New research finds that disclosing wildfire risks to potential homebuyers in California reduces sale prices.

Damages from wildfires in the United States are on the rise. Of the top 10 costliest wildfires in terms of insured losses, eight have occurred since 2017. One reason for the rising costs of wildfires is the growing number of people and property in harm’s way. The wildland-urban interface, where the built environment meets or intermingles with areas of wildland vegetation—including areas with high potential for fire hazards—is by some accounts the fastest-growing land area in the United States.

Whether people fully understand the risk of wildfire when choosing to live in the wildland-urban interface is an open question. If they do understand, housing prices should reflect that risk; houses in locations where the risk of wildfire is higher should sell for less, all else being equal. However, these houses may not sell for less if homebuyers don’t fully understand the risk of wildfire. This potential gap in understanding offers a strong argument for the disclosure of wildfire risk to homebuyers. Disclosure could enable homebuyers to make more informed decisions when purchasing a house.

Regulating the Disclosure of Wildfire Risk

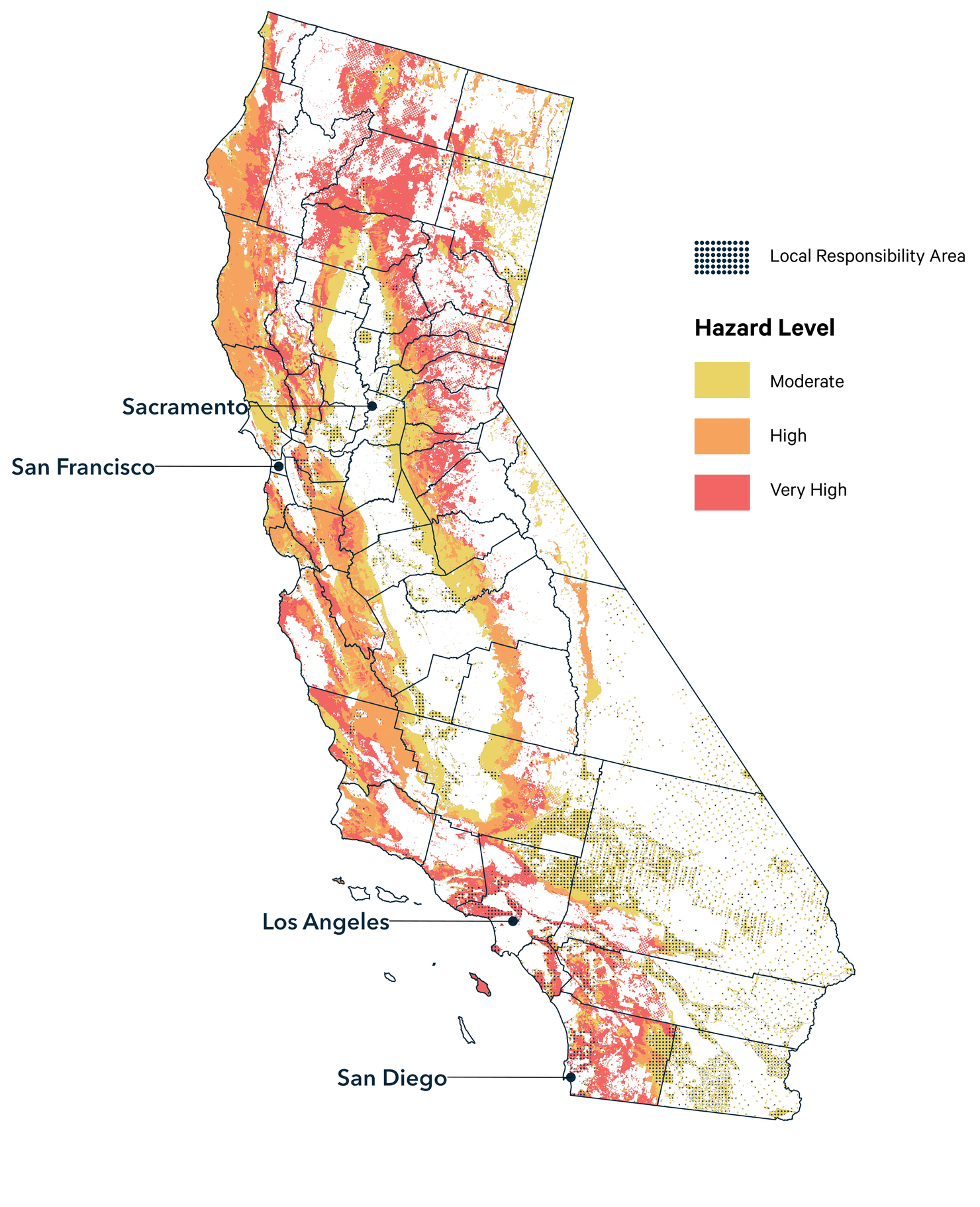

California is one of only two states (along with Oregon) that require a house seller to disclose the risk of wildfire. In California, disclosure depends on the hazard level (moderate, high, or very high) that is assigned to a house by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and the local, state, or federal jurisdiction responsible for preventing and suppressing fires. In so-called State Responsibility Areas, the disclosure of wildfire risk is required if a house’s hazard level is moderate or higher. In so-called Local Responsibility Areas, disclosure is required only if a house’s hazard level is very high. A large area of very high hazard exists in the northern part of California that is east and north of the Sacramento Valley, but areas of very high hazard exist in other parts of the state, as well (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of Wildfire Risk in California, by Hazard Level

