President Joe Biden’s proposed fuel economy standards are more ambitious than those of his predecessors, but the regulations might only modestly reduce emissions from passenger vehicles.

Because of concern over the impacts of fossil fuels and emissions on the climate, the United States and other countries are committed to a transition away from dependence on oil in the transportation sector. As part of that transition, the Biden administration recently has proposed new, stricter vehicle fuel economy standards for light-duty vehicles (cars, SUVs, and small trucks) through the model year 2026. Auto manufacturers have long been subject to fuel economy and emissions standards for the vehicles they sell in the United States, and these proposed revisions effectively will undo the Trump administration’s efforts to weaken the standards. Still, it remains unclear how much the proposed standards will help the Biden administration achieve its ambitious greenhouse gas reduction goals.

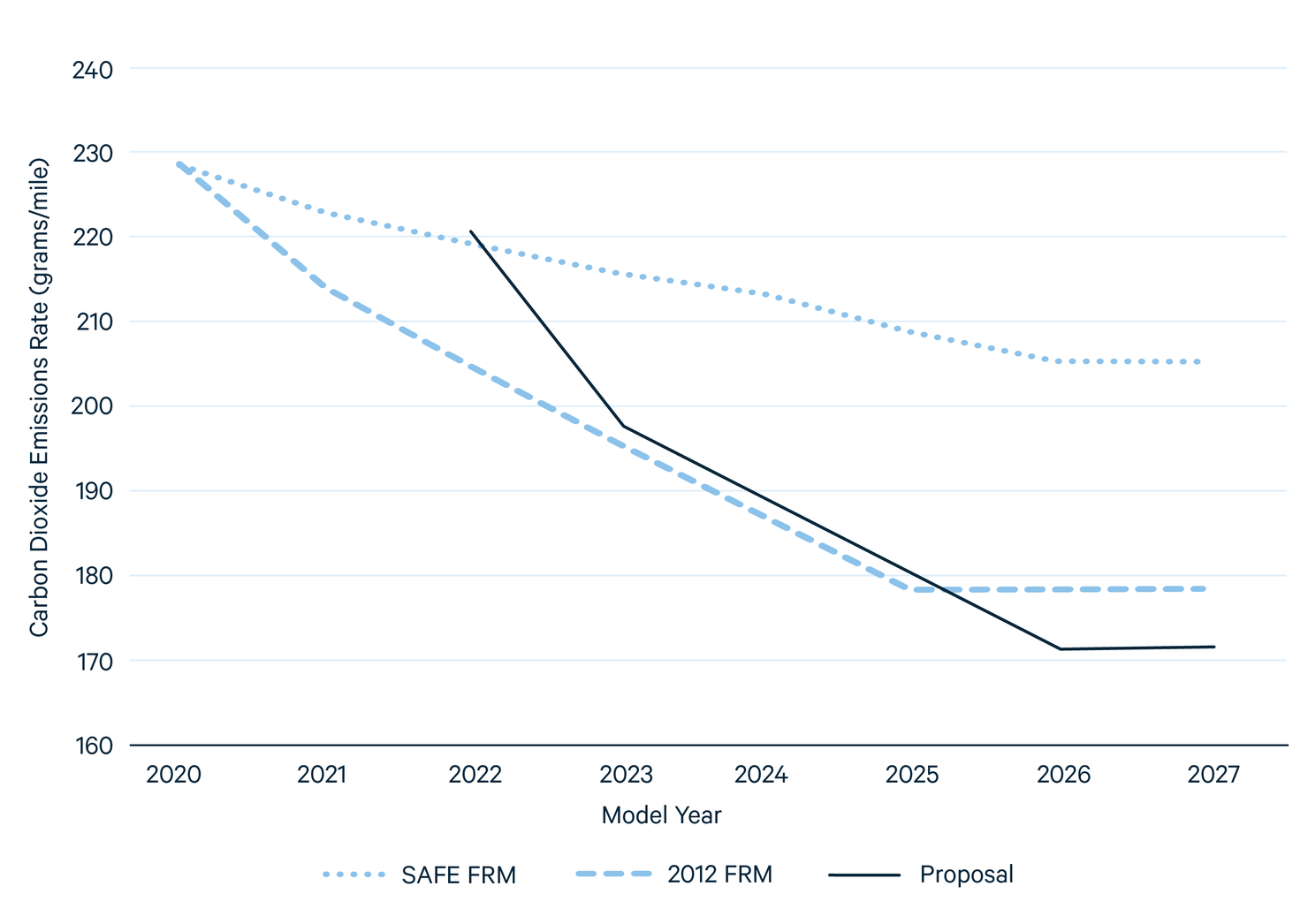

For context, Figure 1 compares three sets of greenhouse gas standards for new cars: the Obama-era standards that were finalized in 2012 and were designed to run through 2025 (“2012 FRM” indicates the final rulemaking, or FRM, from 2012); the Trump-era standards that were finalized in 2020 (“SAFE FRM” indicates the final rulemaking for the Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient, or SAFE, Vehicles Rule); and Biden’s proposed standards (“Proposal”). By 2026, the Trump standards would have resulted in emissions rates about 15 percent higher than the Obama standards. By comparison, the Biden proposal gets the market back to the Obama standards by 2025 and then results in an even lower emissions rate than the Obama standards in 2026 and after.

Figure 1. Emissions Rates of New Passenger Cars under Different Administrations

“SAFE FRM”: final rulemaking for the Trump-era standards Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient, or SAFE, Vehicles Rule finalized in 2020. “2012 FRM”: final rulemaking (FRM) from the Obama-era standards finalized in 2012 and designed to run through 2025. “Proposal”: Biden’s proposed standards. Source: Revised 2023 and Later Model Year Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards – Regulatory Impact Analysis

Importantly, even though Biden’s proposed standards will reduce new vehicle emissions rates, the reduction in total emissions from the light-duty fleet is likely to be small over the next five years.

