If funding through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Community Change Grants Program is withheld, Then communities across the country will miss out on a historic investment in basic infrastructure and workforce development.

In December 2024, the northernmost US city of Utqiagvik’s electricity cooperative and a team of University of Virginia researchers were selected for a Community Change Grant (CCG) from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to conduct a stormwater drainage study, along with other basic infrastructure activities. The partnership wanted to tackle a variety of local problems, one being the persistent flooding of the community’s only cemetery. The collaboration also planned to use EPA funds to upgrade Utqiagvik’s heavy-duty maintenance vehicles, machines necessary for a community to thrive in Arctic conditions. For 90 percent of the year, Utqiagvik’s temperature dips below freezing.

Community Change Grants were funded by the Environmental and Climate Justice Program, which was established by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. This program, in turn, has since been declared “terminated” and unobligated grants rescinded by the recent reconciliation bill that passed into law on the Fourth of July. However, court documents show that much of this funding was indeed obligated and available to recipients through the federal Automated Standard Application for Payments portal prior to the funding cuts at EPA that were implemented this year by the Department of Government Efficiency. Up until the current uncertainty about the status of these Community Change Grants, the $1.6-billion-dollar program was poised to bring improvements to public services in communities across the country.

Community Change Grants

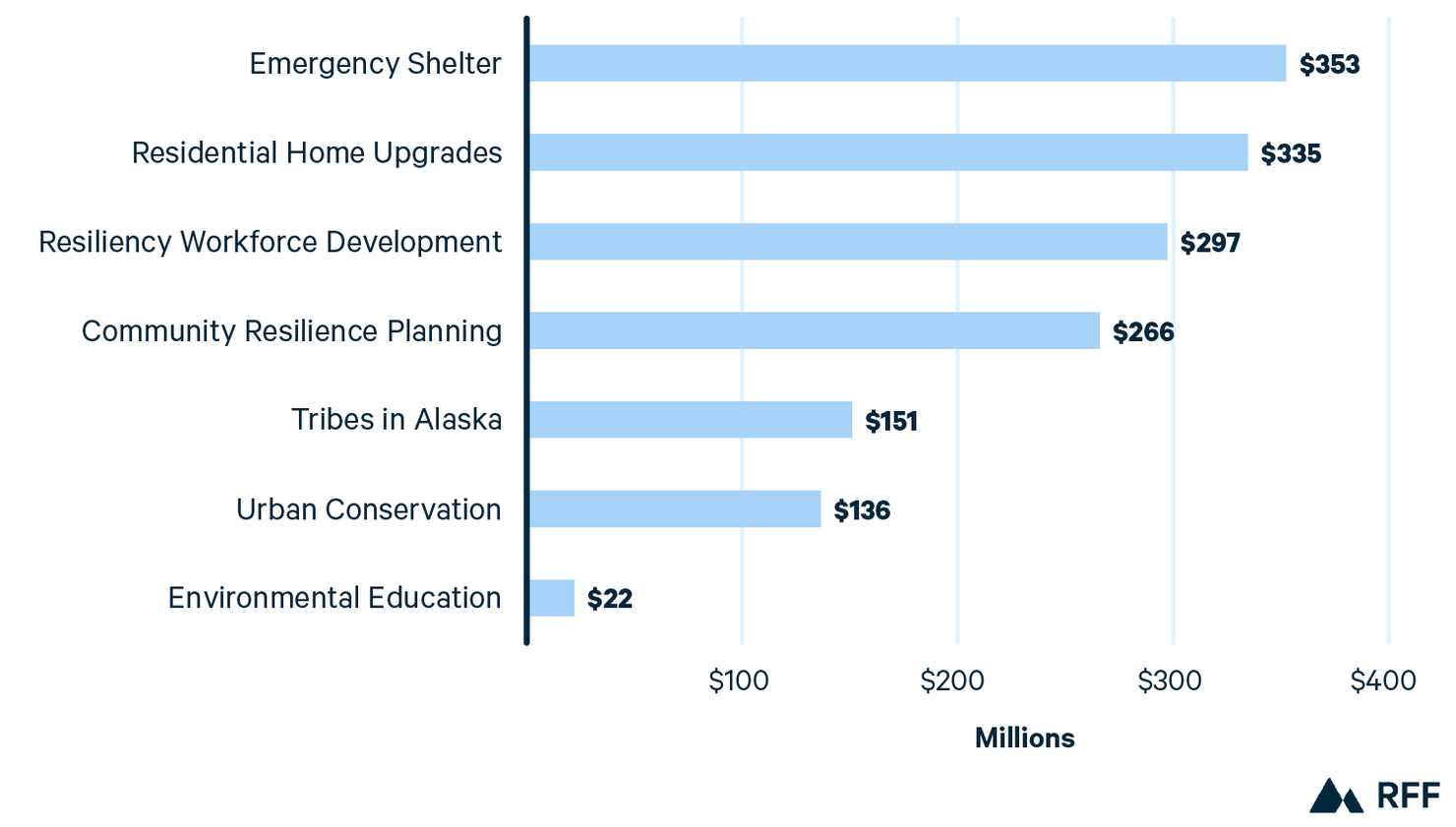

The CCG Program predominantly funded investments into the built environment and human capital of US communities that have below-average income and above-average minority population. A topical analysis of the project descriptions of all CCG awards indicates that grant awardees strove to enhance protection from natural disasters, develop a local workforce capable of dealing with engineering problems, and reduce residential energy costs (Figure 1). A large share of the funds went to projects that support critical infrastructure for the Alaska Native population.

Figure 1. Breakdown of the $1.6 Billion in Funding Through Community Change Grants

Data source: Archived webpage of the Community Change Grant Program selections

The figure above breaks down the $1.6-billion CCG Program by topical area of project focus. The program invested $353 million into projects that establish emergency shelters for communities in the event of natural disasters; for example, the Benton Harbor community center restoration or the Spokane resilience hub project. Building out this infrastructure requires a trained workforce, the development of which accounts for another large area of spending in the CCG program that totaled $297 million. Many projects, summing to $335 million, aimed to upgrade residential HVAC systems and weatherize households, which reduces energy costs. $151 million went to Tribes in Alaska, with awardees sharing similar activity goals with other projects. The average grant awarded by the program was just shy of $15 million.

