The strength of our environmental desires is of central importance to developing efficient and effective environmental policies. Over the next several weeks, we’ll be hosting a conversation that explores whether environmental desires are changing and what that means for environmental economics and policy. This is the seventh post of eleven in the series: Are We Becoming More Environmental? Reflections on Trends in Environmental Desire. This series is a result of an RFF New Frontiers Fund award for thinking creatively about pathbreaking research to advance RFF’s mission.

It seems obvious that desires and tastes change. Taste in art, food and drink, personal aesthetics (including perceptions of the “ideal” body type), and political attitudes (our nation’s view of gay marriage and the Confederate flag being recent examples) suggest that our deeper beliefs and attitudes can and do change. We’ve described a variety of theories for how and why desires change, but careful empirical evidence is scant. That’s particularly true of environmental desires and tastes. Why?

Economic Measurement

The focus of environmental economics is on the measurement of behavior and choices. People’s behavior and choices provide evidence about their preferences for one thing over another (do they prefer clean air to cheap energy, or bald eagles to land development?). Economists take this approach because it is relatively easy to get data on behavior and choices (what people buy, where they choose to live and recreate, etc.) and because the goal of most environmental economic analyses is to reveal the tradeoffs associated with those behaviors and choices as a guide to public policy.

Data on our deeper desires are much harder to come by and, as noted earlier, preferences and behavior can change without a change in underlying desires. In other words, even if people behave differently or make different choices over time (i.e., have changing preferences) that does not necessarily mean their underlying desires are changing. Choices and behavior can change simply because the costs of supplying environmental goods change. We spend more time in parks when they are located closer to us (making it cheaper to enjoy them). We buy cleaner products when innovators figure out how to produce them more cheaply. Our demand for another acre of parkland increases as the abundance of total parkland decreases. Our demand for clean water will fall as water treatment technologies improve and provide a cheaper substitute (i.e., treated water).

If our more fundamental ethical beliefs, attitudes, and aesthetic desires change, our demand for environmental goods will also change. However, changes in desire must be detected and predicted as a category distinct from changes in supply, scarcity, and substitutes.

One explanation for the lack of empirical study of “taste change” within economics is the difficulty of isolating taste change from other factors affecting preferences. Studies must employ methods and data to control for changes over time in supply, scarcity, and substitutes. Illustrative exceptions that prove the rule are studies of changing food consumption patterns. For example, economists have empirically explored changes in US beef consumption and tried to isolate the effect of changes in the “taste for beef” from other factors affecting consumption such as prices, household income, and demographic change. When these latter factors are controlled for, the residual change in consumption can be attributed to a change in taste (in this case, perhaps arising from changed attitudes toward health).

Could environmental economists conduct analogous studies to detect environmental taste changes? In principle, yes. In practice, data limitations currently make it nearly impossible. Taste change studies of market commodities such as beef can make use of a variety of data on prices and consumption. These data are collected consistently at regular intervals over time (allowing for time-series analysis). Such data is relatively abundant because the goods in question are market goods and markets generate a great deal of routinely collected information on prices and consumption. Environmental goods and services, however, are usually not market goods and thus lack price and consumption data. To be sure, environmental economists spend much of their time deriving “virtual prices” and gathering data on environmental consumption related to things such as recreational activity. But environmental goods lack the routine, consistent collection of data associated with market commodities. As a consequence, environmental economics has to date produced few, if any, studies of how virtual environmental prices or consumption change over time—let alone analyses designed to isolate taste change from supply, scarcity, and substitutes.

One way to move forward (which, to our knowledge, has not been attempted) is to create and repeatedly administer over time a national or global environmental preference survey designed to detect environmental taste change. Any such study would require a long-term financial and institutional commitment. It would also require a design that reflects best practice stated preference methods, which are used to get around the “missing prices” problem associated with nonmarket environmental goods. They involve the construction of realistic, plausible decision scenarios that ask respondents to make (simulated) choices. By comparing people’s choices between nonmarket environmental goods and money or goods with a known market value, the value or preference for environmental goods can be inferred (for example, would you rather have a new park or a lower property tax bill?). To be clear, such an endeavor would involve more than simply conducting repeated experiments since, as noted earlier, detection of taste change requires careful attention to confounding factors, such as changes in supply, scarcity, and the availability of substitutes.

