Even as climate change drives increasing physical and transition risks for the financial sector and economy, the sector has pulled back on addressing climate-related financial risks. Several outcomes, outlined here, may be likely to arise as a result.

The US financial sector shows fundamental tension with respect to climate-related financial risks. On one hand, the economic and financial risks from climate change are growing, and a traditional risk-management perspective provides a coherent case for financial institutions and supervisors to monitor and manage these risks. At the same time, however, the financial sector is pulling back in terms of how climate-related financial risks are discussed and addressed. This blog post describes that tension and considers how the US financial sector may evolve in response.

The Fundamental Tension

A broad array of data shows that the economic and financial impact of climate change is growing in response to both physical and transition risk drivers. In terms of physical risks, natural disasters are rising globally, the number of billion-dollar disasters is trending upward in the United States, and global insured losses from natural catastrophes have been growing 5 to 7 percent annually in real terms. While the economic and financial losses from these physical events reflect a range of factors such as greater economic development in high-risk areas and rising building costs, climate change is a growing contributor.

In terms of transition risks, policy, sentiment, technology, and the structure of the economy continue to evolve. For example, the share of the global economy subject to carbon prices and emissions trading systems is rising, the price of renewables relative to fossil fuels is falling, and the renewable energy sector is growing. Policy shifts, particularly with the passage and reversal of the Inflation Reduction Act, drive economic outcomes and increase uncertainty.

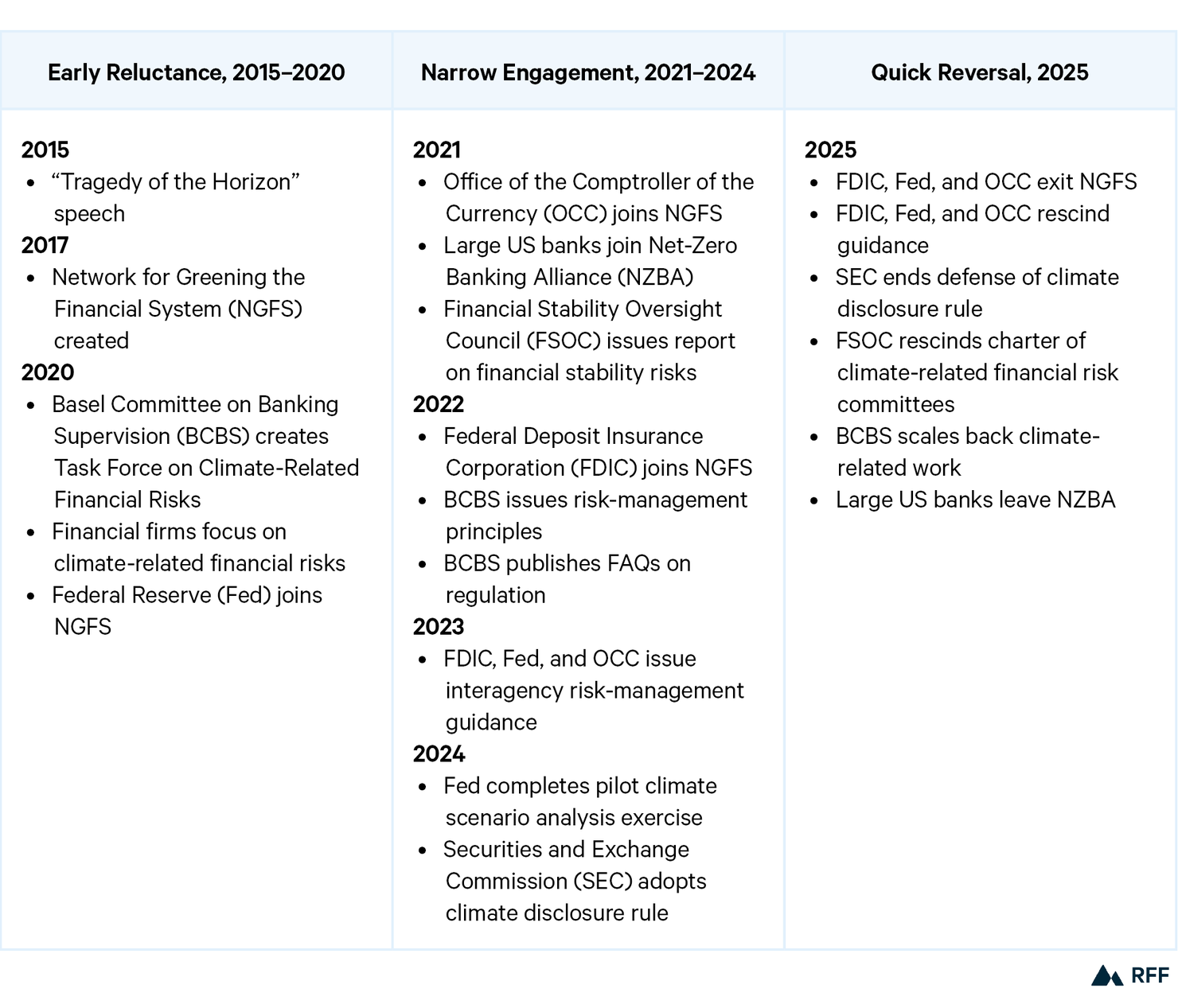

In the US financial sector, attention to these risk drivers over the past decade can be broken into three phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evolving Focus on Climate-Related Financial Risks by US Financial Sector

