Through its recent cancellation of two dozen major energy projects, the US Department of Energy may compromise US industrial competitiveness in a global economy that’s decarbonizing.

On May 30, 2025, the US Department of Energy (DOE) announced the termination of 24 funding awards for clean energy demonstration projects that were administered through the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, citing $3.7 billion in projected taxpayer savings. However, the announcement contained limited details on the substance of these terminated grants or what would be lost through their cancellation. In addition to the immediate losses for project sponsors, the termination of demonstration projects could stunt technological advances in clean energy, potentially hurting US opportunities for international competitiveness and leading the field in the global landscape. Without compelling evidence to the contrary, we argue that the cancellation of these projects may cost the United States (and the world) more than it saves for taxpayers. Maintaining investments in industrial decarbonization could deliver major benefits to domestic industry while supporting US competitiveness, not to mention also facilitating carbon dioxide reductions that help slow climate change at a cost lower than the social cost of carbon for some projects.

The List of Terminations

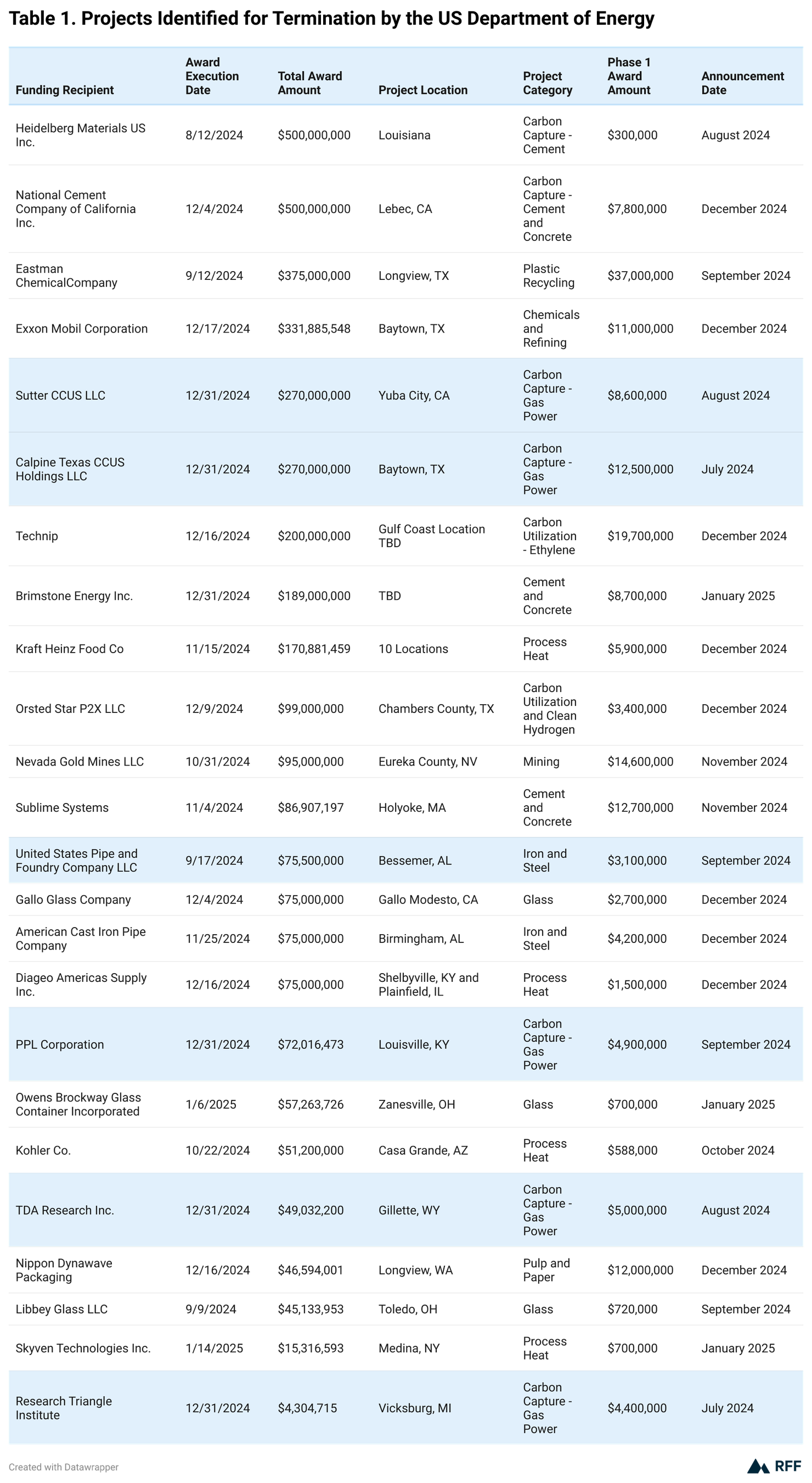

A list of terminated projects has now emerged, which we have amended to include two more columns that cover project categories and disbursement amounts and dates (Table 1).

