Congress is considering spending billions to subsidize electric vehicle purchases, but RFF modeling shows that such a policy would barely impact emissions over the next decade.

The Biden administration has announced a target of halving greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2030 relative to 2005 levels, and Congress is considering how to help achieve that target. A major question permeating the debate has been whether the policies under consideration in Congress will be sufficient to achieve such ambitious climate goals.

Recent modeling at Resources for the Future (RFF) shows that Congress’s plan to spend billions on subsidizing electric vehicles (EVs) will have little to no effect on transportation sector emissions through 2030. The subsidies probably won’t affect EV sales for at least the next five years, either. Given the same budget, a plan that jointly subsidizes clean vehicles while taxing dirty vehicles would achieve a much higher EV market share and greater emissions reductions.

Before turning to EV subsidies, we’ll consider how much the Biden administration’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) could reduce emissions by setting GHG standards for passenger vehicles and allowing the Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) program to proceed. (ZEV programs, currently active in 12 states, effectively require manufacturers to attain specific market shares for plug-in vehicles.) The vehicle GHG standards and ZEV program policies are a natural place to start, because as long as the Biden administration stays within Clean Air Act boundaries, it will be able to set whichever standards it wants (within certain legal limits). This leeway with implementing policies contrasts with the situation in Congress, where moderate Democrats and Republicans will heavily influence policy.

The Biden administration’s EPA standards likely will be at least as ambitious as the Obama EPA standards, and to help us assess what Biden’s EPA standards could accomplish, let’s imagine a hypothetical world in which Donald Trump had won the 2020 election and successfully defended his policies in court. Trump’s main policies that affected GHG emissions in the transportation sector substantially weakened the federal fuel economy and GHG standards for light-duty vehicles; Trump’s policies also prevented California and other states from setting more ambitious fuel economy standards than the federal government and running ZEV programs.

