US energy has been moving away from coal for decades. The Trump administration’s policies that are friendly to coal mining and coal-fired power raise questions about the future impact of coal on the energy economy, air quality, climate, and public health.

Whither Goest Thou, Coal?

Coal is a declining, yet still significant share of US electricity generation and continues to emit pollutants that affect climate and public health. In 2024, coal accounted for 15 percent of electricity generation but was responsible for almost half of carbon dioxide emissions from electricity generation. Coal combustion emits numerous other air pollutants, including nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, fine particulate matter, and mercury. These pollutants contribute to ambient concentrations of ozone and PM2.5 (particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less), which cause premature death, hospitalizations, asthma attacks, and other health effects. These air pollutants from burning coal also contribute to sulfur and nitrogen deposition, which can adversely affect ecosystems.

At the same time, coal mines and coal-fired power plants are important contributors to local economies in several US regions, including parts of Appalachia, the Midwest, and the Intermountain West. Mines and power plants typically offer well-paying jobs and contribute significantly to the local tax base, helping to fund schools, roads, and other essential public services.

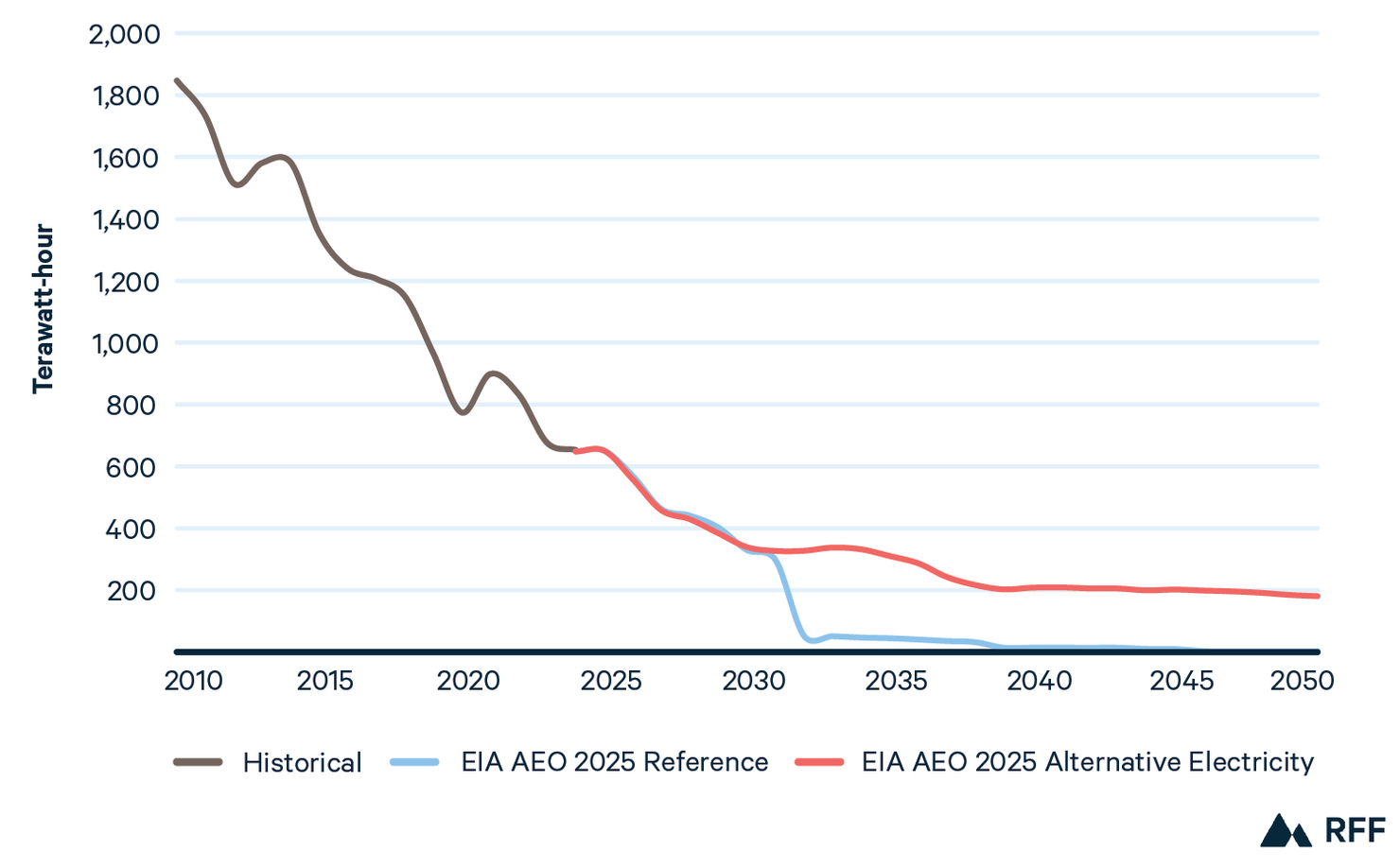

The US Energy Information Administration’s 2025 Annual Energy Outlook report (produced largely before the Trump administration’s policies took effect) projected in its reference case that electricity generation from coal would decline by almost 50 percent from 2024 levels by 2030, and 93 percent by 2035. These