New analysis shows that the average price on carbon emissions across the United States will likely increase due to state policy, advancing nationwide decarbonization goals.

Is US climate policy toast? In 2025, it is tempting to think so, especially as Clean Air Act regulations for greenhouse gases are being repealed, the federal government’s social cost of carbon is set to zero, many clean energy policies from the Inflation Reduction Act are disappearing, and the prospect of a national carbon price is more distant than ever.

Yet not all US climate policy is national policy. Over the years, several states have enacted legislation and set up programs aimed at curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Chief among them are the carbon prices that state policymakers have implemented in California, Washington, and an assemblage of 10 northeastern states known as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). The combined policy efforts of these 12 climate policy leaders sum to a major shift in US climate policy.

A carbon price incentivizes decarbonization by requiring polluters to pay for the carbon dioxide they emit. Economists generally view carbon prices as the most cost-effective policies for emissions reductions because they incentivize adoption of all emissions-reduction options that are less expensive than the carbon price. In general, a higher price on carbon reflects a more credible path for decarbonization, and higher revenues from the program.

So, how do state-level carbon prices contribute to the effective US average carbon price? What did policymakers do to reverse the downward trajectory of this average price?

In the United States, carbon prices are determined in emissions markets instead of through government-set fixed prices (i.e., a carbon tax). States set a limit on emissions—referred to as an emissions budget—for a given period and then distribute and auction allowances to polluters based on those budgets. Once polluters receive allowances, they can trade the allowances in a market, where the interaction of the supply and demand of allowances determines the carbon price.

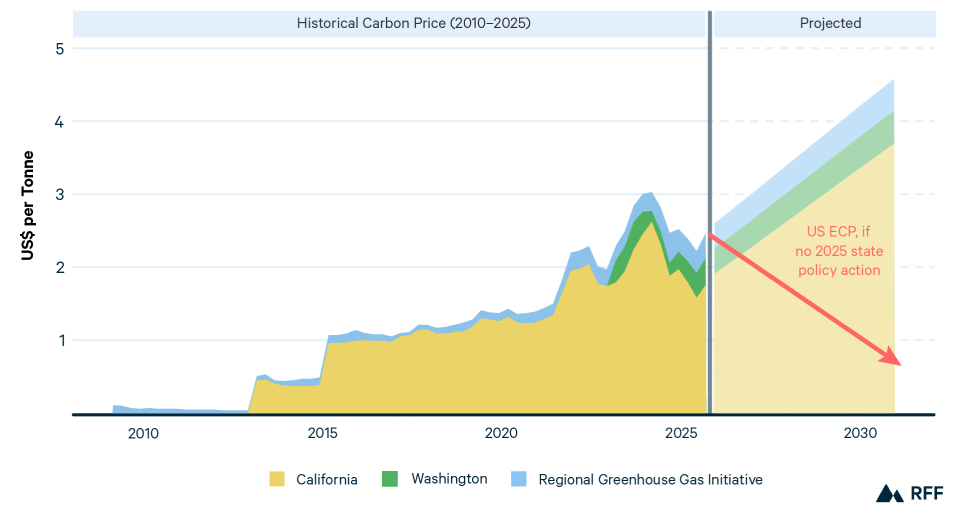

Using data on emissions and allowance budgets of the three subnational carbon pricing programs in California, Washington, and the Northeast, we can calculate the average effective price on carbon across the United States. These three markets have prices ranging from $20–$60 per ton of carbon dioxide, but since they only cover a small share of US emissions, the effective price on US carbon emissions is much lower. Our research shows that, at the end of 2024, state-level carbon pricing initiatives brought the nationwide average price of carbon dioxide emissions to $3 per ton. While $3 is modest compared to the effective global average carbon price of about $7.50 per ton, the effective US carbon price had been steadily increasing over time until this year.

Figure 1 shows each of the three markets’ contributions to the historical increase in the US carbon price over the past 15 years. At the end of 2024 and beginning of 2025, subnational carbon markets were rattled by uncertainty arising from federal attacks on state-level climate policy, dithering policy updates, and broad affordability concerns. Without state action, California’s market may have ended after 2030, and carbon prices in the other two markets could have continued on lower price paths (see the red dashed line).

