If the endangerment finding structurally hampers US climate policy, Then the impacts will reverberate through global climate policy.

The second Trump administration announced the United States’ second withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on January 20, 2025, the first day of the new administration. Six months later, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a recommendation to rescind the “endangerment finding”—a result of a 2007 Supreme Court case—which argued that greenhouse gases pose a threat to public health and welfare in the United States and therefore are subject to direct regulation by EPA under the Clean Air Act.

These two actions, though playing out on different political stages, are connected in more ways than meet the eye.

For international climate policy—where the Paris Agreement remains the primary framework to structure international cooperation—actions taken in one country can send a signal to other countries and thereby affect global climate policy momentum. This is the underlying logic of the process in which all parties to the Paris Agreement submit pledges, called nationally determined contributions, or NDCs, to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) every five years. The pledges are then collectively assessed by all parties to the Paris Agreement and updated every five years.

The immediate magnitude of the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement (which formally takes effect in January 2026) can be measured by the country’s substantial share of global emissions. But even US domestic policy is more influential globally than its proportional contributions to emissions. The endangerment finding underpins several US federal regulations targeting greenhouse gas emissions; for example, EPA standards regulating power plant carbon pollution and the fuel economy of passenger cars. Without the endangerment finding, the legal basis for these climate policies disappears.

By eliminating a legal foundation for US domestic policy, the United States is inviting other nations to revisit their own internal policies. Indeed, Energy Secretary Chris Wright, in an editorial for the Economist, referred to the previous administration’s climate policies as “a regulatory assault aimed at eliminating hydrocarbons” while inviting other countries to mirror the United States and prioritize “energy addition, not subtraction.”

The United States is therefore no longer just critical of international climate policy agreements, but also increasingly of climate action more broadly. These changing attitudes may be influencing other countries to reconsider their Paris commitments, too.

All greenhouse gas emissions matter, but large countries’ emissions matter most.

The potential impact on global climate policy momentum leads to questions about the federal government’s assertion that US greenhouse gas emissions have limited influence on the global climate.

In the documentation supporting the endangerment finding rescission, EPA states that “reducing greenhouse gas emissions from all vehicles and engines in the United States to zero would not have a scientifically measurable impact on greenhouse gas emission concentrations or global warming potential.” This statement is dubious on its face: according to EPA, 29 percent of total US greenhouse gas emissions are from transportation, of which more than three quarters are from road vehicles. These road vehicles alone emit over a billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, exceeding the total annual greenhouse gases of all but a handful of countries, each with their own obligations under the Paris Agreement.

EPA’s statement ignores the political dynamics inherent to global climate policy, which requires all emitters to cooperate for the greater good. Individual countries can contribute only a minor share toward the stabilization of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The United States emits 11 percent of greenhouse gases today, second only to China with 30 percent of global emissions, and followed by India and the European Union with 8 percent and 6 percent of global emissions each. The other 45 percent of global emissions are shared among the more than 160 other countries of the world.

Thus, a free-rider issue extends through global climate policy. Countries bear high costs to decarbonize, but the benefits are shared by all countries. At the same time, individual climate action without buy-in from the rest of the world not only limits benefits to the mitigating country, but potentially puts the proactive country at a competitive disadvantage if the costs of mitigation increase the prices of export goods.

Breaking the free-rider problem has driven decades of multilateral climate policy cooperation—culminating in the Paris Agreement.

The United States influences climate policy momentum.

Countries with large emissions profiles are especially capable of influencing the momentum of global climate policy. These nations can create multiplier effects in both positive and negative directions. Ahead of the twenty-first Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris that led to the eponymous agreement, the United States and China—as the world’s largest economies and emitters—engaged in some careful bilateral diplomacy that resulted in a “G2 agreement.” This agreement contained new climate pledges and signaled to the world the importance of agreeing on a new international climate policy framework, while also committing to concrete policy actions such as the United States’ Clean Power Plan and China’s target to reduce its carbon intensity per unit of GDP.

Even in the early stages of international climate policy, the convening power of the United States was used to great effect in establishing an international framework in the first place. It was the H. W. Bush administration that agreed to the UNFCCC in 1992, and submitted it to Congress, which ratified it the same year. A Senate resolution endorses the UNFCCC to this day.

While the United States leaving the Paris Agreement once more is a blow for global climate policy, the “Paris structure” can in principle withstand countries abandoning or downscaling their climate policy pledges; it was never likely that 200 countries would always be on the same page. But in the pledge-and-review process of the Paris Agreement, the NDCs of large economies are particularly important: an NDC perceived as ambitious might spur other countries to strengthen their own pledges, while pledges perceived as being comparatively modest would see such peer pressure diminished. On top of that, the actual commitments of NDCs, and especially their implementation, could support climate action abroad in terms of financing, clean technology costs, and other spillovers.

Even though the rest of the world continued to implement climate policy after the first US withdrawal under the first Trump administration, more severe spillovers may ensue this time. The United States elected President Donald J. Trump again, when his stance toward climate change was more well known and strident. This repeated US reticence on climate policy leads to a persistent credible commitment problem.