projections include anticipated effects of the standards that limit greenhouse gas emissions from existing steam-generating units powered by coal, oil, and natural gas, and new combustion turbines powered by natural gas. These emissions standards were issued by the US Environmental Protection Agency under Section 111 of the Clean Air Act.

One set of results from the Energy Information Administration’s report shows the change in generated electricity over time, for a scenario where greenhouse gas regulations are not in place. Coal-fired electricity generation plateaus around 2040, with levels of around 200 terawatt-hours persisting until 2050 (Figure 1). For context, 200 terawatt-hours of coal-fired electricity generation produces more than 210 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually (assuming an emissions rate of 2.31 pounds per kilowatt-hour), which is almost as much as the country of Spain emitted in 2025.

Figure 1. Projections of US Coal-Fired Electricity Generation Through 2050

Figure derived from original source: US Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook 2025 report. EIA = US Energy Information Administration, AEO = Annual Energy Outlook report.

As the Trump administration continues its deregulatory efforts and advances actions to support coal, the no greenhouse gas regulation scenario will mark the path that the United States is taking. Coupled with other drivers, this change in the US energy trajectory will lead to continued emissions of greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants from coal-fired power plants. A changing trajectory for coal-fired electricity generation also has impacts on grid reliability, energy prices, communities that host mines and power plants, and the trajectory of other fuels in the electricity generation mix.