Lost Partnerships and Benefits

CCG applicants were, as per federal regulations, a partnership that involved a community-based nonprofit organization and one other entity: either another community-based nonprofit organization, a Tribe, a local government, or a university. This approach to economic development is designed to get federal funds into the hands of local institutions that work directly in their communities, rather than to bureaucracies that may be overwhelmed or ill-informed. Researchers have argued that community-based partnerships are effective tools to bring critical infrastructure to places that lack government capacity. Resources for the Future has published research on oil and gas communities that documents the difficulties rural communities face when attempting to access federal funding opportunities.

The expected outcomes across these partnerships ranged widely, but most had estimated quantifiable benefits.

For example, much of the Community Change Grant funding went toward planning for natural disasters and establishing community emergency shelters for disaster contingencies. According to the US Chamber of Commerce and the Allstate insurance company, such basic measures can save $13 in costs for every dollar invested.

Improving the environmental quality of American communities by investing in urban conservation, another expected output, creates public spaces that boost local economic activity. Public investment in local colleges and universities for workforce development confers proven economic benefits to regional economies. In fact, economic-development practitioners refer to local educational institutions as “anchor institutions,” because these academic spaces often serve as resilient employers and sources of demand for local goods and services. The return on investment for public spending on residential home upgrades is less clear, but recent research suggests that energy-efficiency improvements and HVAC upgrades have been effective in reducing household energy bills.

Opportunity Costs

For local governments and community-based organizations in the most remote and under-resourced areas of the country, the Community Change Grants offered a different model of working with the federal government. It can be wasteful to pour federal resources into aligning and coordinating the patchwork of state, county, municipal, Tribal, and local governments to deliver on civil infrastructure. That endeavor is a risk, especially when any one of those entities is limited in its capacity to take on new projects. Why not, then, fund partnerships between community groups, universities, and local governments that presently are delivering services to their communities?

Finally, program terminations and grant recissions are inefficient in many ways, not the least of which is the time and money that local organizations have invested in building successful partnerships and applications. Those hours spent on CCG applications could have been directed toward productive activities with greater durability in the event of a change in federal policy. New research is warranted on how communities can be insulated from these policy uncertainties.

For more timely insights about developments in environmental and energy policy, browse the If/Then series.