If the United States exports vastly more fossil fuels to the European Union, Then the fossil fuel trade will run up against long-term EU climate goals.

The United States and the European Union recently agreed to a trade arrangement around energy. Specifically, the European Union will buy $750 billion worth of liquefied natural gas, oil, and nuclear fuel from the United States before the end of 2028. However, this commitment has raised eyebrows. $250 billion a year for three years triples the annual value of US energy exports to the European Union from current volumes, transforming the transatlantic energy relationship. In the long term, fossil fuel consumption by the European Union without the use of carbon capture technologies (also referred to as unabated consumption) would challenge established EU climate goals.

In this blog post, we estimate the carbon intensity associated with the EU consumption of fossil fuels under this deal to be 1.5 gigatonnes of greenhouse gases per year, with the majority coming from crude oil. Depending on the energy sources that are displaced in the European Union, the change in supply-chain emissions, and the effects on global energy prices, the new agreement may not translate into an increase in EU emissions. But how long will any US-EU energy trade last, given the emissions associated with fossil fuel consumption?

The US-EU Energy Relationship Today

The European Union notes that it buys around $90 billion–$100 billion in energy products per year from the United States, though independent analyses peg that value closer to $70 billion. A $250-billion commitment therefore represents a significant increase that inevitably will displace other EU energy supplies. The European Union produces about 10 percent of the natural gas it consumes while importing significant volumes from Norway, Algeria, and Qatar. Russian gas imports account for 13 percent of EU consumption, but the European Commission recently elected to ban Russian imports by 2027.

However, the EU demand for energy—especially for unabated fossil fuels—is on the decline. EU energy-efficiency targets aim to reduce energy consumption by 11.7 percent in 2030 compared to 2020, while renewable energy mandates also will chip away at fossil fuel demand. Even if the deal is followed to the letter, the European Union will not be in a position to continue high volumes of energy imports from the United States in the long term, as its climate policies will not allow for large volumes of unabated fossil fuels for much longer.

What Does the Deal Mean for EU Emissions?