The Trump Administration Wants More Coal-Fired Electricity Generation

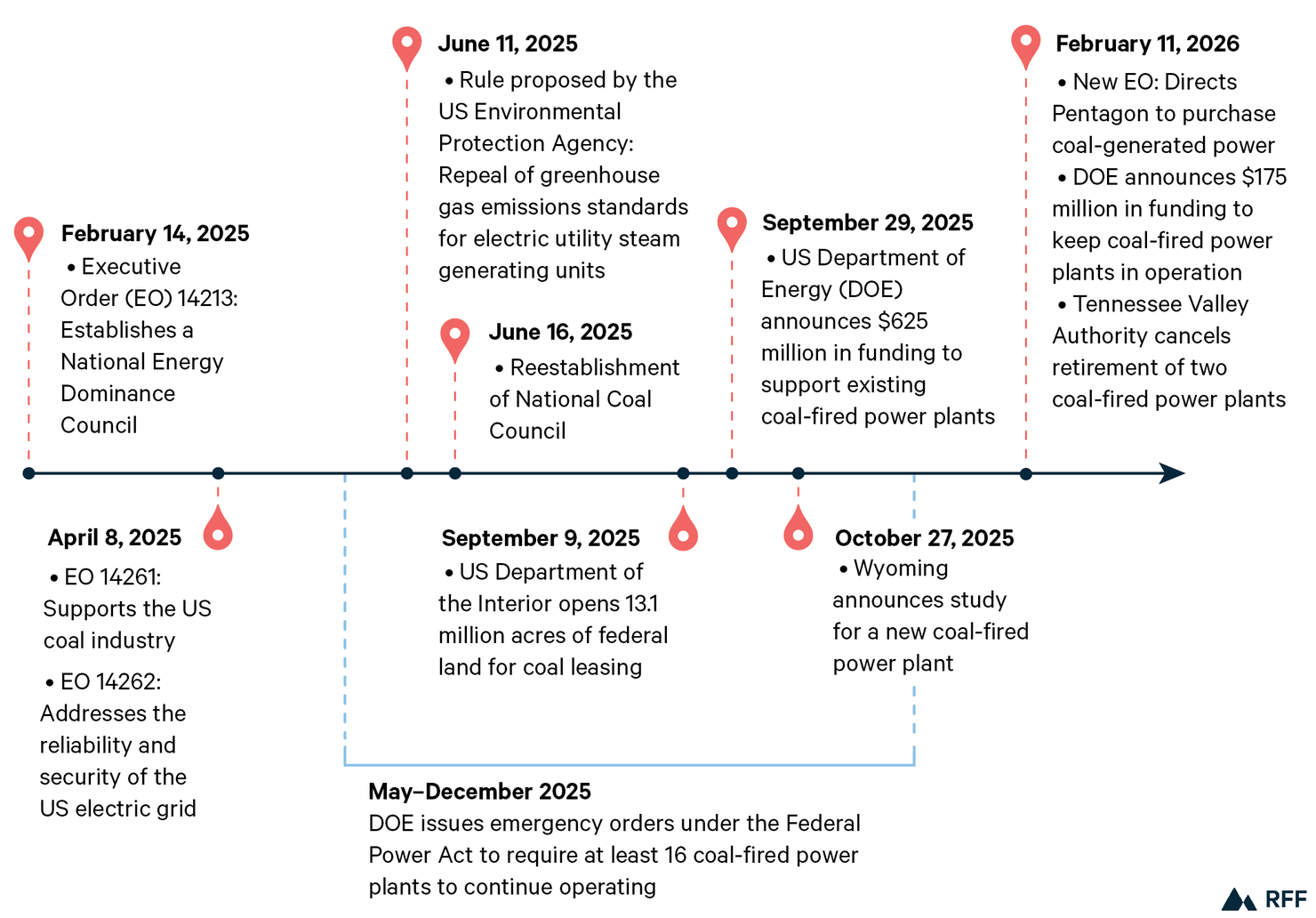

In its early days last year, the second Trump administration issued several executive orders that signaled a focus on revitalizing coal. With their emphases on traditional fossil fuels and coal utilization for electricity generation, Executive Orders 14261 and 14262, signed in April 2025, signal clearly that the United States is far from done with coal.

Since the publication of these executive orders, the administration has deployed a wide range of measures to halt the planned closures of existing coal-fired power plants, encourage (and in some cases force) continued generation at operating coal plants, encourage the construction of new coal-fired plants, and make new lands available for coal production. The administration issued emergency orders under section 202(c) of the Federal Power Act to require that at least 16 coal-fired units remain operational for the stated purposes of grid reliability, energy affordability, and preparedness for potential energy demand growth due to extreme weather and power needs from data centers. The administration also initiated implementation delays and rollbacks of regulations on air and water pollution that will make it easier and less costly to produce electricity using coal, encouraging increased generation at existing coal power plants. And the Trump administration has revived the National Coal Council and created the National Energy Dominance Council, which together have a clear emphasis on boosting the domestic production of coal, oil, natural gas, and nuclear energy.

Figure 2. Timeline of US Policies That Support Coal in the First Years of the Second Trump Administration

The US Department of Energy also has announced new funding to support retrofits and recommissioning of shuttered coal-fired power plants; projects to benefit rural communities with energy affordability, reliability, and resiliency; and advanced technologies to allow co-firing with other fuels such as natural gas. Already, some states like Wyoming (by far the nation’s leading coal producer) are exploring options to expand coal-powered generation, potentially with “clean” coal units, i.e., power plants that capture the carbon dioxide produced from coal combustion.

Most recently, on February 11, the Trump administration issued an additional executive order directing the Pentagon to purchase electricity from US coal-fired power plants using contracts that aim to sustain coal as a power source. And on the same day, DOE announced an additional $175 million in funding to upgrade six coal-fired power plants in Kentucky, North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia, and West Virginia. Also on that very busy day, the Tennessee Valley Authority announced it was canceling the retirements of the Kingston and Cumberland coal-fired power plants in Tennessee.

Illustrating that these efforts span all possible channels of active promotion, the Trump administration has crafted a publicity campaign for coal that enlists a cartoon mascot named Coalie.