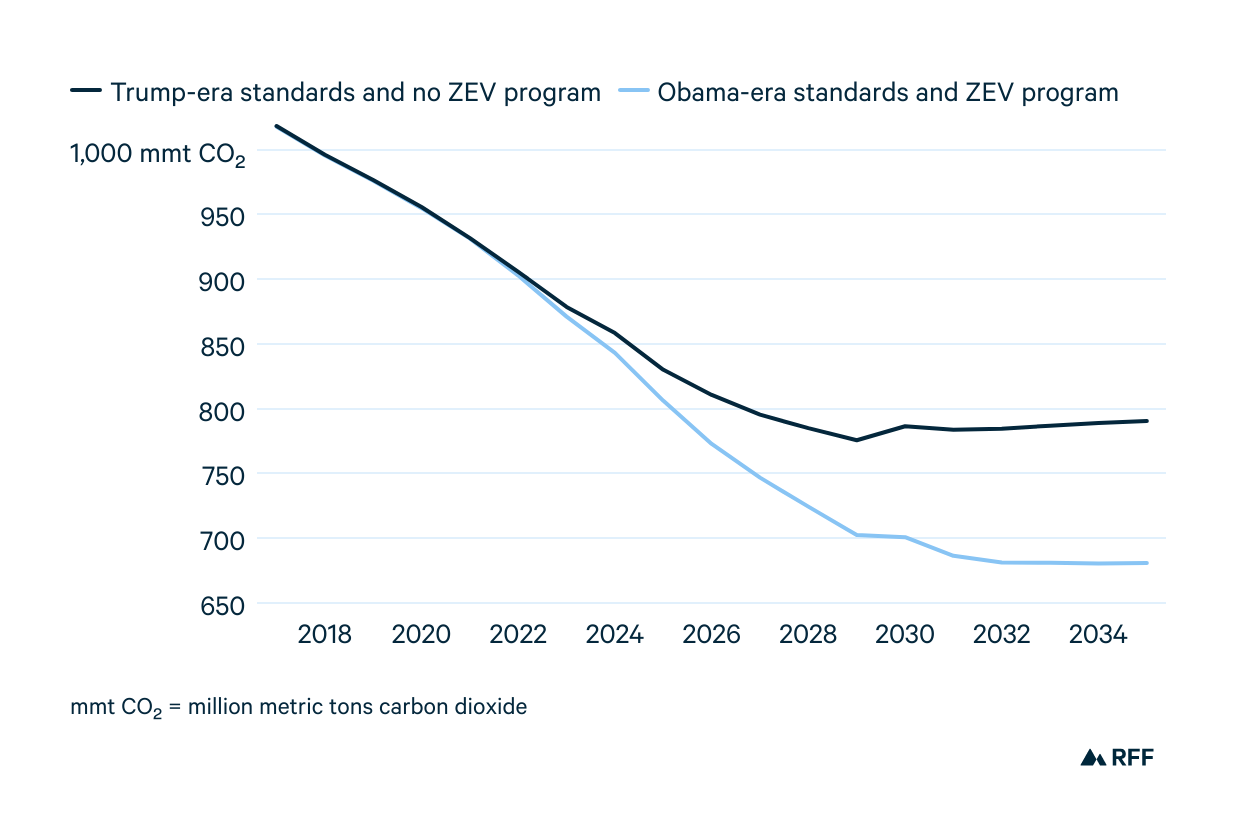

Returning to Obama-era standards and continuing the ZEV program would reduce emissions in 2035 by about 110 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, or 14 percent of light-duty vehicle GHG emissions compared to Trump administration policies (Figure 1). The estimates rely on the same economic model of light-duty vehicles that Joshua Linn has cited in a previous blog post, and which he developed alongside RFF University Fellow Benjamin Leard and HEC Montréal’s Katalin Springel.

Figure 1. On-Road Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Light-Duty Vehicles