Another approach would be to examine how environmental desires vary cross-sectionally in response to different conditions. For example, research has been undertaken in experimental economics to examine cross-country differences in variables such as trust and reciprocity. These studies have participants play economic games designed to examine certain types of behavior and compare how outcomes differ around the world. We could imagine something similar being done to compare environmental desires in different countries. Although it would be challenging to isolate the factors that are the underlying cause for differences, useful patterns could emerge showing correlations between variables such as income, education, or various institutional structures and environmental desires.

Opinion Polls

Forget about complicated economic methods, can’t we just look at opinion polls to tell us about our changing environmental attitudes? Not really. Although opinion polling has its uses (e.g., predicting near term voting patterns), it does a poor job of revealing our underlying beliefs, desires, and attitudes and how they change over time.

To begin with, it’s rare for environmental polls to be conducted consistently over long periods of time, which makes it hard to see changes. Gallup polls are one exception; several extend back to the 1970s and 1980s (almost no environmental polling existed prior to that time).

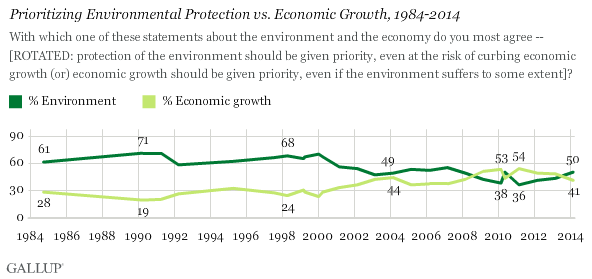

Since 1984, Gallup has been asking Americans about whether they place higher priority on economic growth or environmental protection. The results and precise wording of the question are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Prioritizing Environmental Protection vs. Economic Growth, 1984–2014

Through the 1980s and 1990s a significant majority of respondents favor environmental protection. Beginning around 2000, the gap narrows and, in fact, between 2009 and 2013 a majority prefers economic growth. Does this imply that Americans’ environmental preferences are weakening? No, for at least two reasons.

First, legislation, regulation, and investment in environmental protection expanded significantly over the 30-year period. In the 1980s, the major environmental laws in the United States were just beginning to be implemented, following a surge of legislation and regulatory change beginning in the 1970s. In other words, baseline “environmental protection” increased over the period. With status quo levels of environmental protection getting stronger, it’s not surprising for people to give additional environmental protections a lower priority over time. Rather than evidence of weaker environmental desires, the numbers may just reflect the increased satisfaction of our desires over those 30 years.

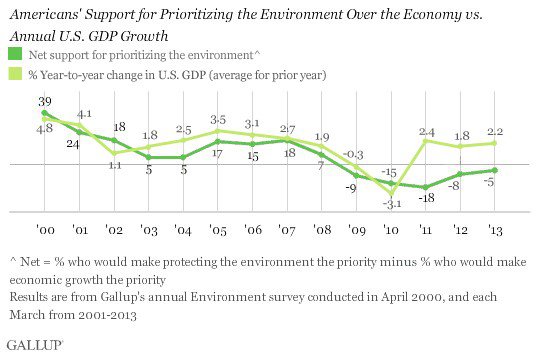

Second, the numbers may simply reflect that people’s relative desire for economic growth increases when economic growth falls. Consider Figure 2, which relates Figure 1 (now expressed as “net support for prioritizing the environment”) to changes in US GDP. The correlation suggests that what’s changing over the period is our desire for economic growth, not our environmental desires.