You Can’t Always Get What You Want

Whether these actions will be enough to change the trajectory for coal in the United States remains to be seen. Despite the administration’s efforts, many hurdles are still in the way of coal-fired electricity production due to policy, legal, and market forces. Some states, like Colorado and Michigan, are challenging federal orders to keep coal-fired power plants open. State pollution standards, state renewable portfolio standards, and federal pollution regulations are still on the books. Restrictions on the purchase of coal-powered electricity, and concerns from plant operators and investors that future administrations may reverse course, pose additional challenges to continued or expanded coal-fired electricity generation.

In addition, renewable energy resources such as solar power remain competitive in many cases, and high costs could fall in the years ahead for other sources of clean firm power, such as geothermal and new nuclear power. Working in the other direction, domestic natural gas prices are projected to rise, making coal less expensive in comparison but adding planning uncertainty because natural gas prices are volatile.

The fundamentals of coal economics have not changed, and wishing for more coal will not make it so if the economic incentives are not there. Many operational coal plants are at or nearing the end of their economic lifespan under current regulatory and economic conditions. Building new coal-fired plants or keeping older plants operational and compliant with environmental regulations requires investments that will not realize returns for years—well after the Trump administration has ended. Option theory suggests that in the face of regulatory uncertainty at both the federal and state levels, firms may delay capital-intensive investments in coal-fired power plants, even if those investments have a profitable expected value.

In short, the political and economic risks of making large investments in new or existing coal-fired power plants are enormous. The administration’s actions are unlikely to drive immediate large capital investments in coal. The fundamental economics and negative environmental impacts of coal place this fossil fuel in a precarious position as part of a long-term energy solution.

At the same time, the administration’s actions, coupled with the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, are limiting investment in other sources of power (e.g., solar energy and battery storage) that are more modular and can be built more quickly than coal-fired power plants. These newer technologies and renewable energy sources could mitigate the very challenges the administration purports to address related to rising energy demands, reliability, affordability, and resilience to extreme weather.

We’ll see if the Coalie campaign does much to persuade the American public. Just outside the frame of this googly-eyed cartoon are smokestacks emitting air pollutants, water declining in quality, and injured miners. The advantages of a policy action don’t mean much without equally considering its disadvantages.

But What If Coal-Fired Electricity Generation Rises?

Although the prospects are limited for major investments in new coal-fired power plants, the Trump administration’s policies appear likely to maintain at least existing capacity, and thus slow coal’s decline.

To understand the implications of the slew of new policies that bolster coal as an energy source, economists need to assess the full range of impacts that will result from changing the trajectory of coal, including potential impacts on local economies and communities; state, regional, and national electricity prices; greenhouse gas emissions; and air and water pollution. Further work can help inform decisionmakers at multiple levels of governance as they consider their responses to the administration’s efforts. Careful analysis of the costs and benefits of the change in trajectory, both in aggregate and in specific locations, can reveal trade-offs or synergies that can increase net benefits or result in unanticipated societal costs.

Some research questions that economists should consider:

- What is the impact of the change in coal’s trajectory on the US electricity sector, including on the mix of fuels used for power generation, electricity prices, and emissions of greenhouse gases and conventional air pollutants?

- How does regulatory uncertainty affect electric utilities and their retirement plans for coal-fired plants, and does this uncertainty affect investment in other sources of baseload power (i.e., power that’s available to meet consistent levels of demand)?

- How will continued emissions from coal-fired power plants affect climate change, air quality, and public health, and what is the economic value of those impacts?

- What are the economic impacts of the change in coal’s trajectory for the coal-mining industry, owners of coal-fired power plants, and communities that host these power plants?

- How will the changes in location-specific impacts on air and water quality, economies, and energy affordability affect different communities, and either alleviate or exacerbate inequities?

- How can state actions or existing federal policies limit the environmental and health impacts on local populations?

- How do the costs related to increased emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollution compare with the benefits of continued or increased coal generation at national and local scales?

As we follow the rapid succession of executive orders, empaneled commissions and councils, proposed regulations (and deregulation), and changes in federal funding, we will be looking for opportunities to address these and other emerging questions.

For more timely insights about developments in environmental and energy policy, browse the If/Then series.