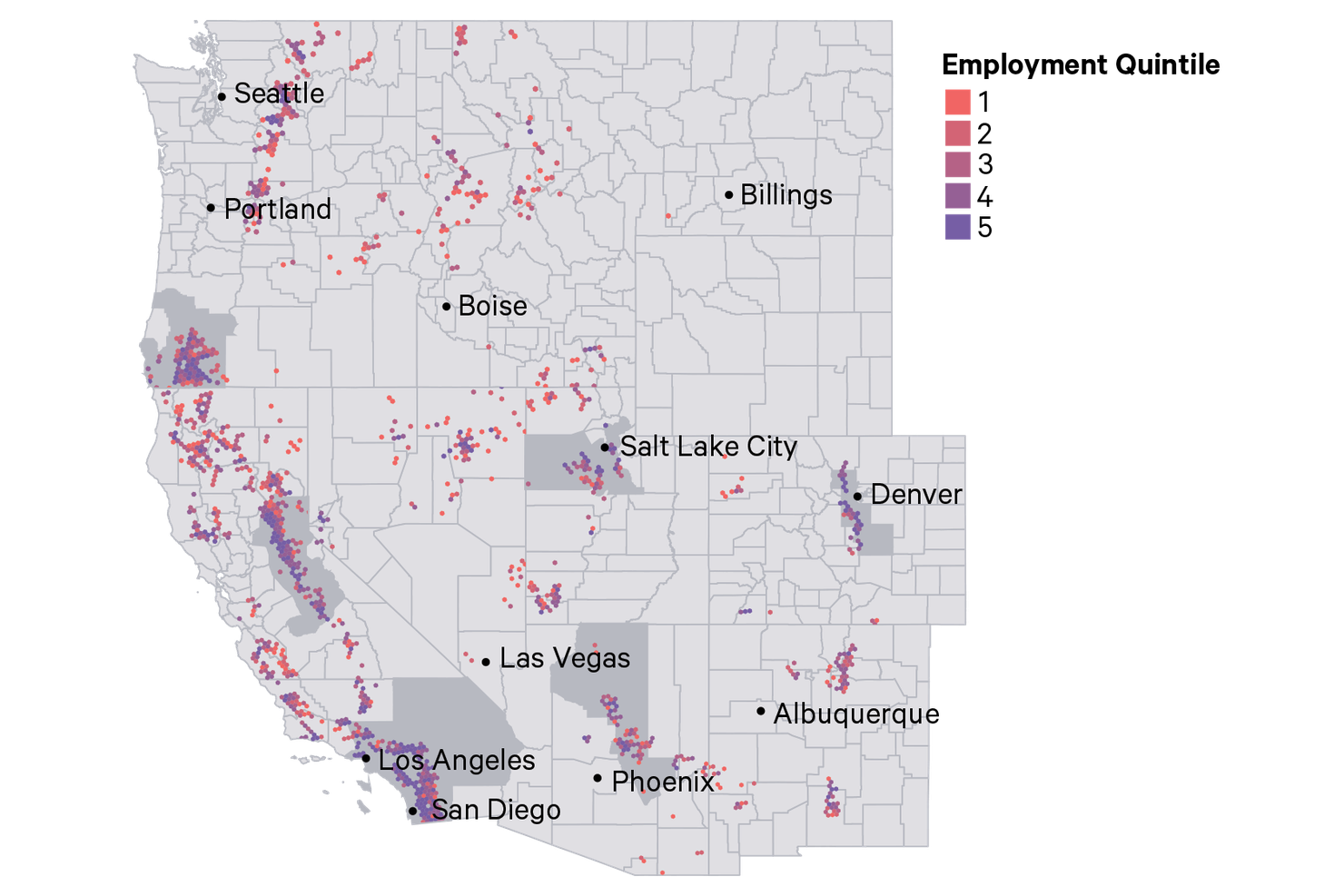

Filtering our map to only those cells with very high wildfire hazard, the resulting map in Figure 2 reveals “hot spot” areas around Los Angeles, San Diego, and Salt Lake City and three other zones not near a major city. In 2020, six regions—indicated by the adjacent counties shaded a darker gray—accounted for 85 percent of the approximately 1.7 million jobs in the very-high-hazard category. Those regions also accounted for 81 percent of the wages earned.