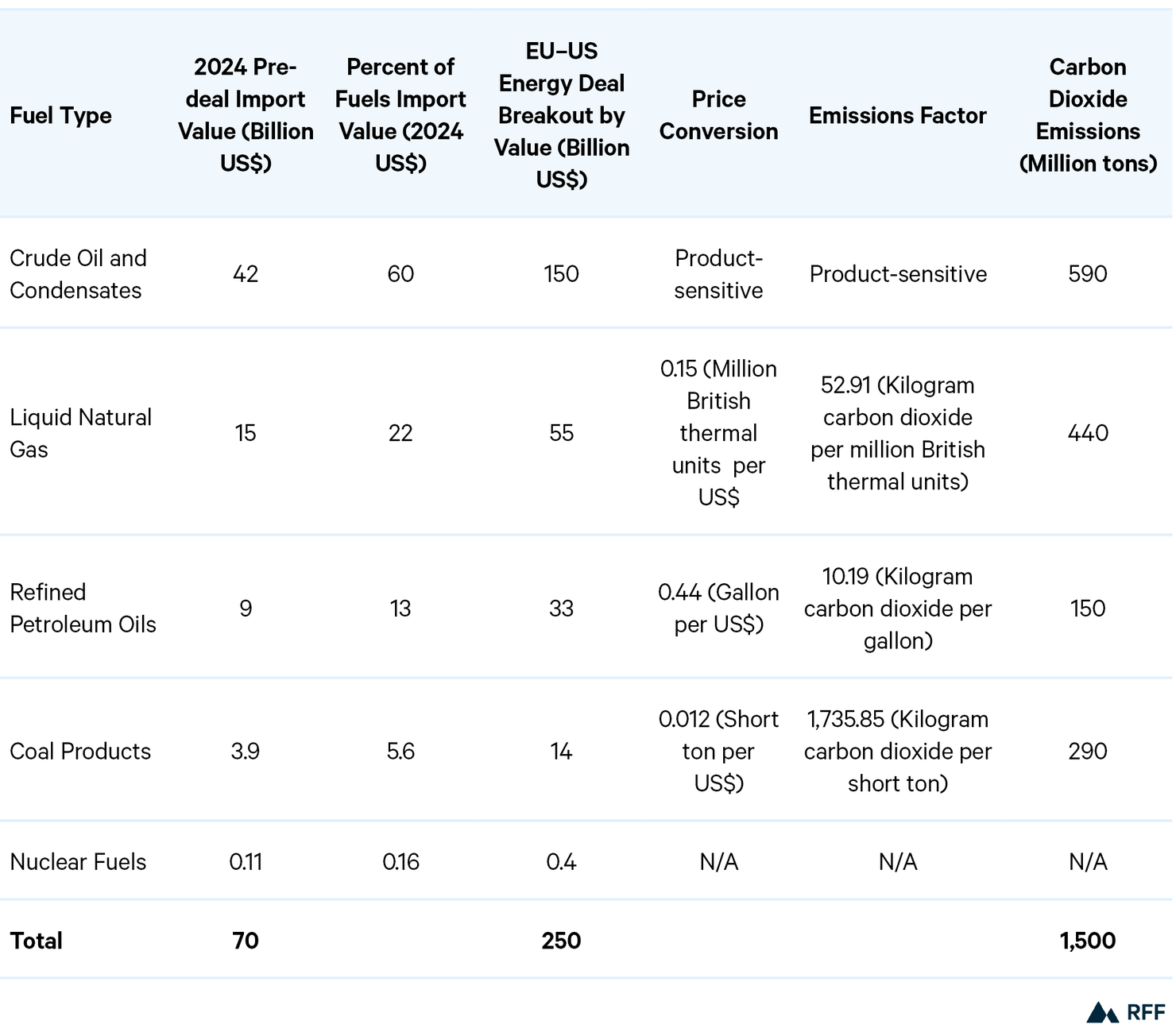

Below, we focus on the direct emissions associated with the consumption of US energy imports, as the European Union’s own increasingly stringent climate and energy policies limit how much carbon dioxide can be emitted within EU borders. We translate the dollar value of energy imports defined in the agreement into emissions estimates from the consumption of these fuels, totaling 1,500 megatonnes (i.e., 1.5 gigatonnes) (Table 1). We based this calculation on several assumptions.

Table 1. Trade Volumes and Emissions Factors for Select Fuels

We account separately for energy fuels headed to refineries and adjust for trade patterns of refined products, which have different emissions factors set by the US Energy Information Administration. Nuclear fuels are treated as non-emissive in the estimate. Percentage totals do not sum to 100 due to rounding. “Emissions factor” means the quantity of carbon dioxide produced by the combustion of a unit of fuel.

We limit our scope to fuels covered by fact sheets released by the White House and European Commission, which include crude oil, diesel, liquefied natural gas, coal, and nuclear fuels. We exclude fuel services because available data covers traded goods, with uncertainty over what services would be included as qualifying investments. We base each fuel’s future share of trade on the fuel’s respective 2024 import value where available.

After we obtained the breakdown of total fuels imported into the European Union from the United States in 2024, we converted these import ratios to emissions estimates assuming the following three things: the European Union buys $250 billion of fuel per year from the United States, each commodity is sold for the average 2024 price, and the emissions factors are those from the US Energy Information Administration. The Energy Information Administration reports that burning natural gas, for example, emits 52.91 kilograms of carbon dioxide per million British thermal units. Using this value, we find that emissions linked to the consumption of US liquefied natural gas imports would grow from roughly 130 metric tons today to 440 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent under the deal.

Analyzing the carbon implications of the deal requires certain caveats. First, US energy supplies to the European Union include fuel for carbon-neutral nuclear energy. Second, since greenhouse gas emissions matter for climate goals, not fossil fuel consumption, in principle the European Union could continue to consume any volume of fossil fuels indefinitely, provided the emissions are abated through carbon capture and storage. We adjust for the proportion of refined petroleum products exported out of the European Union, as we are interested only in emissions from EU fuel consumption.

