Recent federal actions to support the burgeoning US critical minerals industry lack a clear strategy to address national security and short-term priorities.

Disturbed by the market power of Chinese companies in the production of raw materials—a position which gives China strategic advantages in trade negotiations—the Trump administration promised significant investments in the minerals sector. Since July, the federal government has been making headlines by directly investing in firms that produce the materials required for several critical technologies. The administration has even taken ownership positions, or equity stakes, in several firms and holds warrants in others. It has also expanded its financing capabilities, levied tariffs, and even guaranteed a price floor to a company producing rare earth oxides and magnets in the United States.

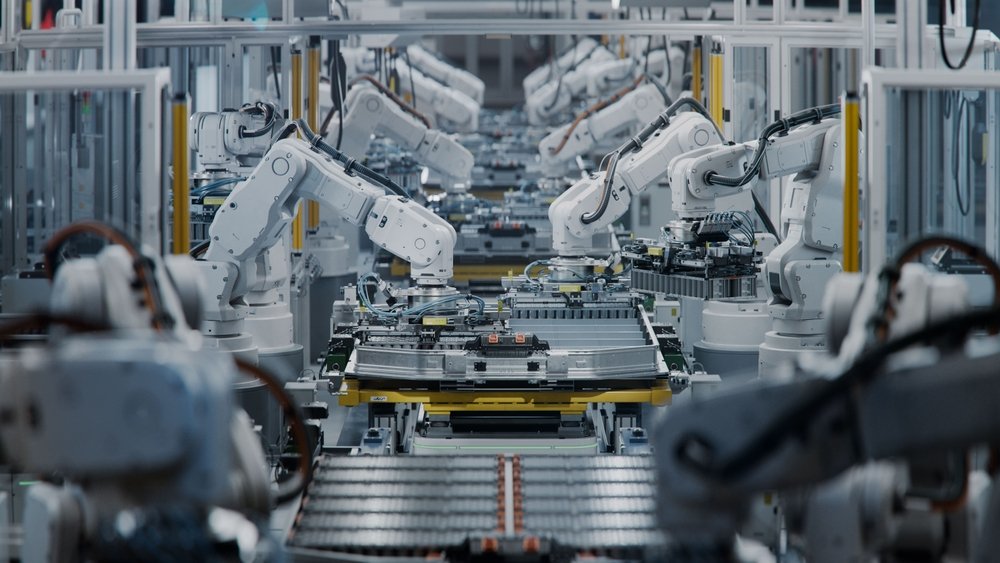

While the Trump administration is moving fast and breaking precedent, its actions reveal inconsistencies across objectives; lack a clear prioritization framework; and raise several economic questions about long-run durability, competitiveness, and cost-effectiveness. Below, we take stock of recent federal actions as the industry awaits sustained price stabilization or demand signals for critical minerals produced outside of China. Mining and minerals processing are highly capital-intensive industries; given current market conditions, recent efforts to increase domestic critical minerals capacity have yet to indicate that newly formed operations can sustainably compete with their Chinese counterparts.

Many Recent Interventions Do Not Focus on Short-Term, Immediate Defense Needs

A White House spokesperson recently characterized the federal government’s equity investments in critical mineral companies as “targeted” and designed to encourage further investment by the private sector. However, no clear or consistent underlying criteria have been evident in the investment decisions the administration has made over the past several months.

So far, the administration has made direct investments in a pre-permitted project that focuses on the extraction of base metals and precious metals; a lithium extraction and processing project (as part of a joint venture with an electric vehicle manufacturer); two permanent magnet fabrication plants; and refining facilities for rare earths, gold, silver, gallium, zinc, and more. Including the recently announced Export-Import Bank financing, the set of potentially supported companies expands further. We are also seeing interventions through US-backed investment firms: the US Development Finance Corporation recently complemented its stake in TechMet, whose projects span four continents, by capitalizing Orion Resource Partners with Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund, ADQ.

Taken together, these actions do not suggest a clearly targeted strategy honed to short-term, immediate defense needs. We do not mean to suggest that rationale has not driven this executive decisionmaking, but rather that the set of investments reflects an effort to address bottlenecks across vastly different critical mineral supply chains simultaneously.

More fundamentally, the intent behind this mix of interventions is unclear. For instance, if the immediate demands of national security alone justify heavy-handed government intervention, then limited public capital and capacity would not be directed toward a pre-permitted project for base and precious metals, which will likely take many years to begin production. Similarly, an investment in a lithium mine structured around electric vehicle battery production does not seem to match the administration’s priorities, given that its recent policy reversals will likely slow electric vehicle adoption rates.

On the other hand, rare earth magnets represent a particularly immediate vulnerability. These magnets are ubiquitous in advanced technologies and originate from highly opaque supply chains. Further, certain processed materials that are necessary to fabricate these magnets are produced virtually nowhere outside Beijing’s jurisdiction. The production of magnets is an area where more deliberate targeting is warranted, particularly for defense applications.

In a November blog post, we argued that policies to onshore critical mineral supply should prioritize projects that exhibit cost-competitiveness, strong technical and workforce readiness, and community support to ensure success. The Trump administration has supported projects in friendly nations, which is necessary for resilience—particularly in the short run—but domestic capacity is still a priority. Ensuring that domestic investment focuses on supply chains for immediate needs would bring clarity to the entire effort. Certain segments of the rare earth magnet supply chain present this need, though it will be immensely costly to build out new capacity, and the government will not solve the coordination problem by taking public ownership alone.