2015–2020: Early Reluctance. Global central banks and supervisors entered the climate space, motivated by then–Bank of England Governor Mark Carney’s famous “tragedy of the horizon” speech in 2015. The Network for Greening the Financial System was created shortly after, in 2017, by eight central banks and supervisory authorities. The US federal bank regulators (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Federal Reserve, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) began to contribute to international work on climate-related financial risks through the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, while financial firms began to identify climate-related risks as financial risks. The Federal Reserve was the first federal bank regulator to join the Network for Greening the Financial System.

2021–2024: Narrow Engagement. US regulators became increasingly active as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency joined the Network for Greening the Financial System. The federal bank regulators contributed to the supervisory work and regulatory work of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and issued interagency risk-management guidance for large banks. The Financial Stability Oversight Council issued a report on financial stability risks, and the Federal Reserve completed a pilot climate scenario analysis exercise that focused on building capacity to better understand these risks. The Securities and Exchange Commission adopted a climate-related disclosure rule for investors. An important guardrail for bank regulators was to take a risk-management perspective and not engage in climate policymaking through bank supervision and regulation. In the private sector, many large US banks joined the Net-Zero Banking Alliance in 2021 and published climate-related strategies and disclosure documents.

2025: Quick Reversal. Beginning in 2025, US regulators quickly pulled back as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Federal Reserve, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency exited the Network for Greening the Financial System and rescinded the interagency guidance, while the Securities and Exchange Commission voted to end defense of its climate disclosure rules. The Financial Stability Oversight Council rescinded the charter of two climate-related committees and warned of mission drift that could lead to an excessive focus on climate risk and the effective debanking of certain industries. At the same time, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s oversight group narrowed the remit of climate-related work. Large US banks exited the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, which subsequently ended activities, and generally reduced public discussions about climate-related financial risks.

This quick reversal was surprising given the growing risks and purpose of supervision. The standard explanation for bank regulation and supervision is that market failures (such as information asymmetries and externalities) and the resulting institutional responses (such as deposit insurance and lender-of-last-resort responsibilities) encourage banks to take excess risks from society’s perspective. As a result, governments have developed regulations (such as minimum capital standards) and supervision (including broad risk-management expectations) to curb this excess risk-taking. Current supervisory expectations in the United States include both general risk-management standards and risk-specific elements for particular risks such as interest rate risk or cyber threats. Given distinctive attributes of climate-related financial risks such as the secular trend in physical risks, the deep uncertainty about the timing of economic and financial impacts, and the need for new models, data, and expertise, a risk-specific focus seems useful in the context of climate-related risk drivers.

What Happens Next?

Given this fundamental tension over climate-related financial risks, what happens next? Banks will need to continue to work with their clients, pursue opportunities, and manage risks despite uncertainty around the impact of climate change and the broader policy environment, while supervisors will need to ensure that banks manage all material risks effectively. From a strictly positive (not normative) perspective, four outcomes seem likely.

Language Will Change, But Actions Matter More

In prior years, observers of the financial sector were concerned with the potential for “greenwashing,” such that firms might overstate their ambition and action with respect to climate change. More recently, this phenomenon has shifted to “greenhushing,” whereby firms might understate their actual climate-related activities to avoid unwanted external scrutiny. As one example, a simple word count of the word “climate” in the annual reports of large US banks shows the same increasing and then decreasing pattern as discussed above.

Ultimately, words and actions will converge, so stakeholders will have a more clear and transparent understanding of the actual risks to financial firms and the specific steps being taken to manage those risks. In the interim, however, it seems more useful to watch what the financial sector is actually doing (e.g., loan pricing, evaluating concentration limits, underwriting decisions, hiring, and setting strategy), rather than what the sector is saying. Looking forward, it would be useful to develop metrics related to risk-management activities among banks, including inputs (e.g., expenditures on data or personnel) and business-level decisions (e.g., pricing or strategic shifts that reflect climate-related drivers).