Sources: Award Wednesdays | August 7, 2024 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesdays | August 14, 2024 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesdays | August 28, 2024 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesdays | September 12, 2024 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesdays | September 18, 2024 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesdays | November 13, 2024 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesdays | December 4, 2024 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesdays | December 11, 2024 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesdays | December 18, 2024 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesday | January 8, 2025 | Department of Energy, Award Wednesdays | January 15, 2025 | Department of Energy, Baytown Carbon Capture and Storage fact sheet, Industrial Demonstrations Program Selected and Awarded Projects: Cement and Concrete | Department of Energy, Industrial Demonstrations Program Selections for Award Negotiations: Chemicals and Refining | Department of Energy, Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations Award Wednesday Updates

Our amended project list conflicts somewhat with DOE statements about the timing and cost savings associated with DOE’s terminations. For example, DOE stated that nearly 70 percent (16 of the 24 projects) were signed between Election Day 2024 and January 20, 2025; however, six of these projects (highlighted in blue) were signed much earlier. For example, the Calpine Texas CCUS Holdings LLC project was listed in the termination notice from DOE with its termination notice with an “award execution date” of December 31, 2024, but the Biden administration’s DOE announced that the project had been awarded the first payment of $12.5 million on July 3, 2024.

Furthermore, most projects already had been awarded the first tranche of funding—totaling over $171.9 million in awarded funds—by the time of termination. Minus first-phase awards to date, the total value of grants that were terminated is $3.55 billion. A possibility is that DOE plans to reclaim obligated or disbursed funding, but this reappropriation would present legal challenges, and the issue is not addressed in DOE’s statement.

The Review Process

In the cancellation notice, DOE provided a set of goals or criteria against which projects were assessed, including whether projects “failed to advance the energy needs of the American people, were not economically viable, and would not generate a positive return on investment of taxpayer dollars” and did not align with “national and economic security interests.”

Addressing Energy Needs

A review of the canceled projects suggests that a range of energy needs actually were being addressed by the projects as they stood. Some of the canceled projects were funded to advance relatively undeveloped energy sources, such as hydrogen, for use in industrial processes (e.g., Exxon Mobil’s project). Other projects aimed to use new energy sources in novel ways, a strategy that can increase the demand for such sources and therefore help create viable markets. Many of the projects related to decarbonizing industry and further developing technologies for carbon capture and storage (e.g., Sutter Decarbonization Project). Particularly when applied to natural gas, technology demonstrations of carbon capture and storage advance the viability of fossil fuel sources of energy while addressing climate change.

Economic Viability

Insufficient information is available to the public to determine whether some of the canceled projects may have generated financial losses in the short and long term, or whether investments ultimately would be paid off. For technologies to get as far as winning a grant competition, however, applicants must have had success in technology development (e.g., at the pilot stage), been ready to scale up to the demonstration level, and made the case that the technology eventually would be economically viable.

Regardless, an evaluation of economic viability and positive returns on investment, with respect to government investments such as these terminated grants, should involve assessment of all benefits and costs to society. Positive externalities, such as reductions in carbon dioxide emissions, should be included. By our analysis, some of these canceled projects cost less to reduce carbon emissions than the social cost to society of the emissions, as measured by the social cost of carbon—evidence for a positive societal return on investment.

For example, the Calpine Texas carbon capture project was projected to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by two million metric tons annually—roughly equivalent to the emissions of 450,000 gasoline-powered vehicles. With a federal cost share of $270 million and an estimated total project cost of $540 million (based on the assumption of a 50 percent cost share), as relayed in a related press release, the project would yield lifetime capital expenditures of approximately $18 per ton of carbon dioxide avoided over 15 years, albeit not counting the considerable operating costs. We estimate that operation and maintenance costs could increase the figure by an additional $30 per ton (with further additional costs of moving and storing the carbon dioxide permanently). Even with the additional costs, however, the total costs would be well below the social cost of carbon used by the US Environmental Protection Agency during the Biden administration ($190 per ton and up).

(The operation and maintenance cost per ton of carbon dioxide abated was estimated by dividing the total annual operation and maintenance costs—estimated using the fixed [$28.89 per kilowatt-year] and variable [$6.11 per megawatt-hour] rates in the Annual Energy Outlook 2022 from the Energy Information Administration—by a power plant’s annual carbon dioxide–capture target of two million metric tons. The plant capacity was assumed to be 810 megawatts [based on the project’s original fact sheet], assuming an 85 percent capacity factor and a 90 percent carbon dioxide capture rate, resulting in an operation and maintenance cost of approximately $30 per ton of carbon dioxide captured.)

Extending this simple analysis to other projects that estimate carbon dioxide reductions, we find estimates as low as $6.33 (Nevada Gold Mines LLC) and $16.39 (Exxon Mobil Corporation). However, this low cost is not the case for all projects. The same type of analysis for the Brimstone Energy project that aims to decarbonize the cement sector, for example, yields a capital expenditures estimate of $328 per ton—well above the social cost of carbon.