Other countries will be asking if the regulatory repeals can withstand court challenges and how easily a more pro-climate administration could reinstate both the endangerment finding and related regulations. Such uncertainty could affect the ambition of other governments.

In the past, US actions could be interpreted as disagreement with the legal form of an international agreement (concerns sometimes shared by other countries). But now, the United States appears to have shifted toward hostility, exacerbating the free-rider problem inherent to climate policy. The United States’ actions could move countries to believe that their domestic actions are in vain if the rest of the world does not follow. A self-fulfilling prophecy might ensue.

Other countries’ Paris pledges may be weaker without US commitment.

It is against this background that the repeal of the endangerment finding, and especially the repeal of associated federal climate policy regulations, could reverberate through the international community. The Paris architecture can deal with any country—even the world’s largest historical emitter—stepping in and out of the agreement. But actions that make it harder for future US governments to enact climate policies would not go unnoticed and may over time lead to a negative multiplier effect.

Some anecdotal signs already indicate that other countries are reacting to the United States’ climate negativity with negativity of their own. Indonesia’s special envoy for climate stated in January that his own country might consider leaving the Paris Agreement, saying that it is unfair for Indonesia to commit to climate action if a large country like the United States abandons the agreement. Argentinian President Javier Milei likewise expressed his desire for Argentina to leave the Paris Agreement. In New Zealand, one of the government coalition partners raised the possibility of leaving the Paris Agreement after the next national election in 2026. In the European Union, a former climate commissioner warns against “green backsliding.”

Another impact of the US withdrawal from the international climate stage is felt in its foreign assistance. South Africa was counting on financial support from the United States to gradually decommission coal-fired power plants, which will no longer happen due to the United States also withdrawing from the Just Energy Transition Partnership that supports the energy transition in emerging economies. Stakeholders in India expressed concerns about ripple effects for green hydrogen development and capital to finance clean technology investments.

But evidence for any multiplier effect, positive and negative, will be found in future NDCs. As it happens, the 2025 COP30, hosted by Brazil, will be the first annual climate conference after the new round of NDC submissions are due. The deadline to submit the new NDCs was initially set for February 2025 but later extended to September 2025. So far, only about 20 parties have submitted NDCs. Missed deadlines in multilateral forums are not necessarily unusual, given that each party will be constrained by its own domestic political circumstances. But it remains to be seen how many NDCs will be submitted and how ambitious the pledges contained therein will be.

In contrast, for the COP26 in Glasgow, which took stock of the first set of NDCs, well over 100 parties submitted NDCs, with most having done so well in advance of the conference. This included the United States, as President Joe Biden reversed the decision to leave the Paris Agreement only a few months after the US withdrawal had taken effect but before COP26, which was delayed by a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even after the 2024 US election, the Biden administration still submitted a revised NDC for 2035, committing to 61–66 percent emissions reductions by 2035, compared to 2005. This revised NDC could be seen as a signal of what a future administration committed to climate policy might want to achieve.

But if actions are now undertaken to constrain the future regulatory capabilities of the federal government, other countries might adjust their expectations of what the United States can achieve over the next decade. Expectations about the relative supply and costs of fossil fuels versus clean technologies could lead to other countries moderating their NDCs. For poorer economies, expectations of reduced international climate finance could reduce the willingness to adopt more ambitious pledges.

In the European Union, lack of momentum is also visible. The world’s second-largest economy traditionally sees itself as a front-runner in climate action and has indeed legislated extensively to achieve its 2030 climate target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 55 percent compared to 1990. For 2040, its proposed target is a 90 percent emissions reduction compared to 1990. The European Council—the body representing the EU countries’ heads of government—so far has not formally agreed to this target, which means the European Union has delayed its NDC for 2035, which depends on its 2040 target. EU decisionmakers cite ongoing challenges to industrial competitiveness and high energy prices. But the knowledge that the world’s largest economy is unwilling to commit to further climate action does not help the case of those promoting climate action in Europe.

Perhaps the most critical NDC will be the one that the world’s largest emitter, China, submits. In its current NDC, its main target is to ensure that its greenhouse gas emissions peak before 2030. China moving toward an absolute emissions reduction target would send a signal to other emerging economies to consider similar carbon constraints. The absence of a new US NDC, however, will remove any peer pressure from its greatest geopolitical and economic rival to enhance its current ambition.

The Paris Agreement is working, even if change is slow.

So far, the United States is the only country to have gone as far as to leave the Paris Agreement. But even without other parties jumping ship, the agreement is not without its critics. Critics point to global emissions, which have yet to peak even if their growth has slowed. China’s progress in implementing its current NDC is critical here.

The fact that global emissions haven’t peaked yet is not necessarily evidence of the inadequacy of the Paris architecture. Paris Agreement implementation is a bottom-up process, much like global emissions are the result of thousands upon thousands of individual actions and policies.