Figure 2. Employment Quintile Mapped on Areas of Very High Wildfire Hazard Among Western US States

So, where are most of the jobs in very-high-wildfire-hazard areas? We name the six hot spots and provide counts of their jobs in descending order:

- Southern California (1 million jobs)

- Denver-Boulder area of Colorado (117,500 jobs)

- Sierra Nevada foothills of California (94,500 jobs)

- Southern Oregon (73,000 jobs)

- Flagstaff-Globe area in Arizona (45,500 jobs)

- Central Utah near Salt Lake City (43,000 jobs)

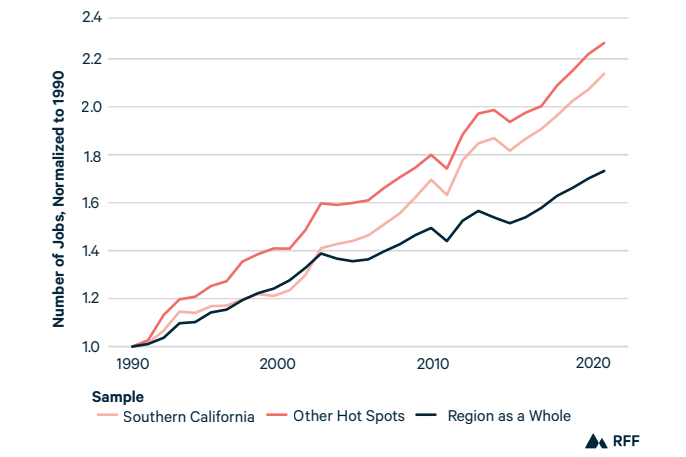

The job growth experienced in these six areas outpaces both the region as a whole and other areas of very high wildfire hazard. Compared to the overall regional job growth rate of 73 percent and the very-high-hazard growth rate of 103 percent, the number of jobs increased by 114 percent in the Southern California hot spot during the study period, and job numbers grew by 127 percent in the other five hot spots (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Employment Growth in Areas of Very High Wildfire Hazard: Hot Spots and Western Region of the United States

Although jobs in high-wildfire-hazard areas tend to have slightly lower wages than jobs elsewhere in the West, the hot spot in Southern California is an exception. Average wages are 32 percent higher there than in the other hot spots, and 45 percent higher than other areas of very high fire hazard in the West. Unquestionably, the Southern California region drives overall patterns in job and income exposure to wildfire risk in the West, a finding supported by the extreme fires the region has experienced recently, the ongoing insurance crisis, and the status of Los Angeles and San Diego as two of the most populous metropolitan areas in the United States.

Conclusions

Very-high-wildfire-hazard areas experience a higher rate of job growth than the other hazard categories, and these six hot spots drive that rate of growth, laying claim to most of the very-high-hazard jobs in 2020. But continued population expansion in the US West, and a continued predilection for locating homes and businesses in the wildland-urban interface, may portend the emergence of new hot spots in the future.

Areas like the six hot spots identified here offer favorable amenities and, at times, lower costs, but locating in those areas comes with a serious trade-off. While state and local governments can enact policies to better protect existing populations in areas with high and very high wildfire hazard, just as important may be to guide incentives toward supporting new growth and development in lower-risk areas.

Ultimately, jobs are only one in the plurality of economic risks that wildfires pose. Identifying the numbers of jobs that are subject to this risk may help to inform actions from state and local governments. However, because fires can damage local economies in multiple ways, more research into identifying the most impactful points of policy intervention, with the aim of preventing disruption or losses of both labor and capital, is necessary.