The Greenhouse Gas Protocol update isn’t about improving the accuracy of greenhouse gas accounting, but it might have a significant impact on emissions.

Updates to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol’s Accounting Standards

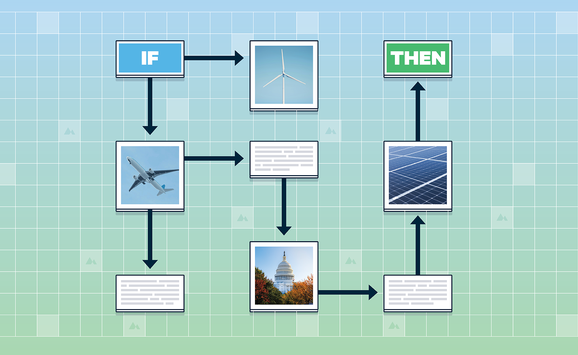

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol, an organization that determines the methodology by which companies voluntarily report their greenhouse gas emissions, has proposed changes to its greenhouse gas accounting standards. These blog posts reflect on the revisions and what they could mean for companies, greenhouse gas emissions, and clean energy investments.

- Is Accuracy the Right Criterion for Updating Greenhouse Gas Accounting Standards?

- How Could Changes to Corporate Greenhouse Gas Reporting Affect Emissions?

- How Will Changes to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol Affect Long-Term Contracts?

- How Will Changes to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol Affect Short-Term Markets?

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP), the entity which manages the accounting system that forms the basis for how most companies report their greenhouse gas emissions, is in the process of updating its guidance. This revision tackles “Scope 2” emissions, the part of the protocol which attributes emissions from electricity and heat generation across electricity consumers. The Clean Energy Buyers Association estimates that as much as 41 percent of all investment in renewable energy in the United States between 2014 and 2024 was driven by corporate buyers, most of which use the GHGP, so this update is a big deal.

In conjunction with the start of the public consultation period on the guidance, the GHGP has begun to release a series of blog posts to explain the proposed changes and the principles underlying the updates. In particular, the blog posts announce how the “changes … prioritize accuracy, greater transparency and … more comparability.” These are all laudable goals, but focusing on accuracy reflects a misunderstanding of how accounting works and what it accomplishes.

While there are legitimate bases for the proposed changes, inaccuracy isn’t really one of them. In fact, greenhouse gas accounting doesn’t measure emissions at all. Instead, as I will describe, it allocates them. The actual emissions are then determined by a complex set of incentives related to how this allocation to end-uses is done. How emissions are allocated is a policy choice. Accuracy is not only inapposite; it is a red herring. It’s far from clear what it would mean for one accounting standard to be more accurate than another.

The focus, instead, should be on the policy decisions and intentional definitions of categories and how emissions are distributed among the accounted entities. These incentives and how they translate to emissions outcomes, along with other characteristics such as implementability and complexity, are the appropriate criteria for examining the GHGP revisions.

What Is Attributional Accounting?

The world of emissions accounting is divided into two major categories: attributional accounting and consequential accounting. Attributional accounting attributes a set of emissions (such as all electricity emissions) to corporations or products, while consequential accounting attempts to measure the actual change in emissions due to some sort of intervention (such as building a data center).

The GHGP explicitly states that Scope 2 corporate accounting is attributional. In a September blog post, the updaters write, “Importantly, this work remains firmly grounded in an attributional, value-chain inventory …” The idea behind attributional accounting is to look at the supply chain of a company and account for the emissions from the production of the products in that supply chain. Given its prominence, electricity consumption is distinguished as the largest part of Scope 2. In addition to Scope 2, the protocol includes other types of indirect emissions, upstream and downstream, as part of Scope 3. Such Scope 3 emissions could include things such as business travel and emissions from the use of fuels produced by a company. Direct emissions from a facility owned by a company are Scope 1.

The Trouble with Electricity

Unlike many goods, electricity cannot be tracked from its generation to its consumption. I discuss this fact in more detail in a January 2025 blog post. Given this challenge, the GHGP has two methods to account for electricity emissions. This first is “location based,” where an electricity consumer uses a local average emissions rate for electricity to calculate their Scope 2 emissions. Under this method, the only ways a company can reduce its Scope 2 emissions are either to change where it consumes electricity or to reduce its electricity consumption.

Because this is a limited set of options, the GHGP also offers a “market-based” method. The market-based method uses what is called a “book-and-claim” system. In this system, emissions-free (or “clean”) generation of electricity is distinguished from other forms of electricity generation. Each unit of clean electricity produced also produces something called an energy attribute credit (or a renewable energy credit, for renewable energy), essentially a piece of paper that a company can purchase to claim that it is consuming clean electricity. This is a useful fiction, which allocates the clean electricity to consumers through a financial transaction of the certificate, but it does not mean that somebody is actually consuming clean electricity just because they bought an attribute credit.

What Does This Have to Do with Emissions?

Given that electricity cannot be tracked and the use of the book-and-claim system, we are already far afield from a straightforward quantification of emissions associated with electricity consumption. Moreover, even in situations where a facility is directly connected to a clean electricity generator, the attribution of clean electricity to that facility does not necessarily imply no increase in emissions associated with the facility.

For example, consider an existing wind farm and a new data center built next to that wind farm. If one were to disconnect that wind farm from the grid and connect the wind farm directly to the data center, the electricity consumed by the data center would be emissions free. However, that wind farm was already serving demand. By taking it off the grid, some other generation will have to serve that demand, and that generation could produce emissions. Looking at the system as a whole, emissions can go up, even as the supply chain for that data center remains clean.

The upshot here is that Scope 2 emissions accounting does not measure emissions. But if we’re not measuring emissions, the important question arises: Why are we bothering with this greenhouse gas accounting at all? The GHGP states the following reasons in its guidance:

• Identify and understand the risks and opportunities associated with emissions from purchased and consumed electricity

• Identify internal [greenhouse gas] reduction opportunities, set reduction targets, and track performance

• Engage energy suppliers and partners in [greenhouse gas] management

• Enhance stakeholder information and corporate reputation through transparent public reporting.

These are all reasonable justifications, but there is a more fundamental objective. Attributional accounting motivates companies to spend money on clean electricity. That money, transferred from consumer to producer in the purchase of the attribute credit, leads to more clean electricity—it’s just very hard to know how much.

Whither Accuracy?

Given these facts about electricity and emissions accounting, the idea of accuracy seems beside the point. If one isn’t trying to measure emissions, what does it even mean to have one accounting system be more accurate than another? Currently, an energy attribute credit can be used to say one is consuming clean electricity in any hour of the year, no matter when the credit was created. The proposed changes to the GHGP Scope 2 standard would (among other things) restrict the credit to be used in the hour and the region in which it was created. If greenhouse gas accounting were really about the consumption of clean electricity, then this restriction might make sense—one certainly can’t consume clean electricity at a different time than it was generated or if no wires connect the generator to the consumer.

But accounting isn’t about the consumption of clean electricity. Instead, it is a choice about the universe of clean electricity we want to allocate to electricity consumers: Is it a bundle of all clean electricity produced during the year, or is each hour and region kept separate? This is an incredibly consequential choice that I plan to write about more. It has implications for markets, implementation, emissions and more. It just doesn’t have much to do with accuracy.