However, all three markets underwent major reforms that restored market confidence. These reforms set the state-level carbon prices on track to bring the average US price above $4 by 2030. So, what did policymakers do to reverse this downward price trajectory?

Figure 1. US Effective Carbon Price (ECP) Partitioned by Subnational Markets (2025 US$)

Source: World Carbon Pricing Database

Methodology: Quarterly auction prices are multiplied by the US share of emissions covered by these programs and inflation adjusted to 2025 Q2 US$ using GDP deflators. Projections for Washington and RGGI follow a 5 percent annual increase of current prices (following the cost containment price paths they are on today). California projections are based on the California Air Resources Board 2024 Standard Regulatory Impact Assessment price trajectory, which goes into full effect by 2030 with a linear interpolation until then.

Across all states with carbon pricing, two objectives for recent policy action are clear:

- Provide long-term policy certainty that these carbon prices are going to drive emissions reductions through tighter emissions budgets.

- Neutralize short-term political opposition to these programs by making carbon prices solutions to—not drivers of—affordability concerns, and by improving cost-containment measures.

Washington State arguably was the first market to take action after a ballot measure to repeal its program failed in the 2024 election. In the months before voters decided the program’s fate, demand for allowances was low because polluters didn’t know if they’d need them in 2025, should the ballot measure succeed. This low demand kept prices, and the associated revenues from the program, low until the measure failed. When the price in Washington began to rebound following the vote, the legislature acted fast to enhance cost-containment measures in the short run and plan for market reforms to combine its market with California’s in the long run. Revenues from the allowance auctions more than doubled due to the reinvigoration of Washington’s market.

In the midst of the passage of these reforms, the federal government singled out carbon markets in an April executive order that shook confidence that these programs would survive. Prices fell again, this time across all markets. This was a critical juncture where, if state action stalled, prices would begin to follow the red dashed line in Figure 1. Instead, the state governments leapt into action.

The 10 RGGI states finalized a long-awaited rule in July that tightened the emissions budget and improved cost-containment mechanisms. California, the largest driver of the US carbon price, reauthorized its program through 2045 in September, allowing state policymakers to return to their rulemaking process, which had faced delays over the past few years.

These policy actions were not predetermined, likely, nor obvious. The political headwinds of affordability concerns slowed action from states because of the long-standing belief that addressing climate change costs households. However, recent policy innovation began to decouple this narrative by focusing on the investments that can be made with the revenues raised by these carbon pricing programs. For example, California’s reauthorized program now redirects carbon pricing revenues to refunds for household electricity bills during times of the year with the highest electricity costs.

In that same law, California followed Washington’s lead in rebranding its cap-and-trade program as cap and invest. While “trade” emphasizes the cost efficiency that markets provide in addressing climate policy, “invest” emphasizes the revenues that can be invested into the economy, businesses, and households. This strategic shift in how to use program revenues builds a broader political constituency around climate action while retaining the cost-effectiveness of carbon pricing.

Given this framing shift, it becomes clear that Figure 1 also suggests that political appetite for climate policy was replaced by concerns about its affordability. Households might observe a rising price on pollution and decide that curbing it isn’t worthwhile if polluters pass the costs on to them. Responding to these concerns, policymakers delayed tightening carbon budgets. With recent reforms, not only are polluters facing higher incentives for decarbonization, but households directly receive more of the benefits from higher carbon prices. Meanwhile, the industries facing the carbon price are investing in technologies to reduce their carbon intensity.

In total, the carbon pricing programs in California, Washington, and RGGI cover about 10 percent of US emissions, even though the economies in these states represent a larger share of the national economy. These policies alone are insufficient for US economy-wide decarbonization aligned with climate targets under the Paris Agreement. However, at a time when the US government is reversing national climate policy, state carbon prices serve as meaningful backstops to continue progress until federal efforts rekindle. For now, the major driver of US climate action isn’t federal action—it’s federalism.