Declining EU consumption of liquid fuels (like gasoline and diesel) and limited petroleum refining capacity could affect EU imports of fossil fuels. Refineries are configured to process certain grades of crude oil for certain refined products. Besides crude oil, the European Union also imports refined products such as diesel, while exporting other refined products such as gasoline. The fact that the EU imports certain refined fuels while exporting others is reflected in trade patterns. Over time, EU demand for specific refined products such as diesel may decline because of ongoing transitions in the European Union’s vehicle fleet.

Since the US-EU deal targets a specific US dollar amount, vastly higher energy prices (or exchange rates leading to the same effects) would decrease the carbon footprint of a given dollar amount of energy purchased. But higher energy prices make it more attractive for consumers in industry and households to seek higher energy efficiency or alternative energy sources, irrespective of climate concerns.

How Do These Emissions Jibe with the European Union’s Goals?

The 1.5 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions that this deal would create represents roughly a quarter of EU greenhouse gas emissions in 1990—its baseline year—and about half of current EU emissions, which sit at just over 3 gigatonnes.

According to the European Union’s own climate policies, its annual emissions should be lower by the mid-2030s. If sustained, the estimated carbon footprint of 1.5 gigatonnes would consume roughly 60 percent of the entire 2030 EU emissions target and 250 percent of the 2040 proposed target. The European Union does not have an explicit carbon budget, i.e., an unambiguously agreed-upon quantity of greenhouse gases that can be emitted over a certain period. But the European Union does have several legally binding climate targets and policies that create implicit carbon budgets. The legislation described below, in particular, is incompatible with the emissions footprint of 1.5 gigatonnes implied by the energy deal.

The European Climate Law codifies the European Union’s net-zero greenhouse gas emissions target for 2050 (i.e., climate neutrality). For 2030, a net 55 percent emissions-reduction target compared to 1990 is in place, while for 2040, the European Commission proposes a reduction of 90 percent. This target still needs to be formally adopted by the European Union (EU environment ministers agreed to the target on November 6), including details on carbon removal and international credits. In 1990, EU greenhouse gas emissions totaled 5.65 billion metric tons, which leaves 2.54 billion metric tons for 2030 and 565 million metric tons for 2040.

Policies such as the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) provide additional constraints on EU fossil fuel demand. Natural gas demand, for example, will be affected both by the ETS 1 cap (covering power and industry), which under current legislation will fall to zero tons of covered greenhouse gas emissions in 2039, and the ETS 2 cap (covering upstream energy supplies for heating in buildings), which will start at 1.036 gigatonnes in 2027 and decline by a fixed quantity every year thereafter. Slower-than-expected abatement in industrial sectors that emit non-energy process emissions leaves less “carbon budget” for combusting gas under ETS 1. A faster uptake of electric vehicles leads to less demand for refined oil products, but also leaves more of the carbon budget in ETS 2 for gas consumption to heat homes.

Potential Significance of This Agreement

All in all, while the European Union could certainly replace some of its fossil fuel imports from countries like Algeria and Russia with more US imports over the next few years, the European Union’s own climate targets make it highly unlikely that the European Union will be buying more energy from the United States a decade from now unless the imports contribute to a low-carbon energy system.

The concern of stranded assets also is a consideration. Replacing natural gas delivered to the European Union from neighboring countries via pipeline with liquefied natural gas brought over via ship requires new infrastructure for liquefaction and transport. Financing terminals with a limited expected lifetime is challenging.

Energy trade and consumption—even when it involves diplomacy and trade negotiations —are primarily the result of decisions by individuals and companies in the marketplace. All the more reason to not bank too much on this deal being transformational for the transatlantic energy relationship: the arrangement goes against the grain of the European Union’s long-standing policy to transition to a lower-carbon energy system.

For more timely insights about developments in environmental and energy policy, browse the If/Then series.