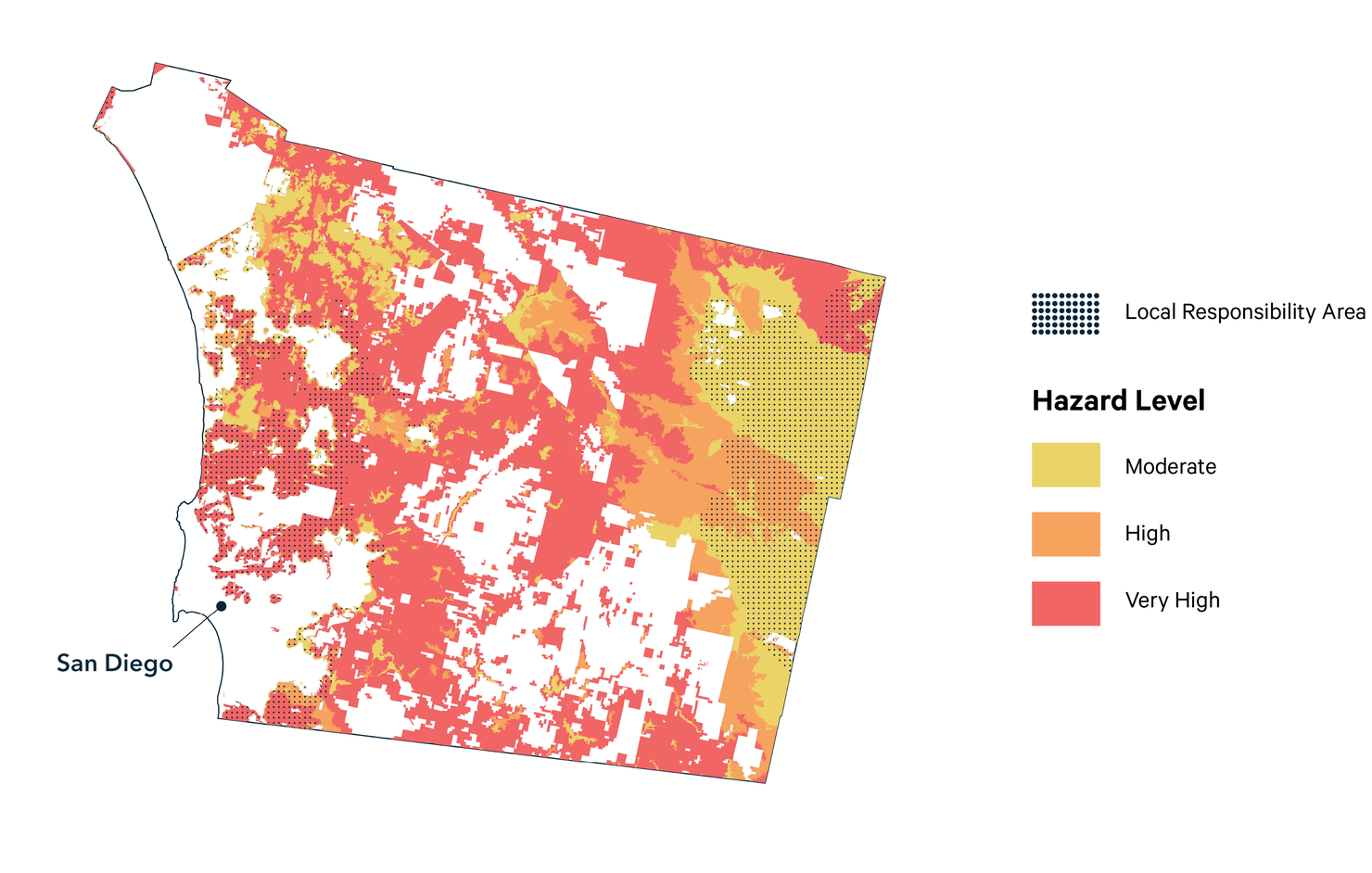

Very high hazard areas exist in various parts of California. The map of San Diego County in Figure 2 illustrates geographic variation in terms of hazard levels and state or local responsibility. In Figures 1 and 2, all areas that are not colored represent either areas with a low level of wildfire hazard or land for which the federal government is responsible.

Figure 2. Distribution of Wildfire Risk in San Diego County, California, by Hazard Level

Disclosure of Wildfire Risk Decreases House Prices in California

In a recent working paper, we set out to analyze how California’s disclosure requirements affect housing prices. We used data on property sales for single-family homes from January 2015 to March 2022; we obtained these data through the Zillow Transaction and Assessment Database.

Because wildfire risk is highly correlated with amenities that contribute to the value of a house, such as scenic views and access to outdoor recreation areas, separately identifying the market effects of amenities from the effects of risk can be difficult. To address this challenge, we compared sales data from both sides of boundaries between areas that have different disclosure requirements. Though these requirements can change abruptly at a boundary, the amenities that correlate with the risk of wildfire should vary continuously. We compared the sale prices of houses that are close to a boundary, and in the same hazard level, but which have different disclosure requirements.

In our analysis, we also accounted for property characteristics (such as the size of a house) and neighborhood characteristics (such as the distance to protected public lands). Through this approach, we isolated the effects of wildfire risk disclosure on the sale prices of otherwise similar properties.

We find that the disclosure of wildfire risk decreases the sale price of a single-family home by an average of 4.3 percent. This difference in sale price equates to a $23,700 reduction in the willingness of homebuyers to pay for high-hazard homes, considering that the median sale price of houses in our sample that are near a boundary is $557,000. Our results are driven by sales in Southern California, where the negative effect of disclosure is as high as 6 percent. Additionally, the magnitude of the price discount increased in 2020 and 2021; these years followed a period of large, high-damage fires.

