Trucks are a challenge to decarbonize, though policy shifts and new technologies could speed the deployment of a lower-carbon fleet.

Trucks account for a large and growing share of US greenhouse gases (GHG), second only to passenger vehicles as a source of transportation emissions. Promising technologies—such as cheaper batteries and automated driving—could help, and policymakers are increasingly focusing on other strategies to reduce truck emissions, too. Last year, for example, California introduced legislation that requires manufacturers to transition from diesel to zero-emissions trucks and vans. The Biden administration has signaled interest in electric vehicle infrastructure, and the GREEN Act of 2021 includes a tax credit for zero-emissions heavy-duty trucks and buses.

So, it may come as a surprise that the transition to a cleaner truck fleet seems quite far off, compared with the transition to clean passenger vehicles. Largely because of up-front costs, market penetration of electric and fuel cell long-haul trucks is expected to remain trivial through at least 2030. But there may be reason for optimism: when the transition begins, the impact on trucks will be swift.

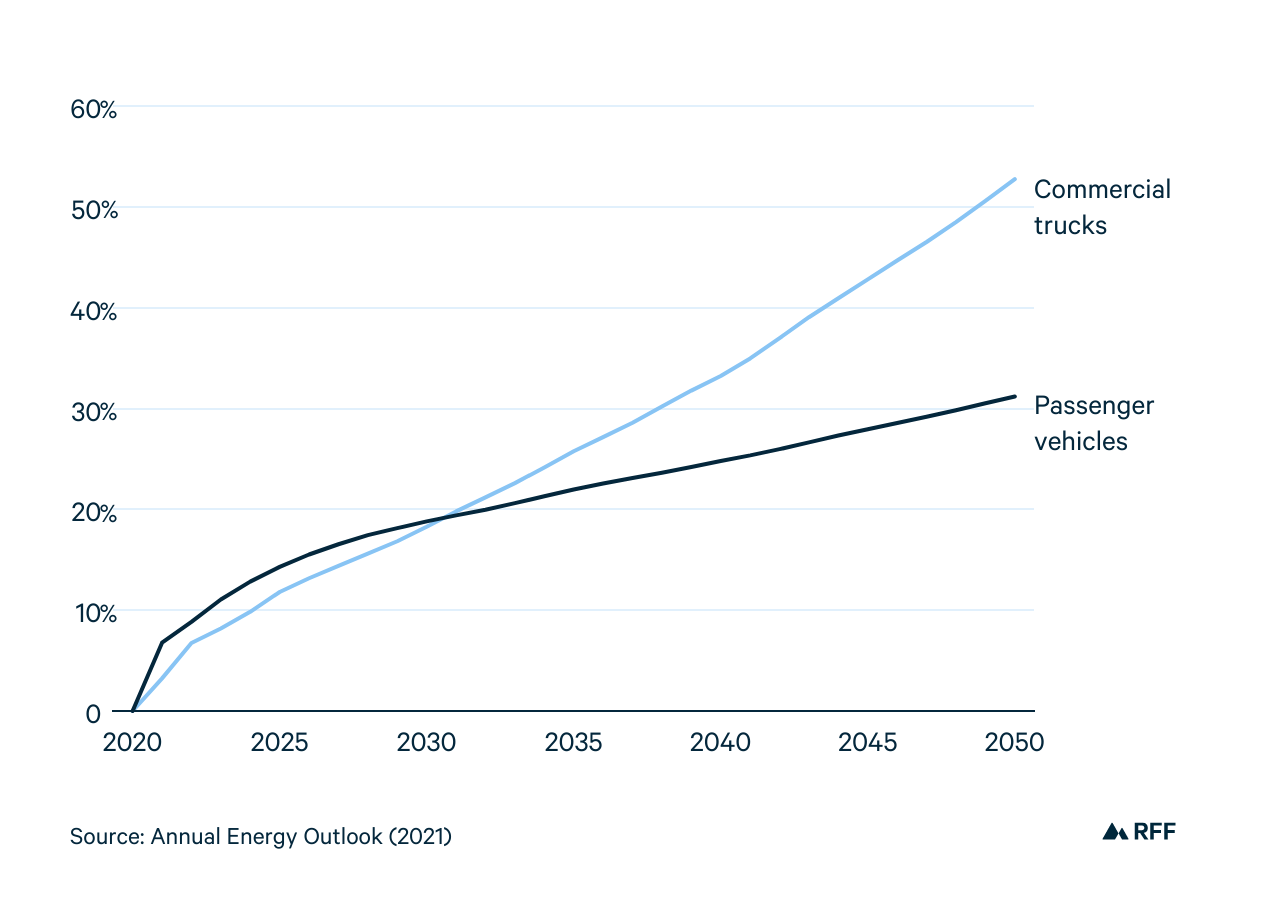

When it comes to setting and achieving climate goals, most of us are much more familiar with the role that passenger vehicles will play than we are with the ways that medium- and heavy-duty trucks will contribute. A useful starting point is to compare the GHG emissions of these vehicles. According to the US Energy Information Administration’s Annual Energy Outlook 2021, passenger vehicles will account for about 55 percent of carbon dioxide emissions from the transportation sector this year, and trucks will account for about 25 percent. (These trucks include anything from a large pickup truck to a long-haul truck, as well as buses and other “vocational” vehicles.) Over the next 30 years, trends for the two types of vehicles will diverge to an extent (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Projected Carbon Dioxide Emissions for Passenger Vehicles and Commercial Trucks

For both types of vehicles, emissions are expected to increase over the first few years, during a post-COVID “recovery” period for vehicle travel. Then, emissions start declining, but by the late 2030s, emissions from trucks are expected to start increasing again, while emissions from passenger vehicles will remain flat. Comparing emissions in 2020 solely to expected emissions in 2050, passenger vehicle emissions will decline modestly, while truck emissions actually will increase modestly.

Broadly speaking, policies affecting GHG emissions from trucks are similar to those for cars. The US Environmental Protection Agency and the US Department of Transportation administer GHG and fuel consumption standards for trucks, which are analogous to the Corporate Average Fuel Economy program for passenger vehicles. Currently, the truck standards tighten steadily through 2027, though the Biden administration is likely to make these standards even more ambitious.

At the same time, vehicle miles traveled for both passenger vehicles and trucks will continue growing steadily through 2050 (Figure 2), but miles traveled by trucks will grow about twice as much as miles traveled by passenger vehicles. This extra growth explains much of the differing emissions paths in Figure 1, because more driving necessarily entails higher emissions.