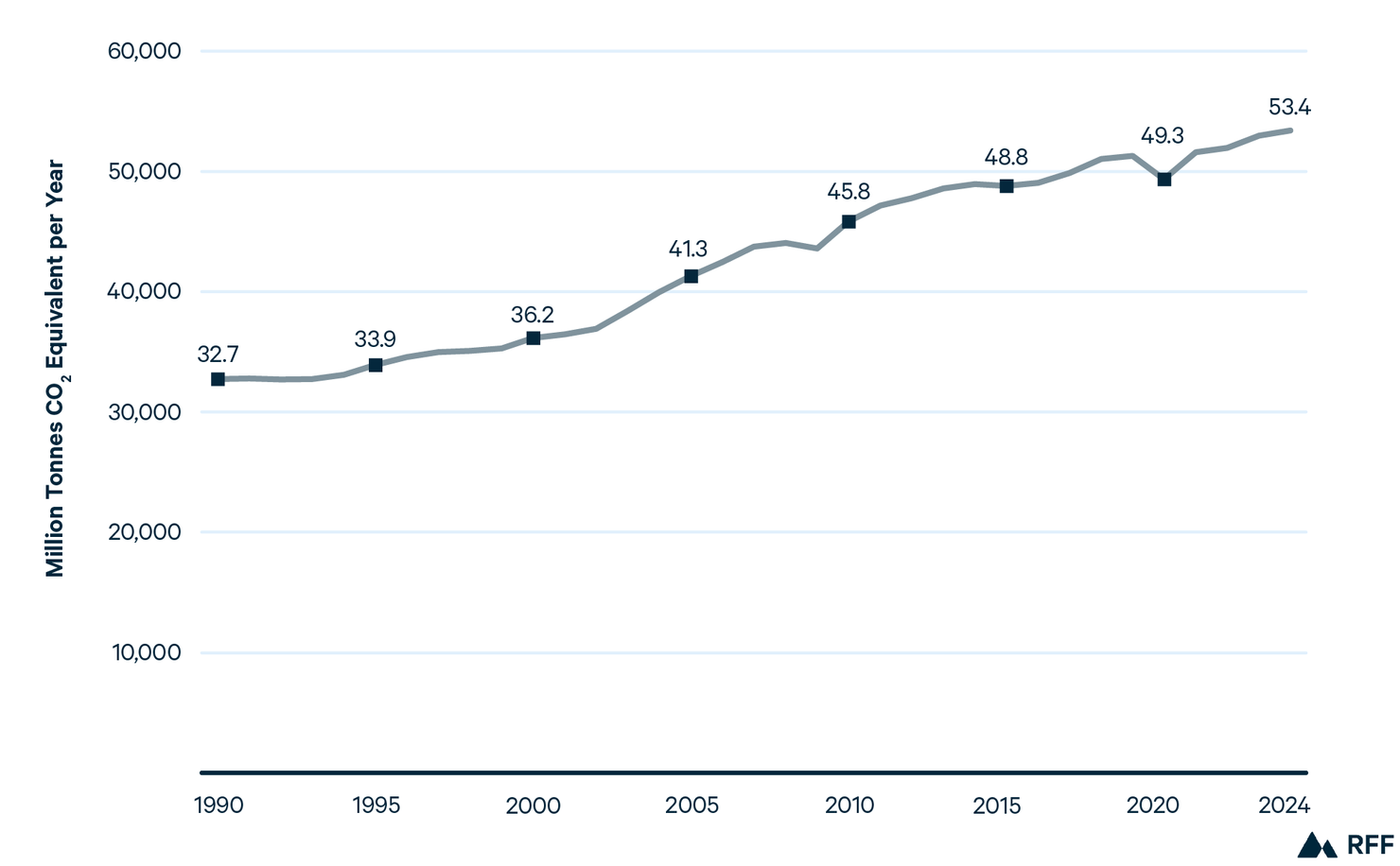

In such a bottom-up structure, and against a historical background of emissions increasing year over year, it is virtually inevitable that we first observe a period of slower growth and flatlining emissions. That is what has been happening since 2015, with annual global emissions having grown by just under 5 gigatons over the past decade, compared to an increase of about 10 gigatons during the first decade of this century.

Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 1990–2024

Source: The European Commission’s Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research, 2024. The 2024 value is our own estimate based on the reported global carbon dioxide emissions growth rate of 0.8 percent.

The only binding parts of the Paris Agreement (insofar as anything can be binding under international law) are the processes surrounding NDC submissions. It is not obvious that another international climate policy architecture would fare better given the challenges of multilateral cooperation.

The NDCs will always reflect global geopolitics and macroeconomic conditions. What is certain, however, is that large economies can influence the NDCs of other parties for better or worse. It also means that with a true loss of momentum, estimates about global emissions trajectories and temperatures might need to be revised again, but now in an upward direction (after estimates of global warming by 2100 were reduced several times based on NDC pledges). The damages from climate change would then increase in the United States and globally.

No country truly stands or acts alone in global climate policy. It is against this background that the United States’ choice to reduce its own capabilities to take regulatory action and adopt stronger pledges under the Paris Agreement in the future might be very costly for itself and the rest of the world in the long run.

For more timely insights about developments in environmental and energy policy, browse the If/Then series.