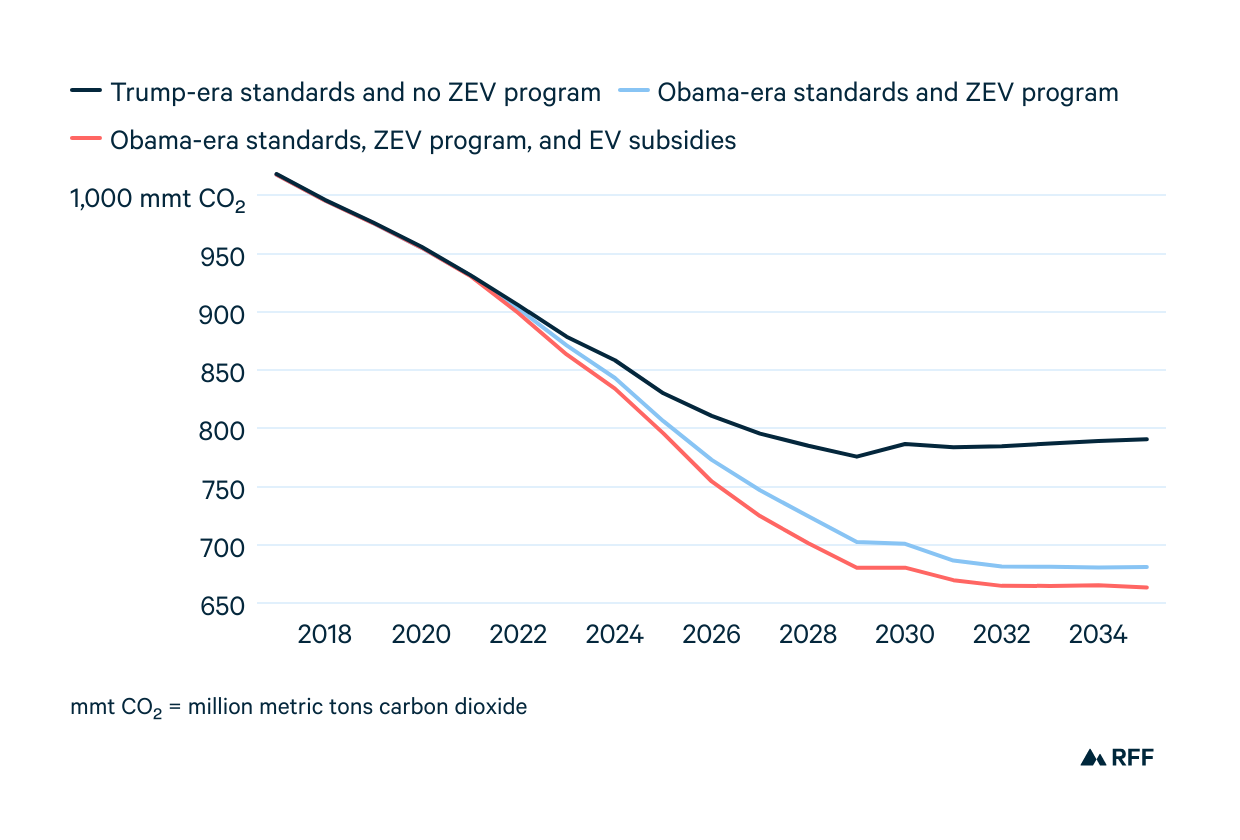

Turning to EV subsidies, we layer federal subsidies on top of the scenario that assumes Obama-era standards are in place. Under current law, subsidies phase out once a manufacturer sells 200,000 EVs; however, we consider the impacts of the subsidies if they were extended for all manufacturers through 2031. In this hypothetical scenario, all vehicles can receive the subsidy, regardless of the manufacturer’s total sales. We also assume that subsidies for EV charging stations would roughly double the number of stations from current levels over the next 10 years. These two additions reflect components of the Clean Energy for America Act, which recently passed the Senate Finance Committee.

These subsidies—totaling about $250 billion—barely affect emissions (Figure 2). This low impact on emissions is largely because of interactions between the subsidies and the standards. Manufacturers can meet the standards either by increasing the fuel economy of gasoline vehicles or by selling more EVs. As the subsidies increase the market share of EVs in non-ZEV states (since EV subsidies do not affect EV market shares in ZEV states), manufacturers don’t have to increase gasoline vehicle fuel economy as much. Compared to the scenario of Obama-era standards without subsidies, the scenario of Obama-era standards with subsidies increases the number of EVs and reduces the fuel economy of gasoline vehicles. Consequently, the overall effect on emissions is approximately zero. It’s not exactly zero, because by the early 2030s, the subsidies are big enough, battery costs have fallen far enough, and consumer demand has increased enough that the manufacturers just slightly exceed the federal GHG standards on average.

Figure 2. On-Road Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Light-Duty Vehicles, with EV Subsidies

If the subsidies won’t affect emissions and EV sales for at least several years, what might they accomplish? For ZEV states, which currently account for most EV sales, the subsidies shift the costs of the ZEV program to taxpayers and away from gasoline vehicle buyers and manufacturers.

For non-ZEV states, the subsidies would double the EV market share to about 10 percent by 2030. This increased market share would not significantly affect national emissions for the reasons stated above, but it could address other market failures associated with new technology. For example, the higher market shares could help the public learn more about clean vehicle technologies, possibly boosting consumer interest in EVs. In turn, higher consumer demand could help justify tighter EPA emissions standards for GHGs, but that’s a topic to explore in a future blog post.

Previous blog posts explain how subsidies for scrapping older vehicles and buying new EVs can be made more cost-effective by targeting the subsidies based on the emissions of other vehicles and the income of EV buyers. Putting aside the interactions between subsidies and other policies discussed above, targeting can help ensure that the subsidy dollars actually go toward cutting emissions.

Even more cost-effective than either of those ideas would be to combine the subsidies with taxes on dirty technologies. Although Congress is considering spending hundreds of billions of dollars on EV subsidies, the scope of the transportation sector’s climate problem is tremendous: Each year, about 17 million new cars are sold. If 10 percent of those are EVs (which just about matches the estimated market share in 2030), a subsidy of $7,000 per vehicle would cost $12 billion per year. Instead of offering a $7,000 subsidy for each EV, Congress could spend much less in total—but provide the same relative incentive to buy an EV—by jointly subsidizing EV purchases in the amount of $3,500 and taxing non-EV purchases $3,500. But if Congress decides to promote EVs using carrots (subsidies) without any sticks (taxes), success will depend on designing the subsidies in a way that really changes consumer choices, rather than giving checks to people who would have bought EVs, anyway.

This article also appears on the University of Maryland’s Transportation Economics and Policy Blog, which is supported in part by funding through the Maryland Transportation Institute.