Even when current costs are high per ton of reduced carbon dioxide, innovation demonstration projects may bring costs down in the future. Decarbonization demonstrations are an important first step toward much greater and more cost-effective emissions reductions. For example, the cement industry is considered a hard-to-abate sector, accounting for 7.5 percent of global emissions, and with demand expected to increase over time. Therefore, a successful demonstration of cement decarbonization could lead to much greater reductions in national and global carbon dioxide reductions, through economies of scale, continued innovation, and lower costs per ton.

National and Economic Security and Innovation

National security and economic security improve when US industries become or remain competitive on the world stage. As other countries decarbonize their industries, these funding terminations by DOE could make the United States less competitive. As global markets begin to account for the carbon intensity of traded goods via carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs), and supply chains are incentivized to shift toward cleaner production, clean technology demonstration projects take on heightened importance for national security. In fact, a key rationale for funding demonstration projects lies in their potential to generate knowledge spillovers and de-risk technologies, which will benefit future deployments. The goal is not simply to reduce emissions from one facility, but to demonstrate the technical and economic feasibility of novel processes that can be replicated and refined over time.

RFF has discussed these issues in the past, with previous work highlighting the opportunities and challenges of demonstration projects funded by the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. In that published report, the authors emphasize that learning potential, market creation, and total potential abatement are vital metrics to consider, with benefits of future deployment often well exceeding direct benefits.

The canceled projects in the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations were targeting many hard-to-abate sectors. As a result, project cancellation risks the loss of novel innovation that otherwise could decarbonize entire industrial sectors.

Many terminated projects targeted sectors in which little commercial precedent exists, including clean hydrogen production, low-carbon cement, and low-emissions steelmaking. For example, American Cast Iron Pipe Company intended to use funding from the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations to upgrade its processes and eliminate the combustion of petroleum coke, updates which could be replicated throughout the iron pipe industry and support new industries such as chip and battery plants. Therefore, a cost-benefit analysis also should consider the decarbonization potential of the iron and pipe industry and the learning spillovers for new industries. As another example, Libbey Glass LLC intended to demonstrate the viability of hybrid electric furnaces, which could be scaled for the entire glass industry. Similar ambitions can be found across many projects, increasing project benefits.

Consequently, these grants offered potential benefits for long-term national security and international competitiveness. Policies such as the EU CBAM, the UK CBAM, and similar initiatives emerging in other jurisdictions aim to level the playing field by imposing carbon tariffs on imports in certain carbon-intensive sectors. Many of the projects now canceled by DOE targeted the decarbonization of core CBAM-regulated industries like cement, aluminum, and iron and steel (e.g., Brimstone Energy for cement and United States Pipe and Foundry Company for iron and steel).

Even if the United States continues to avoid direct domestic carbon pricing, US exporters will increasingly face carbon costs in international markets. Meanwhile, competitors remain incentivized to develop clean industrial technologies and already are investing in similar projects (e.g., the Clean Industrial Deal in the European Union), providing the potential for other countries to leapfrog the United States and gain supply-chain advantages.

Additionally, at the heart of domestic congressional proposals, such as the Clean Competition Act and Foreign Pollution Fee Act in the United States, is the assumption that American industry is already relatively carbon efficient, providing a “carbon advantage.” These two proposals benchmark against US intensities to determine fees from other countries, making it beneficial for the United States to maintain a lower carbon intensity for these heavy industries—which the United States risks losing as other countries invest in deep decarbonization.

In short, these clean energy demonstration projects are not just about emissions—they would have helped preserve US industrial leadership and competitiveness in a decarbonizing global economy. If US industrial sectors do not decarbonize, the United States risks losing its carbon advantage and paying a (carbon) price for its pollution, while forfeiting an opportunity to be a leader in low-carbon industrial trade.

Conclusion

We’ve noted a lack of transparency around DOE’s decisionmaking, including our observation of no detailed cost-benefit analyses, no clear evaluation criteria, nor even consistent documentation of award dates and funding levels. As a result, the American public has a limited ability to evaluate whether these cuts will save taxpayer funds and benefit society on net. If DOE wishes to build public trust in its decisionmaking for canceling or keeping projects, making their analyses publicly available will be an important step.

Indeed, our initial (and rudimentary) analysis suggests that many of the projects that DOE canceled could have generated long-run public returns—and potential short-run financial returns—in terms of emissions avoided, technologies de-risked, and strategic positions secured. At a moment when global clean energy leadership is up for grabs, the decision to pull support from US clean energy projects midstream could detract from American prospects for future innovations and carbon dioxide reductions. If the administration feels otherwise, let’s see the evidence.

For more timely insights about developments in environmental and energy policy, browse the If/Then series.