What’s Ahead for Disclosing Wildfire Risk in the Housing Market

Our results suggest that disclosure matters to homebuyers and that, without disclosure, homebuyers do not fully incorporate the risk of wildfire into their decision to purchase a house. The results also lend credence to efforts to increase disclosure about all kinds of natural hazards. Even though the Federal Emergency Management Agency has mapped flood risk for a long time, the disclosure of flood risk, including maps of flood risk and whether a home has flooded previously, varies widely across states.

First Street Foundation recently has developed risk factors for both flood and fire at the level of individual properties across the United States, and this information has been incorporated into listings that are managed by the real estate websites Redfin and Realtor.com. Whether these risk factors will be a valuable tool for circulating information about risk remains to be seen. Risk information that is communicated through listings also may not be as salient as an official disclosure—and, without disclosure requirements, realtors may opt to withhold risk information from prospective buyers.

Risks also can be reflected in the price of insurance. Protection from fire damage is provided through homeowners insurance; because many different factors affect insurance premiums, homeowners may not easily understand how wildfire risk specifically contributes to premium costs. This complexity means that communicating the risk of wildfire through the insurance market may be less transparent than disclosure that occurs during property sales. As western states like Colorado grapple with the impacts of wildfires, California’s disclosure laws have been viewed as a guide for how to ensure that buyers are aware of risk. Our findings offer support for following California’s lead.

One acknowledgment is that, although we examined the short-term effect of risk disclosure on housing prices, disclosure also may have long-term effects that not only could change who chooses to live in risky areas, but also whether any housing at all is developed in those areas. This question deserves more research.

Ultimately, reducing exposure to wildfire risk will take a multipronged approach that includes disclosure requirements, risk-based insurance premiums, and the effective use of local land and policies that mitigate wildfire.