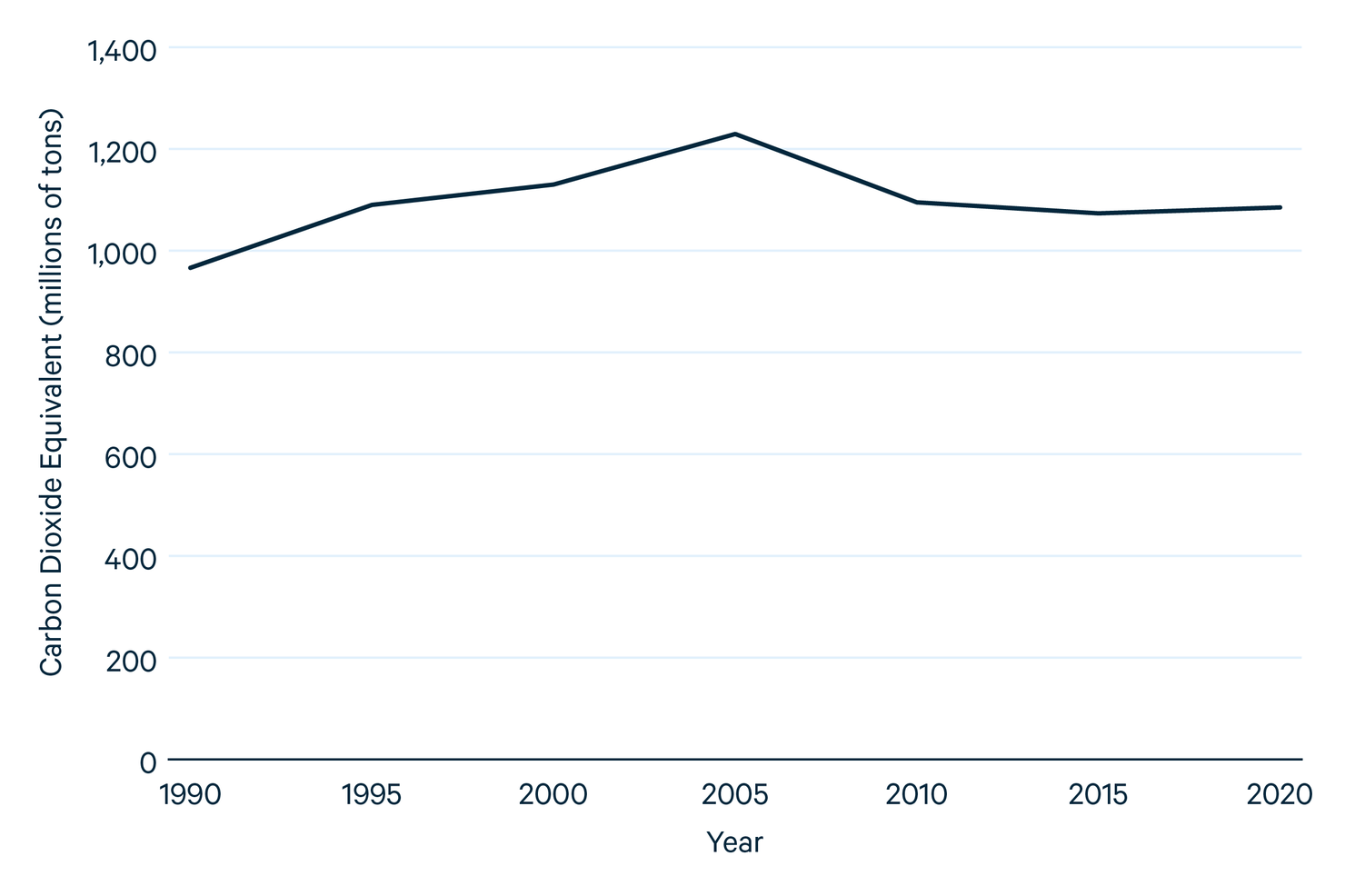

Figure 2 shows total emissions from vehicles on the road from 1990 to 2020. During that time, stricter fuel economy standards resulted in a decline of the average emissions rates for new vehicles by about 18 percent. However, total emissions were essentially flat between 1995 and 2020 (Figure 2). This is because total emissions depend not only on the emissions rates of new vehicles, but also on how much people drive, the emissions rates of older vehicles that are still on the road, and the carbon content of gasoline (which has not changed much over the last decade). For example, during the 2010s, overall driving increased by about 10 percent, partly offsetting the improvements in new vehicle fuel economy.

Looking ahead, if driving continues to increase at its historical rate, then tightening new vehicle standards might not significantly reduce emissions. The COVID-19 pandemic has reduced driving quite substantially, but signs have been indicating that driving is back on the upswing: total driving in June 2021 was about the same as total driving in June 2019, for instance.

Figure 2. Carbon Dioxide Equivalent Emissions from Light-Duty Vehicles

Source: US Environmental Protection Agency, “US Transportation Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 1990–2019”

Besides a likely increase in driving, a second reason may explain why tightening new vehicle standards might only modestly reduce total light-duty vehicle emissions over the next five years: the legacy of older and higher-emitting gasoline-powered vehicles. The average vehicle on the road is about 13 years old, and older vehicles have higher emissions rates because they were subject to less ambitious greenhouse gas standards when they were manufactured. For example, vehicles nine years old in 2020 had emissions rates that were, on average, 17 percent higher when they were first sold than the emissions of new vehicles in 2020. Many of these vehicles will continue to remain on the road for years. Because the vehicle fleet turns over so slowly, tightening new vehicle standards has a small but persistent effect on total fleet emissions.