Figure 2. Projected Growth for Miles Traveled for Passenger Vehicles and Commercial Trucks

Fewer federal subsidies exist for new plug-in electric and fuel cell trucks and buses than for their light-duty counterparts, although a federal weight-based tax credit applies for medium- and heavy-duty fuel cell vehicles, along with an alternative fuel tax exemption for school and city buses. The GREEN Act seeks to change this system by providing a tax credit for zero-emissions trucks and buses equal to 10 percent of their sale price; other proposals are circulating in Congress that have similar aims.

In a prior blog post, I observed that consumers do not appear ready to start buying plug-in electric vehicles en masse. If anything, the situation is more discouraging for trucks. Although gasoline and diesel fuel efficiency is likely to continue improving incrementally over the next decade (a few percent per year), most analysts expect limited penetration of electric and fuel cell trucks through at least 2030. To be sure, some promising news has arisen for government truck fleets: President Biden issued an executive order to electrify the federal fleet, and Maryland’s Montgomery County announced plans to replace diesel-powered school buses with electric ones. But the bigger challenge is that long-haul trucks account for the bulk of emissions from medium- and heavy-duty trucks.

The situation for trucks is not all doom and gloom, however. Automated driving may help reduce fuel consumption and emissions, which could be particularly important if the electrification of the truck fleet takes a long time. Although truck drivers are highly skilled and often are incentivized to reduce fuel consumption, automation could further reduce fuel consumption—possibly by as much as 10 percent.

Another reason for optimism is that long-haul trucks turn over much more quickly than passenger vehicles. Long-haul trucks account for the majority of fuel consumption among all commercial trucks. They may be driven more than one million miles over their lifetimes, with most of those miles driven in the first four to five years of the truck’s life. In other words, when you see a long-haul tractor-trailer on the highway, the tractor is probably less than five years old. In contrast, the typical passenger vehicle on the highway is 10–15 years old. So, if electric or fuel cell long-haul trucks become competitive with trucks that run on diesel fuel, we could quickly see a lot more of those trucks on the road.

Obviously, this story omits some complexities, such as infrastructure requirements and the fact that some long-haul trucks are still used heavily as they age. Some recent articles have bemoaned a slow transition to a cleaner passenger vehicle fleet, but a rapid transition to much cleaner long-haul trucks remains possible. A strong policy commitment to promoting innovation and facilitating new infrastructure certainly will aid in that transition.

This article also appears on the University of Maryland’s Transportation Economics and Policy Blog, which is supported in part by funding through the Maryland Transportation Institute.