Equity Stakes Alone Do Not Shift Project Economics

It is one thing for the federal government to mobilize public capital and attract Wall Street investors, but another thing completely to shift the underlying economics of a domestic industry that has been in secular decline. The government taking equity stakes in a corporation does not guarantee success—either for the invested company or for the broader domestic industry.

However, this past July, the administration made an intervention that appeared to transform the prospects of MP Materials, the operator of the storied Mountain Pass Rare Earth Mine of San Bernardino County, California. The US Department of Defense is now the company’s largest shareholder and has committed to paying far above recent market prices for the production of light rare earth oxides. If successful, the company will produce up to 10,000 metric tons of permanent magnets annually, 70 percent of which the Department of Defense has committed to buy. (Importantly, given that the company claims to be able to rapidly scale up extraction, and the financial security provided by the offtake agreement and price floor, this deal represents the one investment over the past year that matched the urgency and risk of the need with the scale and commitment of investment.) Yet the total price tag of this federal support remains to be seen—recent attempts to build rare earth processing capacity outside China have been plagued by cost overruns.

By contrast, the effect of government involvement in Lithium Americas may not prove to be as transformative for the company. The US Department of Energy now has a 5 percent equity stake in the company, signaling a strong interest in Lithium Americas’ success and an expectation that federal funds loaned to the company will yield profits for the American public. However, at current market prices, Lithium Americas does not appear competitive, indicating downside risk for the public. Further complicating the operation’s prospects, Lithium Americas’ Thacker Pass project is a joint venture with General Motors, which invested in the mine to supply lithium for its line of electric vehicles.

It is one thing for the federal government to mobilize public capital and attract Wall Street investors, but another thing completely to shift the underlying economics of a domestic industry that has been in secular decline.

Federal policy changes on electric vehicles have weakened demand for US-produced lithium. As stated above, electric vehicle adoption will likely continue to decrease in part because of the administration’s policies. Without incentives for lithium-rich batteries produced in the United States, government equity stakes in lithium producers and processors are less likely to be transformative for firms and leave the government more exposed to downside risk. Indeed, when the US Department of Energy took the equity stake in Lithium Americas, General Motors partially backed out of its offtake agreement, likely due to its own reversal on future electric vehicle offerings.

Fundamentally, the power of the MP Materials agreement is the price-support mechanism and the government’s 10-year commitment to buy the company’s products. No such protection against depressed mineral prices has been afforded to Lithium Americas. Without a favorable price environment, efforts to geographically diversify critical mineral processing and refining capacity will face formidable barriers. Excluding Chinese producers from supply chains, as the Department of Defense is doing, will not singularly create conditions for non-Chinese producers to sustain their operations. Public procurement requirements are certainly part of the puzzle, but without action on prices, new projects simply may not pencil out, especially for heavy rare earths.

Some Experts Question the Portfolio of Supported Projects

To understand how these interventions are perceived across the critical minerals sector, we interviewed industry experts, academics, and company representatives on how new policy approaches could impact supply chain dynamics.

Experts broadly agreed on the project-finance challenges facing mining and minerals processing, with investors discouraged by systemic uncertainty over payback periods and long-term mineral demand. Most experts agreed that US interventions like price floors, offtake agreements, and equity stakes are likely to continue in an environment of volatile and depressed prices, even though these policies can be extremely expensive for the government. We also observed consensus among experts that stable downstream market demand is crucial for offtake agreements and price-stabilization efforts to succeed.

While interviewees generally viewed the deal with MP Materials as a national security priority and therefore a necessity, the deals struck with other projects—such as Lithium Americas, Trilogy Metals, and Vulcan Elements—prompted more questions. Some voiced concern over whether the decisionmaking was based on robust techno-economic and environmental impact analyses, if a compromise was struck on investing in more strategic projects in favor of immediate solutions, and the connections between the administration and selected projects.

Experts also agreed on the need for bilateral and multilateral international agreements, especially with allies like Australia and Canada, as the United States has limited mineral-processing capabilities. Despite consensus on the need for such frameworks, some emphasized that international deals must not act as substitutes for supporting domestic processing capacity in limited cases.

Several experts noted the need to strengthen federal technical capacity and argued for reviving the functions that once were carried out by the US Bureau of Mines, or creating a modern counterpart, noting that continued federal intervention without such technical expertise could lead to inefficiencies in public-private partnerships. However, others cautioned that reviving the bureau might politicize decisionmaking and duplicate the work of existing research arms such as the National Laboratories and the Critical Minerals Innovation Hub.

Interventions Are Likely to Continue

Chinese export controls on rare earth elements have eased for now, providing relief to automakers and the European effort to supply Ukraine’s defense against Russian forces. An October RFF issue brief notes that this is in line with game theory, which indicates that the most likely scenario is not a future “long-term withdrawal of supply” by China, but rather the continued limited withdrawal of supply from the market, better characterized by “a calculated, strategic play in a repeated game.”

Even so, US government interventions are likely to continue, at least until officials believe the defense-industrial base has a sufficient supply of engineered materials originating outside of China, and potentially other jurisdictions where Chinese companies dominate operations. Though the Trump administration has declared import dependence in certain critical minerals as a “national emergency,” officials haven’t yet taken coordinated multilateral action on price floors or made major strategic demand-side interventions, which leverage the power of the consumer market.

Equity stakes are on the table, but interventions on a company-by-company basis do little to contest China’s role as the world’s “sole manufacturing superpower.” Without a multilateral and targeted strategy, reducing the country’s market power for industries in which Chinese firms have a comparative advantage is a tall order. The political will appears to have materialized for supporting the production of rare earth magnets, but strategy must adapt to match the unique circumstances and use cases for the myriad other minerals and derivative products the government considers to be critical materials.