Another key element in the Biden administration’s goal of transitioning away from fossil fuels is the shift toward vehicle electrification through incentives for purchasing electric or fuel cell–powered vehicles. Many auto companies have reacted by making ambitious commitments around electric vehicles. For example, General Motors has publicly stated that it will no longer sell gasoline vehicles by 2035

So far, though, electric vehicle sales have grown slowly in the United States. Electric vehicles first began selling around 2010, and as of the 2020 model year, only about 2 percent of all new cars sold were electric (Figure 3). Even if sales of electric vehicles can increase to 8 percent by 2026—the target, based on the US Environmental Protection Agency’s analysis of the proposed vehicle standards from the Biden administration—electric vehicles will make up just a small share of all vehicles on the road. Emissions of gasoline vehicles will still be the dominant source of emissions from the fleet for years to come.

Figure 3. Composition of Passenger Vehicle Fuel Types by Age in 2020

Source: IHS Markit

The effects of the proposed tighter standards and additional electric vehicles sales are likely to have only modest effects on total fleet emissions in the short term, but their impacts will grow over time, as older and higher-emitting vehicles continue to be scrapped and replaced by newer and cleaner vehicles.

However, reducing emissions from the vehicle fleet is a complex endeavor. In addition to standards, other policies will be important to achieving climate targets. If driving continues to grow in the 2020s like it has in recent years, the standards will have an even smaller impact on emissions.

Policies to accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles are likely to be important in the next few years. On the same day that the Biden administration announced the new fuel economy standards, it also announced a goal that half of all new vehicles sold in 2030 should be plug-in hybrid, all-electric, or fuel cell. Just how the recently proposed standards will help meet that goal is a question we’ll examine more closely in an upcoming blog post.

This article also appears on the University of Maryland’s Transportation Economics and Policy Blog, which is supported in part by funding through the Maryland Transportation Institute.