Figure 2. Americans’ Support for Prioritizing the Environment over the Economy vs. Annual US GDP Growth

Wealth and Our Environmental Desires

Wealth and income affect our environmental behavior and choices. Environmental quality is thought by many economists to be a “luxury good,” such as diamonds and fine wine, where demand increases more than proportionally with income. Wealth effects are therefore important if we are to predict future environmental preferences. But a distinction can be drawn between wealth-driven changes in demand and underlying attitude-driven changes in demand. Put another way, if we control for changes in wealth—and scarcity and substitutes, etc. —it is possible that our demand for environmental goods will change over time due to other adjustments in our psychology, ethics, and aesthetic tastes.

Having said that, there may be important connections between wealth and psychology, attitudes, and ethics. Consider some speculations:

Research indicates a positive correlation between wealth (above some base level of subsistence) and depression and anxiety. Other research indicates that outdoor experiences help relieve depression and anxiety. Might wealth lead people to “self-medicate” via outdoor experiences in a way that strengthens psychological demand for nature? Wealth also tends to lead to higher educational attainment, which may in turn increase various forms of environmental knowledge in a way that strengthens certain environmental attitudes.

The effect of wealth on empathy, honesty, and altruism is also a subject of social science research. For example, research has found a negative relationship between wealth and pro-social behaviors and attitudes. Does that bode ill for environmentalism, which to be effective often requires a collective ethic?

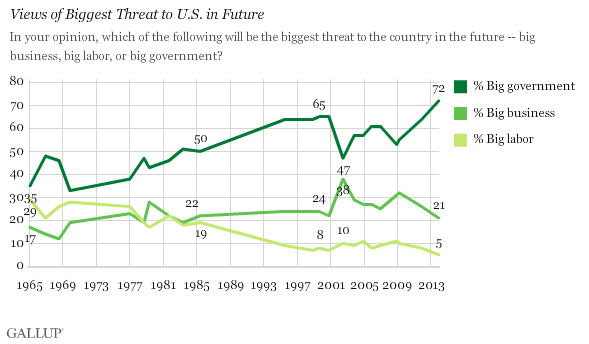

Another issue with the Gallup polling (which we pick on only because there are so few other examples) is its reliance on the term “environmental protection.” The term is vague and thus subject to various interpretations by respondents and readers alike. Our guess is that many respondents reasonably equate “environmental protection” with “environmental regulation by the federal government.” If so, the survey may conflate attitudes toward the environment with attitudes toward government. Figure 3 shows why that matters to interpretation of the poll.

Figure 3. Views of Biggest Threat to US in Future

Since 1965, distrust in “big government” (itself a vague term) has grown significantly. This is yet another potential explanation for the decadal decline in the environment versus growth priority ranking.

Another poll, this one from ABC News, tracked respondents’ self-identification as an “environmentalist”, finding a significant decline between 1984 and 2008.

Again, though, does this really signal a weakening of pro-environment attitudes, or is something else going on? The website thesaurus.com suggests the following synonyms for “environmentalist:” “conservationist,” “naturalist,” “preservationist,” and “ecologist.” But it also lists a more pejorative set, including “greenie,” “tree hugger,” and even “eagle freak.” Clearly, the term has some baggage, having to it a whiff of hippie, free-loving liberalism. So if you’re not a hippie, free-loving liberal, you may not want to label yourself that way—even if you care a lot about the environment. Thus, the poll may say more about the semantic evolution of a single word than it does about attitudes toward nature.

In fact, viewing the polls together, it is remarkable how strong the preference for environmental protection (Figure 1) remains given the countervailing trends: the improvements over time in baseline environmental protection, dips in economic growth, increased distrust in government, and growing distaste for the label “environmentalist.” Given those headwinds, we can conclude that our underlying environmental attitudes have grown stronger over the last 30 years, rather than weaker.

Up next in the series: How to Evaluate Policies that Change Our Desires.

Read previous posts in this RFF blog series: Are We Becoming More Environmental? Reflections on Trends in Environmental Desire.

1. Are We Becoming More Environmental? An Introduction

2. Growing Environmentalism: The Difference between Desires, Behavior, and Preferences

3. What Changes Our Environmental Desires? A Look at Taste Formation

4. What Changes Our Environmental Desires? Experience and Learning Matter

5. What Changes our Environmental Desires? The Impacts of Social Norms.