Focus Will Shift to Physical Risks and Adaptation

The US financial sector will focus increasingly on physical risk relative to transition risk. Physical risks are more salient in the short run; consider the estimated $76 billion–$131 billion in property loss and capital loss from the Los Angeles wildfires in 2025 and the $79 billion and $34 billion of total costs in 2024 from Hurricanes Helene and Milton, respectively. Swiss Re reports nearly $140 billion in global insured losses from natural catastrophes in 2024. Banks of all sizes have long managed natural disasters, but it seems reasonable to enhance risk-management capacity such as greater use of catastrophe models to reflect the growing impact and distinctive attributes of physical risk drivers.

By contrast, transition risks are likely to be downplayed. Particularly for those associated with reallocation of economic activity across sectors or regions, transition risks seem much more politically fraught with discussions of winners and losers and the potential for political reactions. Financial institutions will continue to work with clients and manage risk, but likely with a greater emphasis on supporting clients’ financial and strategic needs and not under the banner of transition-risk management.

State and Local Actions Will Diverge from Federal Actions

As government entities assess the impacts of climate change, the approach of state and local entities and federal entities will continue to diverge in the short run. The impacts of climate change, particularly from physical risks, are a local phenomenon, and state and local entities are taking steps to address these issues.

As of December 2025, 25 states and districts had statewide adaptation plans in place or underway that include a wide range of proactive investments to build resilience, e.g., improved building codes, shoreline management, altering the built environment, and urban forestry. As examples, the 2024 State Flood Plan in Texas is designed to identify existing risks and provides recommendations for preventing an increase in flood risks, and the 2026–2027 Statewide Flooding and Sea Level Rise Resilience Plan in Florida identifies projects that address risks of flooding and sea level rise. It remains to be seen, however, how these plans translate into action and, consistent with the points above, neither plan directly attributes changes in risk to climate change.

By contrast, federal actors are retreating from taking forward-looking, preventive steps. As mentioned above, the federal banking regulators have exited the Network for Greening the Financial System, removed interagency guidance, and are talking less about climate-related financial risks. For example, the Federal Reserve discussed its proactive approach to the financial risks of climate from a financial stability perspective in 2021 and from a supervisory and regulatory perspective in 2022. By contrast, federal banking agencies now believe the risk-management principles are not necessary and are concerned that these climate-related principles could distract from the management of other risks. Similarly, the US Office of Management and Budget issued a report to identify climate-related risks for federal programs, review federal agency adaptation plans, and estimate the benefits from investments in climate mitigation—but this report has since been removed. Federal regulators likely will continue to take reactive steps after natural disasters occur.

Private Business Objectives Will Continue to Be Separate from Social Decarbonization Goals

Discussions of the link between climate change and banks often have considered two related forces: the impact that climate change has on a bank (e.g., new risks or opportunities) and the impact that a bank can have on climate change itself (e.g., through financing fossil fuels or renewable energy). Going forward, the financial sector will focus on the risks and opportunities from climate change, rather than its own impact on climate change.

Corporations, including financial firms, have responsibilities to multiple stakeholders, such as customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and investors. These obligations do not necessarily include a specific responsibility to internalize the fundamental carbon externality that drives climate change, but the financial sector was seen as a lever to change the real economy to achieve public policy objectives such as supporting the transition to a net-zero economy. From an economic perspective, finance is an intermediate input to production, like other inputs such as raw materials, and why should finance in particular be held responsible for internalizing the carbon externality? Financial firms will continue to work with their clients to identify opportunities and manage risks related to climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy, with less emphasis on broader decarbonization or transition goals.

Conclusions

The future evolution of the link between climate change and the US financial sector will depend on many factors—the pace and severity of climate-related shocks, technology shifts, behavioral changes, and policy decisions—so, the path is subject to considerable uncertainty. This uncertainty creates challenges for the financial sector, but also opportunities for policy-relevant research.

Insurance market dynamics is an area of active research, including the drivers of changes in pricing, availability, and coverage (particularly in high-risk areas). Work on what makes certain locations or activities uninsurable and how the insurance industry is responding seems particularly important. The impact of indirect effects such as damage to critical infrastructure or disruptions to supply chains is a second area in which more work is needed. A third area is to develop a deeper understanding of how climate-related shocks impact the fiscal position of the federal government or state and local governments, e.g., tax revenue, disaster spending, and contingent liabilities.

A common theme across these three topics is that they address the fundamental questions of how big the economic and financial impact from climate-related shocks will be and who ultimately bears the losses. While it seems clear that the impact will continue to rise, the ultimate allocation of the damage could vary widely across many participants, such as insurers, reinsurers, banks, homeowners, investors, state and local governments, and the federal government—depending on the nature of the shocks, institutional arrangements, and policy responses. Understanding this “flow of risk” through the financial sector is essential to understanding, and ultimately managing, climate-related financial risks.